In his address to the Bishops at the conclusion of the Extraordinary Synod on the Family, Pope Francis identified and briefly described several temptations that the Church faces in her “journey” ahead for confronting the “many difficulties and innumerable [pastoral] challenges that families must confront; to give answers to the many discouragements that surround and suffocate families.”

At the heart of his address are several temptations. How should we think about these temptations? I would like to answer this question by drawing on an image used by the Evangelical Protestant, Francis Schaeffer (1912-1984) in a little book he wrote ("The Church Before the Watching World") some years back about “absolute limits beyond which a Christian cannot go and still stand in the historic stream of Christianity."

Schaeffer urges us to use the image of “a circle within which there is freedom to move.” The circle should be such that we will know when “we come to a place of danger.” In other words, he explains, “the edge of the circle” should be seen “as an absolute limit past which we ‘fall of the edge of the cliff’ and are no longer Christians at this particular point in our thinking.” Indeed, Schaeffer concludes, “Nothing, it seems to me, could be more valuable than to recognize some of the places where the ultimate borderline rests."

Now, I think Schaeffer’s image here is relevant in understanding the temptations Francis identifies and briefly describes because, or so it seems to me, he is trying to help us recognize “the places where the ultimate borderline rests.” Although he doesn’t spell out in detail what those absolute limits are, he does refer to them. For instance, “the fundamental truths of the Sacrament of marriage: the indissolubility, the unity, the faithfulness, the fruitfulness, that openness to life (cf. Cann. 1055, 1056; and Gaudium et spes, 48).”

Indeed, at the close of the address Francis describes in some detail with the help of predecessor Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI the nature, responsibility and limits of the papacy, emphasizing the servant form of this ministry.

“The Pope, in this context, is not the supreme lord but rather the supreme servant — the ‘servant of the servants of God’; the guarantor of the obedience and the conformity of the Church to the will of God, to the Gospel of Christ, and to the Tradition of the Church, putting aside every personal whim, despite being — by the will of Christ Himself — the ‘supreme pastor and Teacher of all the faithful’ (Can. 749) and despite enjoying ‘supreme, full, immediate, and universal ordinary power in the Church’ (cf. Cann. 331-334).” Here the pope is, arguably, assuring the whole Church that his “teaching office is not above the word of God, but serves it, teaching only what has been handed on, listening to it devoutly, guarding it scrupulously and explaining it faithfully in accord with a divine commission and with the help of the Holy Spirit” (Dei Verbum, §10).

Now, we might think that only those the pope calls “progressive and liberals” will fall off the edge of the cliff, but, no, Francis suggests that those whom he calls “traditionalists and [. . .] intellectuals” may do so as well. How so?

Traditionalists and Intellectuals

Consider the first temptation to “hostile inflexibility.” This temptation is not about holding on to the fundamental truths of the Catholic Faith, such as the pope identifies in his brief description of the Sacrament of Marriage. Of course the truths expressed in John Paul II’s 1981 Apostolic Exhortation, Familiaris Consortio are still universally valid. The temptation is, rather, about thinking that there is only one way to express or formulate in sentences those fundamental truths, and hence if one varies from those particular traditional formulations, he is ruled out as lacking in orthodoxy. I think we need to understand that Pope Francis is a man of Vatican II on this matter. He is following Pope John XXIII (who is following Vatican I, Dei filius, and the 5th century monk Vincent of Lérins, Commonitórium primum, 23) on this matter by presupposing that no one single formulation can exhaust the truths of the faith and hence he is implicitly drawing on a distinction between truth and its formulations that John made in a famous statement at the beginning of Vatican II: “The deposit or the truths of faith, contained in our sacred teaching, are one thing, while the mode in which they are enunciated, keeping the same meaning and the same judgment [eodem sensu eademque sententia], is another.” In short, truth is unchangeable, development of dogma is not a development of truth, but a development in the Church’s understanding of the truth.

