Capuchin priest, Fr. Raniero Cantalamessa, preaches Good Friday homily to Pope Francis

VATICAN CITY — This evening in Rome, Pope Francis celebrated the Good Friday liturgy of the Passion of the Lord in St. Peter’s Basilica.

During the liturgy, the Passion account from the Gospel of John was read. The preacher to the papal house followed by a homily preached by Fr. Raniero Cantalamesa, O.F.M., will then preach a homily to Pope Francis and all those present.

Here below we offer our readers the official English translation of Fr. Cantalamessa’s homily for Good Friday.

“O CRUX, AVE SPES UNICA”

The Cross, the Only Hope of the World

We have listened to the story of the Passion of Christ. Apparently nothing more than the account of a violent death, and news of violent deaths are rarely missing in any evening news. Even in recent days there were many of them, including those of 38 Christians Copts in Egypt killed on Palm Sunday. These kinds of reports follow each other at such speed that we forget one day those of the day before. Why then are we here to recall the death of a man who lived 2000 years ago? The reason is that this death has changed forever the very face of death and given it a new meaning. Let us meditate for a while on it.

“When they came to Jesus and saw that he was already dead, they did not break his legs. But one of the soldiers pierced his side with a spear, and at once there came out blood and water” (Jn 19:33- 34). At the beginning of his ministry, in response to those who asked him by what authority he chased the merchants from the temple, Jesus answered, “Destroy this temple, and in three days I will raise it up” (Jn 2:19). John comments on this occasion, “he spoke of the temple of his body” (Jn 2:21), and now the same Evangelist testifies that blood and water flowed from the side of this “destroyed” temple. It is a clear allusion to the prophecy in Ezekiel about a future temple of God, with water flowing from its side that was at first a stream and then a navigable river, and every form of life flourished around it (see Ezek 47:1ff).

But let us enter more deeply into the source of the “rivers of living water” (Jn 7:38) coming from the pierced heart of Christ. In Revelation the same disciple whom Jesus loved writes, “Between the throne and the four living creatures and among the elders, I saw a Lamb standing, as though it had been slain” (Rev 5:6). Slain, but standing, that is, pierced but resurrected and alive.

There exists now, within the Trinity and in the world, a human heart that beats not just metaphorically but physically. If Christ, in fact, has been raised from the dead, then his heart has also been raised from the dead; it is alive like the rest of his body, in a different dimension than before, a real dimension, even if it is mystical. If the Lamb is alive in heaven, “slain, but standing,” then his heart shares in that same state; it is a heart that is pierced but living—eternally pierced, precisely because he lives eternally.

There has been a phrase created to describe the depths of evil that can accumulate in the heart of humanity: “the heart of darkness.” After the sacrifice of Christ, more intense than the heart of darkness, a heart of light beats in the world. Christ, in fact, in ascending into heaven, did not abandon the earth, just as he did not abandon the Trinity in becoming incarnate.

An antiphon in the Liturgy of the Hours says, “the plan of the Father” is now fulfilled in “making Christ the heart of the world.” This explains the unshakeable Christian optimism that led a medieval mystic to exclaim that it is to be expected that “there should be sin; but all shall be well, and all shall be well, and all manner of thing [sic] shall be well” (Julian of Norwich).

* * *

The Carthusian monks have adopted a coat of arms that appears at the entrance to their monastery, in their official documents, and in other settings. It consists of a globe of the earth surmounted by a cross with writing around it that says, “Stat crux dum volvitur orbis” (“The Cross stands firm as the world turns”).

What does the cross represent in being this fixed point, this mainmast in the undulation of the world? It is the definitive and irreversible “no” of God to violence, injustice, hate, lies—to all that we call “evil,” and at the same it is equally the irreversible “yes” to love, truth, and goodness. “No” to sin, “yes” to the sinner. It is what Jesus practiced all his life and that he now definitively consecrates with his death.

