Religious minorities have been targeted in Libya since 2012

The beheading of 21 Coptic Egyptians in Libya has stirred widespread international condemnation, yet this can neither be interpreted as a separate incident of ISIS’ brutality nor can it be seen exclusively in geo-political terms as a political manoeuvre in a power struggle between regional actors. This is part of a broader political project of cleansing the Middle East of its religious minorities in Muslim majority contexts, a project whose orchestrators are a dense network of actors of whom ISIS is only one player, and an outreach whose boundaries stretch well beyond Libya.

Islamist targeting of Christians in Libya since 2012

While ISIS has claimed responsibility for the beheading of the 21 Copts, in effect, the targeting of Copts is part of a more systematic targeting of Christians in Libya since 2012 which corresponds to the rise of Islamist militant groups taking over of large parts of the country. The assault on civil liberties by the militant Islamist groups has affected large populations, but Christians are specifically targeted on religious grounds associated with an ideology that sees them as infidels.

While there is a small indigenous Christian community who has lived there for hundreds of years, a small congregation of Catholics and a number of Protestant churches, the great majority of Christians in Libya are Coptic Orthodox Christians (estimated to be around 300,000) who came from neighboring Egypt in search of work or any kind of livelihood. During Gaddafi’s tenure, Coptic Christians established their own churches in Libya, worshipped without major inhibitions, and enjoyed relations with the majority Muslim Libyan population that were by and large convivial and harmonious. Many middle class families went to Libya in search of better economic opportunities, settled there, and used to visit Egypt every so often. The bulk of the Christian residents, however, are young men from poor, rural communities situated in some of the most deprived and excluded parts of Upper Egypt. They have crossed the borders to Libya in search of any employment they could find: as day laborers for the land-owning Libyans, as street vendors in the local markets, or any other job they could scavenge to save a little money and send to their families back home. They have been systematically targeted by various militant groups in Libya, including the Battalion of Ansar Al Shariah, Al Nusra and a cocktail of jihadi groups.

Though there is widespread chaos in Libya and terrorist attacks have spared no one, the assaults on Christians since December 2012 have been systematic. Churches have been burnt, ransoms imposed, and individuals tortured and killed. Christians would be recognized by the tattoo of a cross imprinted on their wrist or arm. In other incidents, Muslim local informants would relay to Islamist groups the names and addresses of Christians in their community, and individuals acting on economic predatory grounds would report where Christians were to Islamist groups in return for a reward.

Why did the Christians not return to Egypt in view of these alarm bells? Some were actually captured on their way back to Egypt, fleeing Libya. Others thought that if they went into hiding, they would be safer, while still others waited for the situation to calm down, knowing they had no alternative source of livelihood to go to back home to.

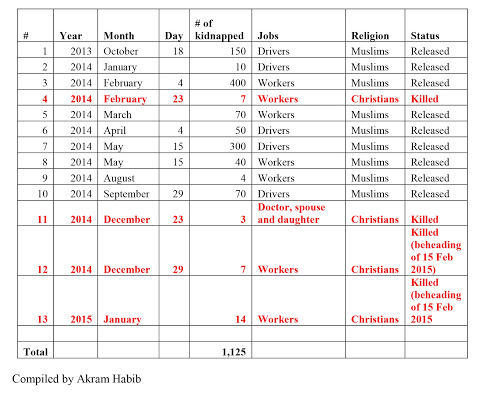

Large scale kidnappings, selective killings

Since October 2013 up to the present, there have been 1,125 incidents of Egyptians being kidnapped in Libya. The majority are poor, marginalized young people in search of a livelihood. Of the 1, 125 kidnapped, none of the Muslim men were killed and were all released. Of the Christians captured, all have been killed. (though there may be more who were taken hostages, the whereabouts of which are unknown, and undocumented in the media). This cross-comparison of the predicament of the Egyptians who were captured suggests that there is a pre-orchestrated plan of eliminating those who happen to be Copts on grounds of religion.

The killing of the Copts and the release of the others is only explained by the will of the assailants. The BBC, for example, reports that eyewitness accounts in one incident of kidnapping involved an armed group dashing into a house full of Egyptian workers, asking whether there were any Christians there, seizing them, and leaving the rest.

Beyond Libya: Islamists’ systematic targeting of religious minorities in the Middle East

The cleansing of Libya of its Christian population is part of a broader political project of political Islamist groups to rid the world of religious pluralism. Again, it cannot be reiterated enough that this political project seeks to redraw the profile of its political community in a way that is exclusionary of women, artists, human rights activists, those who interpret/practice the faith differently, and the list goes on.

However, there is a striking similarity in the Islamists’ modalities of targeting religious minorities across the borders, whether in Iraq, Syria, Libya or other parts of the region.

The targeting relies on the collaboration of various Islamist networks on scanning the horizons for where Christians live and work. It also relies on local informants sharing the profile of families in great detail and often (though not always) benefitting economically from such transactions. The targeting involves Islamist militants’ enforcement of a ransom in return for securing the right to live; kidnappings targeting Christians in Iraq, which have been happening since the American Occupation of Iraq; and the disintegration of the Iraqi state into sectarian silos. What ISIS brought to Iraq and Syria, however, is a form of religious cleansing of an intensity and scale that has prompted Amnesty International to attest that fresh evidence it uncovered “indicates that members of the armed group calling itself the Islamic State (IS) have launched a systematic campaign of ethnic cleansing in northern Iraq, carrying out war crimes, including mass summary killings and abductions, against ethnic and religious minorities.”

A recently released UN report produced by the U.N. body responsible for reviewing Iraq’s record for the first time since 1998 denounced “the systematic killing of children belonging to religious and ethnic minorities by the so-called ISIL, including several cases of mass executions of boys, as well as reports of beheadings, crucifixions of children and burying children alive.”

There are communities now facing an existential threat. We recognize that this political project is neither encapsulated in ISIS nor contained in the Libyan boundaries because the beheading is only the tip.

Mariz Tadros

is a fellow at the Institute of Development Studies, Sussex University. She studies the politics and human development of the Middle East. This article was originally published on Arc of the Universe, the blog of the Center for Civil and Human Rights at the University of Notre Dame.