Of course alternative expressions of the faith cannot all be true, meaningful, or in conformity with the fundamental truths of the Catholic faith expressed in prior articulations of Christian teaching. One way of knowing for sure that a formulation cannot be legitimate is when it occurs, as Gerhard Cardinal Müller has recently reminded us, “in a way that contradicts basic principles [of the teaching] [. . .] that would conclude or affirm the contrary."

The traditionalists, according to Pope Francis, are subject to this temptation. But not exclusively, however, since we can easily think of liberal Catholics that are completely deaf, so to speak, to the great writings of the last two popes — both their pre-papal and papal writings — in their efforts to provide during the last half a century a normative framework for interpreting the Second Vatican Council. I am sure that all of us have often heard the unjustified criticism that John Paul II and Benedict XVI are “restorationists,” wanting to undo the work of the council, and so on.

But why are intellectuals subject to the temptation of hostile inflexibility? What does Francis mean?

Looking at another temptation the pope identifies and describes will help us understand what he has in mind. “The temptation to neglect the ‘depositum fidei’ [the deposit of faith], not thinking of themselves as guardians but as owners or masters [of it].” Of course this is a temptation to which all of us are subject, ignoring that we are called to be servants of the Word of God. Yet, Francis has in mind that aspect of this temptation in which one ignores the inexhaustible richness of the truths of divine revelation, of ignoring that we see through a glass darkly (1 Cor 13:12), and that theology cannot live by merely repeating the formulations that were at one time expressed because no one formulation can exhaust the faith (fides quae creditor).

Furthermore, the pope continues describing this temptation, as the “temptation to neglect reality, making use of meticulous [technical] language and a language of smoothing to say so many things and to say nothing!” “Language of smoothing?” What does Francis mean? If we consider here that he is talking about those who are tempted to neglect reality, my best guess is that he is talking about internally coherent systems that smooth over the complexity and richness of reality. Unfortunately, the language that they use is technical, dense, and convoluted, which results in the obfuscation of reality rather than bringing reality to light. This is why the pope then refers to this view as “byzantinism,” meaning thereby attitudes that are inflexible or complicated.

Ideas and Reality

That this is what the pope has in mind with this temptation is clear if we turn to Evangelii gaudium (§231-232). We get a solid lead here as to what the pope means and why he lumps the intellectuals with the temptation to manifest a “hostile inflexibility.”

“There also exists a constant tension between ideas and realities. Realities simply are, whereas ideas are worked out. There has to be a continuous dialogue between the two, lest ideas become detached from realities. It is dangerous to dwell in the realm of words alone, of images and rhetoric. So a [. . .] principle comes into play: realities are greater than ideas. This calls for rejecting the various means of masking reality [. . . .] Ideas—conceptual elaborations—are at the service of communication, understanding, and praxis.”

Clearly, in connection with this temptation, the pope has in mind here a self-enclosed system of thought that uses many words, says many things, but really says nothing about reality. Hence, Francis is calling us to maintain a measure of self-critical independence vis-à-vis conceptual formulations of reality, so as to encourage an ongoing dialogue between the truth about reality and the way in which we formulate that truth. A good example of this dialogue is, arguably, John Paul II’s attempt to deepen our understanding of the Church’s teaching on sexual morality and marriage/family in works like "Love and Responsibility" and "Man and Woman He Created Them: A Theology of the Body."

Progressives and Liberals

Let me move on now to the other temptations, those that he sees “progressives and liberals” particularly facing. “The temptation to a destructive tendency to goodness.” We’re already stuck here, but not to worry. Here the Italian is “buonismo.” Apparently, this means something like “going along to get along,” and “not to make waves.”

This temptation, says the pope, occurs “in the name of a deceptive mercy [that] binds the wounds without first curing them and treating them; that treats the symptoms and not the causes and the roots. It is the temptation of the ‘do-gooders’, of the fearful, and also of the so-called ‘progressives and liberals’.”