The reason for this differentiation is clear: sinners are creatures of God and preserve their dignity, despite all their aberrations; that is not the case for sin; it is a spurious reality that is added on, the result of one’s passions and of the “the devil’s envy” (Wis 2:24). It is the same reason for which the Word, in becoming incarnate, assumed to himself everything human except for sin. The good thief to whom the dying Jesus promised paradise, is the living demonstration of all this. No one should give up hope; no one should say, like Cain, “My sin is too great to be forgiven” (see Gen 4:13).

The cross, then, does not “stand” against the world but for the world: to give meaning to all the suffering that has been, that is, and that will be in human history. Jesus says to Nicodemus, “God sent the Son into the world, not to condemn the world, but that the world might be saved through him” (Jn 3:17). The cross is the living proclamation that the final victory does not belong to the one who triumphs over others but to the one who triumphs over self; not to the one who causes suffering but to the one who is suffering.

* * *

“Dum volvitur orbis,” as the world turns. Human history has seen many transitions from one era to another; we speak about the stone age, the bronze age, the iron age, the imperial age, the atomic age, the electronic age. But today there is something new. The idea of a transition is no longer sufficient to describe our current situation. Alongside the idea of a change, one must also place the idea of a dissolution. It has been said that we are now living in a “liquid society.” There are no longer any fixed points, any undisputed values, any rock in the sea to which we can cling or with which we can collide. Everything is in flux.

The worst of the hypotheses the philosopher had foreseen as the effect of the death of God has come to pass, which the advent of the super-man was supposed to prevent but did not prevent: “What did we do when we loosened this earth from its sun? Whither does it now move? Whither do we move? Away from all suns? Do we not dash on unceasingly? Backwards, sideways, in all directions? Is there still an above and below? Do we not stray, as through infinite nothingness?” (Nietzsche, Gay Science, aphorism 125).

It has been said that “killing God is the most horrible of suicides,” and that is in part what we are seeing. It is not true that “where God is born, man dies” (Jean-Paul Sartre). Just the opposite is true: where God dies, man dies.

