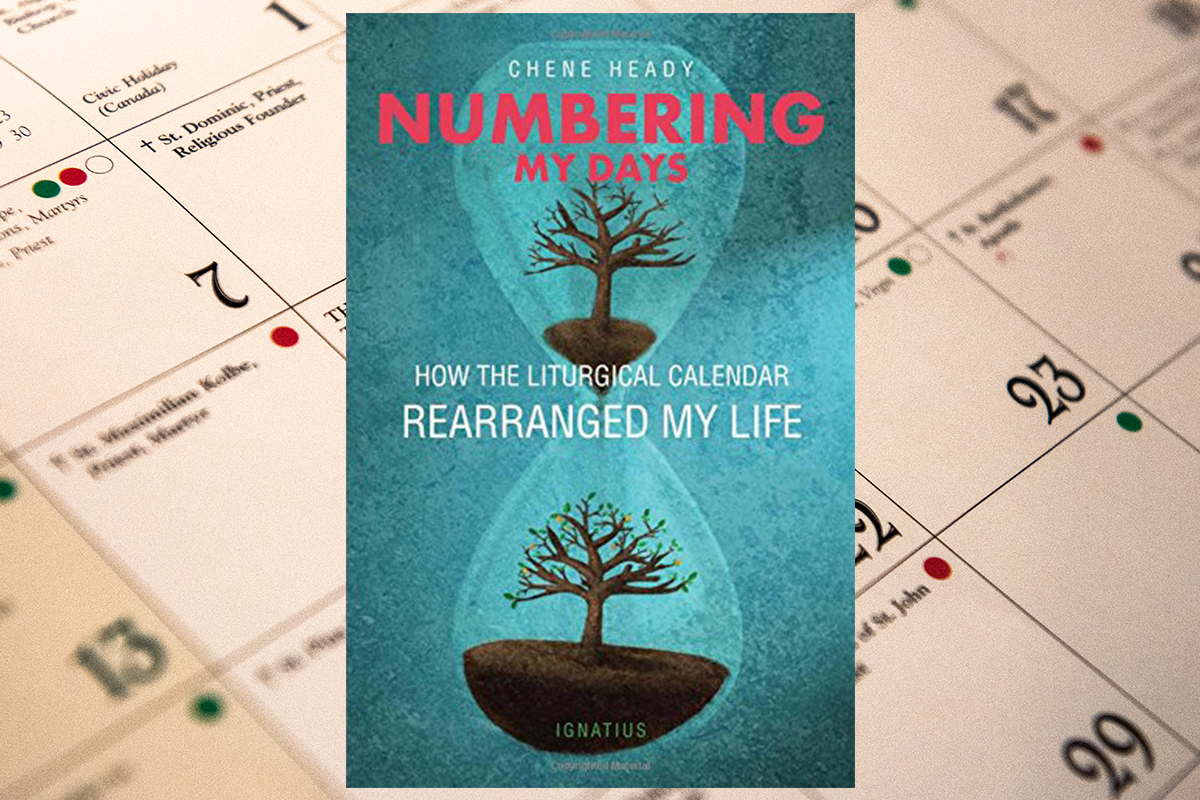

Try living on God’s timetable — you see the world in a whole new wayAdvent. Christmas. Ordinary Time. Lent. If you’re a cradle Catholic, perhaps it all can become ordinary after a time, background music to busy Sundays. But if you are a church-goer, you have this schedule to the year that can help rearrange and even transform your life. And Chene Heady, in a book called Numbering My Days: How the Liturgical Calendar Rearranged My Life, wants to help. Heady, who teaches in the English Department at Longwood University in Virginia, shares some of his own experience.

Kathryn Jean Lopez: How is the liturgy “our universal story”? What does that mean practically?

Chene Heady: Many sociologists and intellectual historians have suggested that the distinguishing hallmark of the modern West is the loss of a sense of shared meaning. In literary terms, we have lost our sense of story. Human experience strikes moderns (including, at times, me) as a random, indeterminate sequence of events without meaningful shape, and our lives are correspondingly rendered in the discontinuous, fragmentary shouts of Facebook and Twitter. History has no overall trajectory and the world cannot be rendered in terms that make any human sense.

But the Church, which is older and larger than the modern West, offers an alternate perspective. Christianity teaches that the universe does have an overall story, running from creation until the end of time, and that this story can be embodied in the life of a concrete individual: Jesus. The liturgical calendar, which is structured primarily around the life of Christ and secondarily around the lives of his followers the saints, serves to connect our daily lives to this story. In practical terms, I’m going to see the world differently depending on whether today (January 25) is the Conversion of St. Paul, and hence a challenge to interior conversion, or simply Wednesday.

Lopez: Is living the liturgical year realistic with marriage and kids and schedules and jobs and no time?