An important example of what the pope has in mind when he speaks of a “deceptive mercy” is found in current confusion surrounding the meaning of being a church that is open, welcoming, inviting, proclaiming the inclusive message of the gospel. The mercy is deceptive because — as Walter Cardinal Kasper puts it in his book on Mercy, 162 — “Mercy without truth would be a consolation that lacks authenticity; it would be a mere empty promise and, ultimately, empty prattle [chatter].” The mercy is deceptive when it binds the wounds but doesn’t cure them or treat them, treating the symptoms but not the causes and roots of what ails us.

The pope’s thought is not subject to that confusion. He says, “The Church has the doors wide open to receive the needy, the penitent, and not only the just or those who believe they are perfect!” This point alludes to Luke 5:32: “I have not come to call the righteous, but sinners to repentance.” Francis continues: "The Lord has entrusted to them [pastors of the Church], and to seek to welcome — with fatherly care and mercy, and without false fears — the lost sheep." He adds, “I said welcome: rather to go out and find them.” This point alludes to the Parable of the Lost Sheep, Luke 15:1-7. In short, these thoughts strike me as deeply biblical and evangelical.

But what do we say to those who aver that the Church’s exclusiveness is contrary to the open, inviting, and inclusive message of the gospel?

In response to this charge, two things must be said. First, of course, no sinner is excluded from the Church — not the thief, murderer, adulterer, spouse abuser, and so forth. For it is proof of God’s own love for us that Christ died for us while we were still sinners (Rom 5:8; Eph 2:4-5). The Church is a body of sinners, and thus it makes absolutely no sense to claim that she excludes anyone, regardless of their sins. Listen to what these words about coming to Christ just as I am from the famous hymn, “Just as I am.”

Just as I am, without one plea, but that thy blood was shed for me, and that thou bidst me come to thee, O Lamb of God, I come, I come. Just as I am, and waiting not to rid my soul of one dark blot, to thee whose blood can cleanse each spot, O Lamb of God, I come, I come. Just as I am, thy love unknown hath broken every barrier down; now, to be thine, yea thine alone, O Lamb of God, I come, I come.

As the late Benedict Ashley, OP, notes, “[S]inners are not excluded from the Church’s care, since it prays for them and, like Jesus, seeks the lost sheep’s return (Luke 15:1-7; cf. St. Paul, 2 Cor 2:1-4 urging love for an excommunicated man).” Ashley adds, “The Church is always ready to receive them into full forgiveness and communion when they are willing to return to the Christian life. The Church is obliged to do this by Jesus’ own words about the love to be shown even to enemies (Matt 5:43-48) and the prodigal son (Luke 15:11-32). In this light, we should understand the welcoming nature of the Church of Christ, the Catholic Church.

Welcoming Church?

And yet, that is not what some people mean when they call on the church to be a welcoming church. They don’t distinguish the biblical sense of welcome from the sense of approving of them just as they are. In this connection, I think we face another temptation the pope identifies and describes: “The temptation to come down off the Cross, to please the people, and not stay there, in order to fulfill the will of the Father; to bow down to a worldly spirit instead of purifying it and bending it to the Spirit of God.”

I, for one, can see here the temptation that is expressed by the core doctrine of theological liberalism and which was expressed unsurpassably well by H. Richard Niebuhr. “A God without wrath brought men without sin into a Kingdom without judgment through the ministrations of a Christ without a Cross.”

But we stand condemned as sinners apart from the saving grace of Christ on the cross (Rom 8:1), and so we are called to make a heartfelt act of repentance in responding affirmatively to the invitation of the gospel of salvation. Sometimes I think that people who claim that they are being excluded from the Church deny this basic truth of the Christian faith. They seem to be suggesting that our human nature is pleasing to God and affirmed by him as it is, without redemption and renewal. But that would deny created reality’s fallen state, which would, as Fr. Thomas Guarino succinctly puts it, “overlook God’s judgment on the world rendered dramatically in the cross of Christ.”

