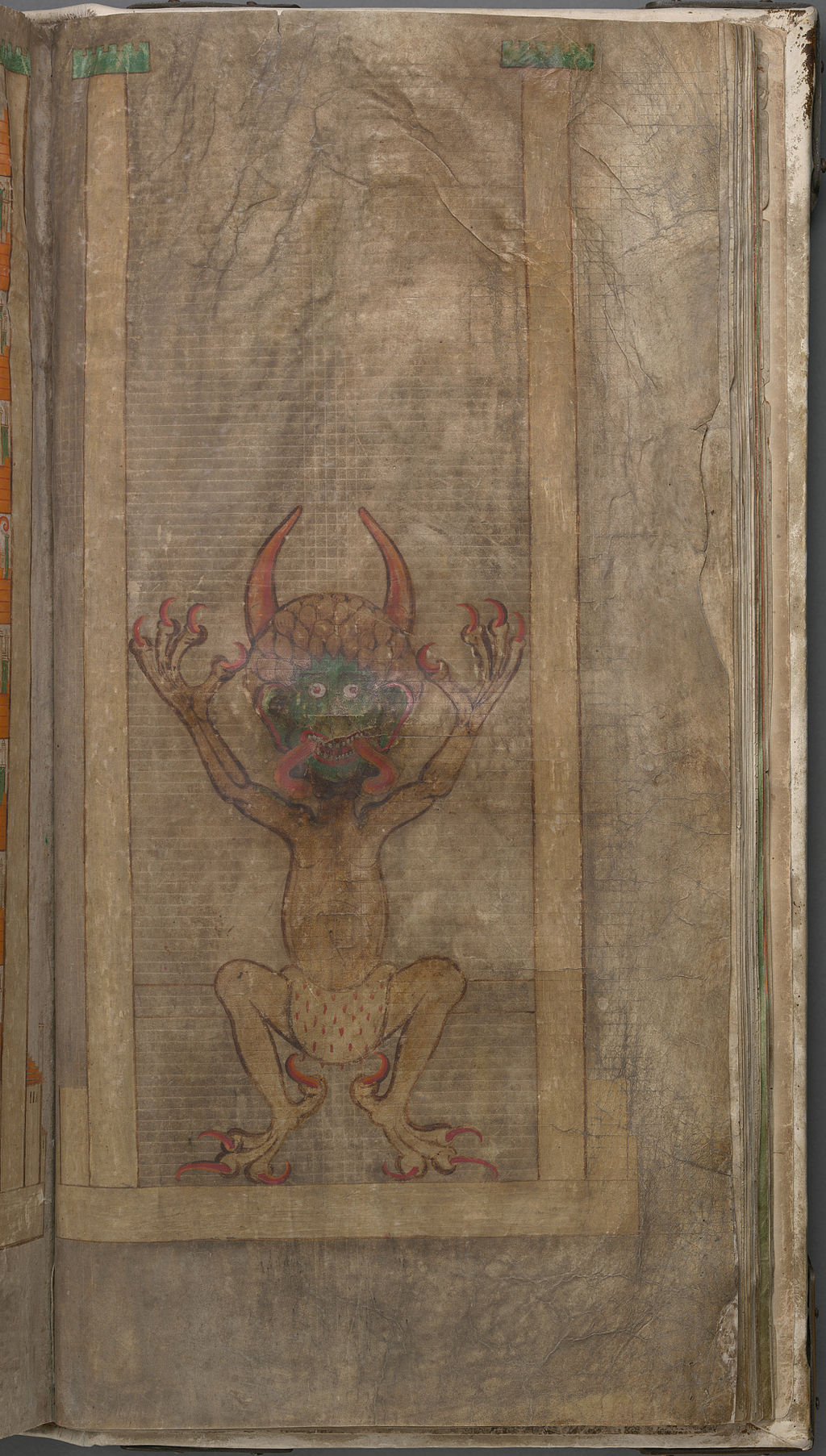

Did the illustration of Satan on the book’s cover inspire this strange tale?

Lenten Campaign 2025

This content is free of charge, as are all our articles.

Support us with a donation that is tax-deductible and enable us to continue to reach millions of readers.

A Benedictine monk living in the monastery of Podlažice was sentenced to be walled up alive after breaking his vows, the legend goes. In a desperate attempt to avoid his punishment, he promised he would create, in a single night, a book that would include all human knowledge. The abbot, out of mercy, couldn’t but accept the man’s proposal. But near midnight, the monk realized he could not complete the task alone, so asked the devil to him to help him finish the book, in exchange for his soul. The devil completed the manuscript and the monk added an image of the fallen angel in the book, allegedly out of gratitude for his aid.

Of course, this is only a legend. Several tests have revealed that the calligraphy alone – not taking into account the illustrations and other embellishments of the manuscripts — might have taken at least five years of non-stop writing. The so-called “Devil’s Bible” is actually the famous Codex Gigas (Latin for “Giant Book”), probably dating to the 13th century.

The name Gigas might be due either to its exceptionally large dimensions (it runs 620 pages and three-feet from the top of the spine to the bottom) or to the vast number of works collected in it. The Codex Gigas is much more than a Bible. It includes the Old Testament, the New Testament, an incomplete copy of the Vulgate, the Chronica Boemorum of Cosmas of Prague, two works of the Jewish historian Flavius Josephus, the Etymologies of St. Isidore of Seville, instructions concerning exorcisms, some medical treatises of Constantine the African, the Rule of St. Benedict, a calendar, a list of benefactors of the monastery, and a long list of “rarities” including scientific and alchemical sketches.

It should not surprise us that science and alchemy — which today we might think of as the opposing worldviews of reason and magic — are present side by side in a medieval religious work. At that time, scientific thought was deeply influenced by flawed translations of ancient philosophical works. A thin line separated the alchemist from the philosopher and the scientific researcher. The practice of alchemy, for instance, was not forbidden until 1317, in Pope John XXII’s bull Spondent Pariter.

The Codex Gigas is unarguably the largest book of the Middle Ages, and in its time was even considered to be one of the wonders of the world. The curious image of the devil on one of its pages is responsible for fueling the legend about the book’s origins, and gave rise to its nickname (that is, “the Devil’s Bible”). But in truth, the image has only been included in the text because, right on the next page, the reader finds an illustration of the City of God: the author was simply showing the opposition of good and evil, heaven and hell.

To browse through this magnificent book, click here, for the National Library of Sweden’s digitized version.