My father always kept a cross in his pocket. Usually, it was the crucifix from a broken rosary. Or maybe it was a small plastic one, like the kind that Sister Ann Mary gave our third grade class at Our Lady of Sorrows. But no matter the kind, one could always be found in his pocket, along with the lint and the loose change and the lighter for his Pall Mall cigarettes. I remember once when I was a boy and asked him about it. His answer puzzled me. He said, “I need to be reminded who I am.” My father would leave it at that. He wasn’t much for preaching, lecturing or explaining. But it left me wondering, who was my father?

When I was a boy, I didn’t know much about my dad. I only knew that he was big and powerful and could throw a football the length of two backyards. He lorded over our household like a lion, drifting from couch to couch, sleeping when he was tired, eating when he was hungry and playing with us at his whim. At the time, what struck me most about my father was that he pretty much happily did whatever he pleased. This meant that when we went to the grocery store as a family, if he felt like opening a package of cookies before we got to the check out line, he did. If he felt like driving our family’s “Sunday car” during the week, (a Lincoln Continental), he did. And at two packs of Pall Mall a day, if he wanted to light up, no matter when or where, he did. My father was omnipotent. And to a boy, who so badly wanted to be a man, I needed to look no farther than to him. He was a quintessential man. A quintessential American. And as I would discover, a quintessential Christian.

Looking for a fight

My father was 5’11, 200 pounds with uncommonly fast hands. His favorite sport was boxing. And having grown up on 12th Street, just a stone’s throw away from the old Briggs Stadium in hardscrabble Detroit, he was pretty good at it too. He had always liked fighting because it was the way he proved himself. It validated him. Ironically, it was the fight that he never had that would change his life.

It was the Spring of 1961 and my father had just turned 21. But while most men of his generation were starting their careers, my father was still entrenched in the neighborhood where he grew up. It was predominantly Italian and Mexican though my father was neither. He was Maltese with a splash of Sicilian. But the neighborhood was also poor and it was Catholic, which he was both. As the story had it, on one particular night my father rolled into the Irish-American Club on Michigan Avenue looking for a fight. It was a place he had no business being. The micks who hung out at that place were from Holy Redeemer parish. The lads there may have dressed nicer than my father, but make no doubt, they liked to scrap as well. And they certainly weren’t welcoming of anyone from St. Vincent parish. Especially some guy looking for trouble, who looked like Sal Mineo in “Rebel Without a Cause.” My father could never recall who exactly he was looking for. Because the minute he walked into the place, he met somebody else. He met my mother.

He never fought again.

Faith and family

My mother didn’t change my father. But she did something more important. She gave him a reason to change. She gave him a reason to channel his need for validation into hard work. She gave him a reason to love and be compassionate. And most importantly, she gave him a reason to believe in God. My father would often point this out, saying that if it weren’t for my mother, he would’ve been just a another casualty of his neighborhood. My mother was everything good about being a Christian. She was effusively generous and kind to anyone who came into her orbit. While she never tried to to bring God to anyone, she tried to find God in everyone. And she usually did. My mother was Easter Sunday. And if one of the greatest things a man can do for his children is love their mother, then my father certainly did his job.

If my mother was Easter Sunday then my father was Good Friday. He was a dark brooder who not only understood pain and suffering – he seemed to embrace it. My father did everything hard and took no shortcuts. And though he became a very successful man, he never rewarded himself. He never took vacations. He never bought himself fine clothes. His comfort came from the joy of his kids, the love of his wife and the grace of his faith. Throw in a good prize-fight and Sinatra’s “Summer Wind” and he was in heaven.

An American success and life lessons

My father loved the water. He wasn’t the best of swimmers, and he never caught a fish in his life. But he loved the water as much as any sailor ever had. Maybe it was because his parents had grown up on an island. Or maybe it was because of what the water represented to them. My father was never close to his father. They never talked about things. But my father often cited him to me as inspiration. My father was proud that his father got on a boat to go to a place where he had never been and couldn’t speak the language. He had played clarinet in the Palermo symphony. And he moved to America to be a janitor at G.M. – just to make life better for my grandmother their children. My father ended up with a beautiful home on the body of water that his father crossed. Not bad for a kid from 12th Street.

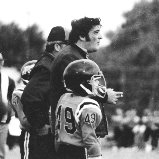

Most of what I learned from my father were not things that he told me, but rather things that I saw. He never drank. He never used a derisive word about anyone’s race, creed or color. And he always reached out to those in need. When coaching, (and this was important to him), he played all of his kids – whether it was required or not. My father was never pious or self-righteous. His list of friends included cops, priests, addicts and cons. And he treated them all the same—with love and respect.

But if I had one indelible image of my father when I was a boy, it was one of him during prayer. Prayer for a kid is always tough, especially for one like me who had the attention span of a moth. But watching my father pray was riveting. My father had been to places I had never been. And he had seen things that I would never see. But that man, that man who feared no one, would bow in silence and bury his head in his hands at church when he prayed. And even at my young age; an age when nothing was better than a sleepover at my buddy’s house; a time when I daydreamed of sports and when magic and adventure were around every corner, I thought to myself: Maybe he was on to something?

Finding my father again

For most of my life I thought my father was a very complicated man. I also had a sinking feeling that I was disappointing him. He wanted me so badly to be tough. In fact, before I was born he had lobbied hard for the name Rocco; a name that most assuredly would’ve changed my destiny. (I thank my mom eternally for winning that one.) My dad would’ve loved it if I had taken up boxing instead of football. Or had been a linebacker instead of a running back. Or faced fights instead of avoiding them. Truth is, I could’ve used a little more of my father when I was a boy. My little brothers would’ve been better protected. But in the end, I was too much like my mother. And for this, I think he loved me even more.

My father was an intense thinker and loved to play chess. But he also had a vesuvian temper that could end in explosive wrath. And while his mere presence could’ve instilled fear in just about anyone, he was a kind, affectionate man, whose generosity rivaled that of only my mother’s. Even though he sometimes seemed like a grenade that had its pin removed, he was my hero growing up.

My father died over ten years ago. Renal failure. In the end, his hands and feet had blackened from lack of circulation. But he would not allow amputation. Too much pride. He went out hard. Painful. Just like he liked it. But he also went out with his family surrounding him, in the bed where had lain with my mother, in a house he had built to be near his children and his grandchildren.

I still look for my father. I look for him when I am home alone. I look for him when I am at church. And I look for him when I am on the water. When I am there I often think, if my grandfather crossed the water for his family and my father built a home on the water for his family, what am I to do with the water for my family? Perhaps there is nothing. Perhaps, it is just there to remind me. Or perhaps I am looking in the wrong places, because I find my father elsewhere. I find him in a dear friend, a multi-Emmy winning writer, who I saw weep when his son left for college. I find him in another, who takes care of his son with cystinosis. I find him in my younger brothers, three wonderful fathers, who coach and play with their kids. And I sometimes find him in crowds, wherever a man lords over his family or is loving to the woman he is with. But mostly, I find him when I reach into my own pocket. There, with the lint and the loose change and keys to my car, is a cross. And there, I find my father.

Born in Detroit, P.G. Cuschieri is a writer who lives and works in Los Angeles. He is a grateful brother, uncle, friend and a proud Roman Catholic. He can be found on twitter.