In other words, those who succumb to the temptation the pope describes seem to deny the atoning work of God — the cross of Jesus Christ and sanctification by the Holy Spirit alone render life pleasing to God. To quote Fr. Ashely again: “The Church does not exclude homosexuals but seeks to help them live in a way that she is convinced will be for their real happiness, rather than to be a facilitator of their denial of their problem. Thus the Church excludes no one from her care; but care, to be genuine, must be based on truth not on making people comfortable.”

Cheap Grace

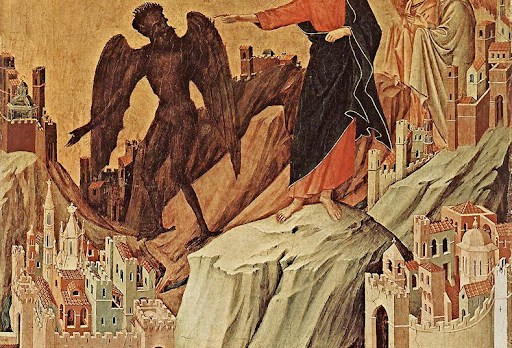

One last temptation is twofold: “The temptation to transform stones into bread to break the long, heavy, and painful fast.” Pope Francis refers us here to the Gospel of Luke (4:1-4) that recounts Christ’s temptations in the desert, particularly the temptation when Jesus is hungry and the Devil tempts by urging him to command “stone to become bread.”

If Jesus had taken the Devil’s option, it would have been the easy way out. This is what is called cheap grace. Dietrich Bonhoeffer gives us what is now a famous description of “cheap grace": “Let the Christian rest content with his worldliness and with this renunciation of any higher standard than the world.” Bonhoeffer adds, cheap grace is “the grace which amounts to the justification of sin without the justification of the repentant sinner who departs from sin and from whom sin departs. Cheap grace is not the kind of forgiveness of sin which frees us from the toils of sin. Cheap grace is the grace we bestow on ourselves. . . . Cheap grace is grace without discipleship, grace without the cross, grace without Jesus Christ, living and incarnate” (Cost of Discipleship, 36).

Truth without Mercy

There is a flip-side to this temptation, namely, “the temptation to transform bread into a stone and cast it against sinners, the weak, and the sick (cf Jn 8:7), that is, to transform it into unbearable burdens (Lk 11:46).” As Cardinal Kasper put is, “truth without mercy would be cold, dismissive, and hurtful. We cannot proclaim the truth according to the motto ‘sink or swim’” (Mercy, 162). Here, too, I overhear a deeply biblical injunction. St. Paul’s pastoral admonition is the pope’s own: “Brothers, if anyone is caught in any transgression, you who are spiritual should restore him in a spirit of gentleness” (Gal 6:1). In this context, we read in John Paul II’s 1993 Encyclical Letter, Veritatis Splendor, “appropriate allowance is made both for God’s mercy towards the sin of the man who experiences conversion and for the understanding of human weakness” (§104).

Yet, notwithstanding this call to compassion, John Paul explains, “Such understanding never means compromising and falsifying the standard of good and evil in order to adapt it to particular circumstances.” Therefore, he adds, “It is quite human for the sinner to acknowledge his weakness and to ask mercy for his failing; [but] what is unacceptable is the attitude of one who makes his own weakness the criterion of the truth about the good, so that he can feel self-justified, without even the need to have recourse to God and his mercy” (§95). Clearly, Pope Francis covers both these aspects in this description of the temptation.

All these temptations when properly understood — and this article is an attempt to do just that — help us to recognize the places where absolute limits rest.

I conclude with Francis’s prayer imploring the Lord to accompany the Church, guiding us in this journey for glory of His Name.

Eduardo Echeverria is Professor of Philosophy and Systematic Theology at Sacred Heart Major Seminary in Detroit. He earned his doctorate in philosophy from the Free University in Amsterdam and his S.T.L. from the University of St. Thomas Aquinas (Angelicum) in Rome.