Heady: Actually, I wrote my book to show that living the liturgical year is possible (and beneficial) for someone as overstretched, distracted, and spiritually average as me. As the book opens, I am in a coffee shop with my daughter, passing her bits of croissant and encouraging her to sing “Old McDonald” so she doesn’t distract me while I guzzle coffee and knock out work for my job. Not my proudest moment. But many readers have told me that this scene describes their lives exactly. If the liturgical year is our universal story, then it’s for all of us at all times—even when we feel we have no time.

Lopez: So how do you start the work of numbering days?

Heady: Many of us live lives structured around the meeting requests on our office calendar and the messages cluttering our e-mail in-boxes. These constant demands make taking on a new spiritual practice seem impossible. If you live this sort of life, I would recommend that you sign up to receive the liturgical readings of the day via e-mail from the USCCB. You can make liturgical reflection part of your life by incorporating it into the habits you already have. It takes about 10 minutes to read and think about the scriptures for the day from the lectionary (writing about them, as I did, obviously takes a bit longer); the time commitment can, if necessary, be quite marginal.

Lopez: How can it rearrange life?

Heady: The lectionary readings for each day can rearrange your life when you treat them not as antique curiosities but as an interpretive key for the day ahead. I made a conscious decision to act as if the liturgical calendar, more than the clock, were the organic unit of time. I reasoned that since God guides the Church and God is the author of time, I was encountering these readings not coincidentally but exactly when I needed to hear them. To make this shift in perspective and chart its results is to number one’s days. St. Francis of Assisi is the perfect example. He took the Gospel reading for the day—“Sell whatsoever thou hast and give to the poor” (Mk. 10:21)—as a personal injunction, and we all know what happened next. My own transformations were less dramatic—as the infomercials disclaim, “results may vary”—but still quite real. I suspect that any attempt to juxtapose the liturgical calendar and one’s daily life would challenge one’s priorities somewhat and lead to a somewhat altered life.

Lopez: You call it entering into “divine time.” What do you say to anyone for whom this is sounding so otherworldly, so mystical, so impractical?

Heady: I’m not particularly mystical myself. As a teenager I read a bunch of St. Francis of Assisi and Gerard Manley Hopkins and decided that I would go out in the woods and mystically commune with God in nature. I had an asthma attack and immediately ran back inside, which basically sums up my track record on mysticism.

Practicing the liturgical calendar is eminently practical. People are social creatures, and our social environment shapes how we experience time. As I have mentioned, most of us spend our weekdays centered around work (production) and our weekends centered around leisure (consumption). If we see ourselves “as producers and consumers rather than as divine creations,” we do so in part because this is how we structure our time; our internal clocks beat to the measure of this particular social order.

So, if we set mysticism entirely aside, time still inevitably has a larger, social meaning for us. We have no choice about that. But we all belong to multiple social worlds and we can to some degree determine which of these will most fully structure our time and shape our experience. We can decide whether our lives will be shaped by the liturgical calendar or merely the office calendar, by the story of Christ and the saints or simply the series of tasks we have to perform. Even in purely psychological terms, it should be obvious which method of experiencing time is likely to lead to a healthier and deeper life.

Lopez: What do you do with Ordinary Time?

Heady: Many Catholics wonder what to make of Ordinary Time, which is so long and can seem so dull. But the idea of the liturgical calendar as a whole is that every day possesses divine meaning. The unremarkable weeks of Ordinary Time, as surely as Advent and Lent, serve to connect the insights of scripture to our daily experience. Many of the scriptural texts for Ordinary Time—especially those from St. Paul—explicitly ruminate on the challenges we face on the long march of ordinary days that makes up so much of our year, or in the marathon that makes up our life. Ordinary Time challenged me to look for graced meaning in the most quotidian, trivial, and even tedious moments of my life. I tried to be attentive to presence of meaning in the mundane, rather than (as I would have previously) simply zoning out after Pentecost.

Lopez: What has this numbering the days approach to life done for your knowledge of Scripture? Relationship with Christ?

Heady: St. Jerome suggested that we know Christ through knowing the Scriptures, so these questions are connected. I am a rather hyperactive, frantic person, and this approach to life taught me for the first time the rudiments of what spiritual writers call “recollection.” The “one thing needful,” Jesus says, isn’t any particular activity; it is to stop and listen to him (Lk. 10:42). I now try to pause for at least a moment before speaking or acting to ask myself what light the liturgical readings for the day might shed on my situation. And this tiny bit of recollection affected how I spoke and acted when, for instance, I couldn’t fix a dripping shower head, or the next-door neighbor dumped a third dead car in her yard, or my daughter coughed a raisin out of her nose, or a local college student told us about her upcoming eviction. Christ has been with me in moments both profound and ordinary.