Last week the Mormon missionaries stopped by looking for me. This hadn’t happened in awhile, but it’s not an unfamiliar experience. Five years ago I formally petitioned to have my name removed from the LDS Church’s membership records, and after that I didn’t hear from them for a while. But eventually the mail started coming again. And now there were these white-shirted 20-year-olds on my doorstep asking for me.

I invited them in. They declined, citing the “three man rule”. (They’re not supposed to be alone with women unless another man is on the premises.) So we stood awkwardly in the doorway while I explained that the reason they never saw me at church was that I had apostatized from the Mormon faith some years before, and was now a practicing Catholic.

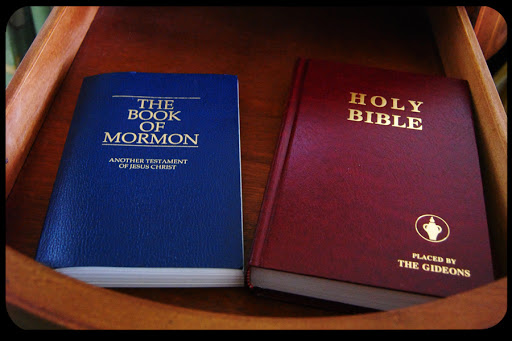

They asked why and I briefly explained. (I believe that Rome, not Salt Lake, is rock on which Christ’s Church is resting.) They challenged me to read the Book of Mormon and I cheerfully declined. (I’ve read it twice before, but now I have other reading priorities.) In their final go-for-broke play, they read me a three-verse passage from the Book of Mormon, and urged me to ask God directly about the truth of the Mormon faith. I gently explained that this would not be appropriate, because it isn’t a question that I have anymore. When God has already answered the deepest question of your heart, the correct response is to embrace the truth gratefully. It would just be churlish to keep pestering him about it.

After that I stood patiently and let them have the final word, accepted their phone number (on condition that they wouldn’t return unless I called it), and wished them a pleasant day.

My husband doesn’t understand why I bother talking to missionaries. He just says, “not interested” and closes the door, which is perfectly reasonable. It’s like hanging up on phone solicitors; if you’re not going to buy anything they’d probably rather save the time than listen to the pleasantries.

Still, with several generations’ worth of Mormon ancestors behind me, I feel that Mormons are “my people” in a kind of ethno-cultural sense. I can’t just slam the door on them, and if the local Mormon authorities want an account of me, I’m willing to give it. For all its flaws, Mormonism is the faith of my forefathers. But even beyond familial loyalty, I feel deeply grateful to the LDS Church for its incalculable contribution to my childhood and youth. Mormons taught me my Bible stories and gave me lots of no-nonsense straight talk about chastity. It’s hard to exaggerate the value of that in these confused times. Mormons also gave me a wonderful appreciation for what supportive, functional, family-oriented church communities can do. There’s a lot to be said for them and I would have been happy to stay, but for the inconvenient fact that I wasn’t a believer, and wasn’t willing to pretend.

I’m one of those cautious types who spent quite a number of years flitting on the outskirts of the Church before taking the plunge. Conversion itself, when I finally got around to it, wasn’t a particularly thrilling experience. Swimming the metaphorical Tiber was a lot like (I suspect) swimming the actual Tiber: I felt cold, muddy and rather alone. This is not so uncommon, I have found, among intellectual converts. We gobble the “good stuff” (theology, spirituality) in the safety of our bedrooms, and find that this sweet fruit has a pit in the middle. The intellectual journey is thrilling, but at the time of conversion itself, the unpleasant social components dominate the foreground. As my catechist recognized (he found me puzzling in the extreme), my original “Here I am, Lord,” was not offered with particular enthusiasm or delight.

Nine years later, though, I have to say that I love being a former Mormon. Talking to LDS missionaries, particularly in the week before Trinity Sunday, was a wonderful reminder of the reasons for that.

When Protestants become Catholic, they often experience the transition as a kind of completion. Protestantism lays a firm foundation, and Catholicism builds on top. One convert friend of mine (a former Protestant minister) describes her conversion as an “oh, there’s more!” sort of experience. Everything that seemed really important in her Protestant faith was part of Catholicism too, but the Church added more of the good stuff, from Sacraments to theology to scores of wonderful saints.

I had a different experience. Mormonism does not lay a firm theological foundation; quite the contrary. Actually I think the best way to understand it is as a Christian heresy, to be filed in the same category with Arianism, Nestorianism, Pelagianism and other distortions of Christian doctrine that have cropped up throughout Christian history. Rome has clarified that Mormon baptisms are not valid, meaning that individual Mormons are sacramentally akin to pagans and not properly termed “heretics”. But it’s obvious that Mormonism is overwhelmingly derived from Christianity, so merely repeating the “not Christian” line isn’t very illuminating in itself. Comparing the LDS Church to other historical heresies is a more helpful way of explaining what’s really going on with the Mormons.

Heresies tend follow a common pattern. Their founders try to update or simplify Christian doctrine by rejecting one or more of the core dogma that have held the Christian synthesis together over the centuries. The first step usually seems quite reasonable. Christian dogma is mysterious at several points, so the suggestion that it needs “upgrading” seems beguilingly plausible. It’s amazing, though, how quickly things crumble once a central pillar of the faith is jettisoned.

Mormons believe in a corporeal God. That is, God the Father has an actual body, as does Jesus Christ. They are distinct persons and distinct beings; the doctrine of the Trinity is rejected. From here Mormon theology cascades into some rather confused territory. Original sin is rejected. God himself is viewed as the product of moral maturation. Mere mortals are teased with the possibility that they themselves might attain godlike status.

To me, the moral is that Christian truth is a carefully balanced package. Time and again the Fathers had the choice to reject something complicated and strange in favor of something more obvious and digestible; time and again, they took the harder path. The wisdom of their choice becomes evident when it is juxtaposed against the trajectories of the many deviants who tried to “correct” Christian truth. They generally become confused in very short order, ending up in the dust bin of history, while the Church soldiers on into its third millennium.

The great thing about being a former heretic is that I really appreciate that repository of truth. It’s a wonderful thing to have such time-tested teachings, which provide a wonderful foundation for philosophical reflection, not to mention a fulfilled life. After talking to Mormon missionaries, I went to Trinity Sunday Mass, and actually found myself tearing up with gratitude as we sang: “Oh most holy Trinity! Undivided Unity! Holy God, Mighty God, God Immortal, be adored!”

I could not have sung those words in my Mormon childhood. I’m grateful for the chance to affirm them now.

Rachel Lu teaches philosophy at the University of St. Thomas and writes for Crisis Magazine and The Federalist. Follow her on Twitter at @rclu.