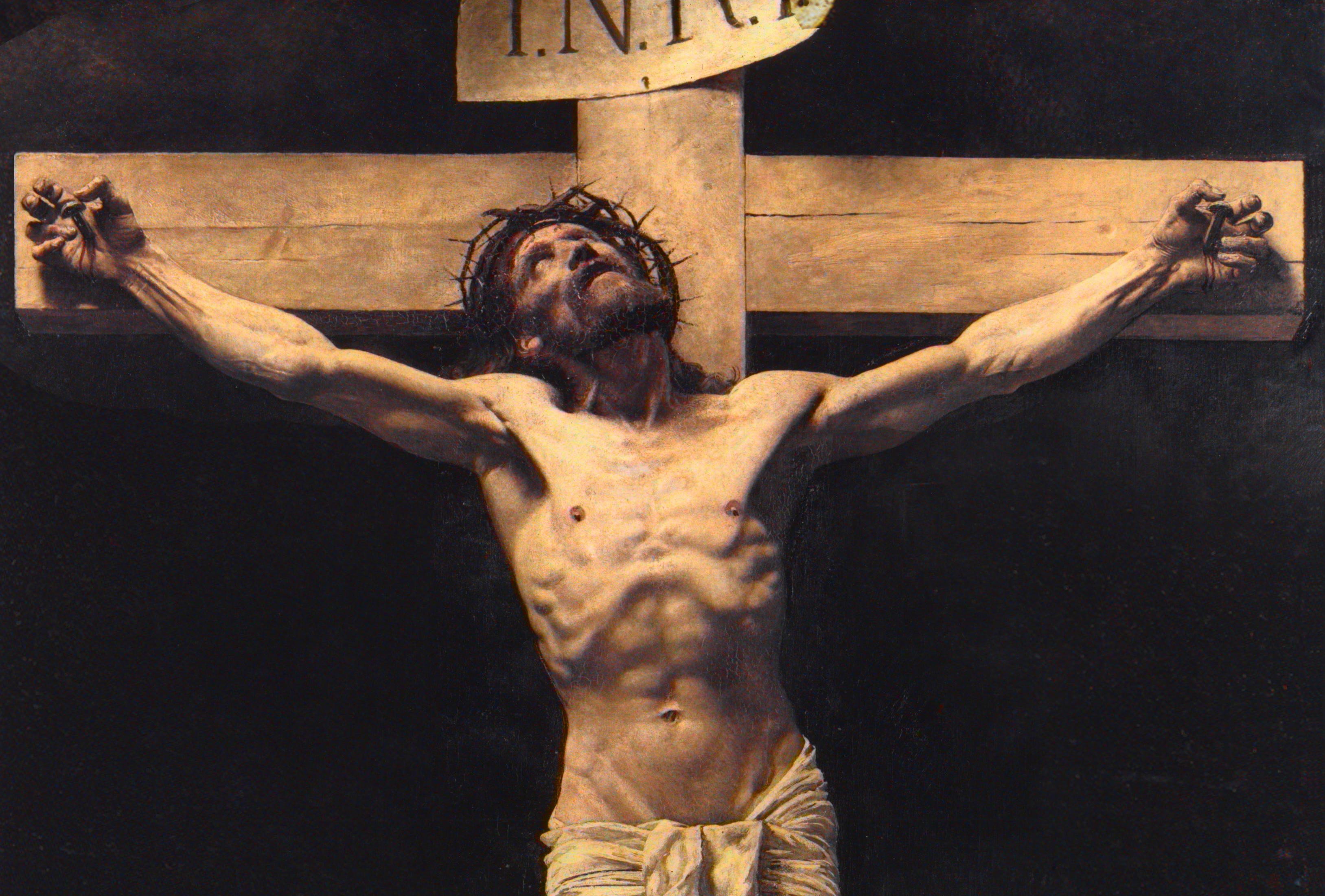

A surrealist artist from the second half of the last century (Salvador Dalí) painted a crucifix that seems to be a prophecy of this situation. It depicts an immense, cosmic cross with an equally immense Christ seen from above with his head tilted downward. Below him, however, is not land but water. The Crucified One is not suspended between heaven and earth but between heaven and the liquid element of the earth.

This tragic image (there is also in the background a cloud that could allude to an atomic cloud) nevertheless contains a consoling certainty: there is hope even for a liquid society like ours! There is hope because above it “the cross of Christ stands.” This is what the liturgy for Good Friday has us repeat every year with the words of the poet Venanzio Fortunato: “O crux, ave spes unica,” “Hail, O Cross, our only hope.”

Yes, God died, he died in his Son Christ Jesus; but he did not remain in the tomb, he was raised. “You crucified and killed Him,” Peter shouts to the crowd on the day of Pentecost, “But God raised him up” (see Act 2:23-24). He is the one who “died but is now alive for evermore” (see Rev 1:18). The cross does not “stand” motionless in the midst of the world’s upheavals as a reminder of a past event or a mere symbol; it is an ongoing reality that is living and operative.

* * *

We would make this liturgy of the Passion pointless, however, if we stopped, like the sociologists, at the analysis of the society in which we live. Christ did not come to explain things but to change human beings. The heart of darkness is not only that of some evil person hidden deep in the jungle, nor is it only that of the western society that produced it. It is in each one of us in varying degrees.

The Bible calls it a heart of stone: “I will take out of your flesh the heart of stone,” God says through the prophet Ezekiel, “and give you a heart of flesh” (Ez 36:26). A heart of stone is a heart that is closed to God’s will and to the suffering of brothers and sisters, a heart of someone who accumulates unlimited sums of money and remains indifferent to the desperation of the person who does not have a glass of water to give to his or her own child; it is also the heart of someone who lets himself or herself be completely dominated by impure passion and is ready to kill for that passion or to lead a double life. Not to keep our gaze turned only outward toward others, we can say that this also actually describes our hearts as ministers for God and as practicing Christians if we still live fundamentally “for ourselves” and not “for the Lord.”

It is written that at the moment of Christ’s death, “The curtain of the temple was torn in two, from top to bottom; and the earth shook, and the rocks were split; the tombs also were opened, and many bodies of the saints who had fallen asleep were raised” (Matt 27:51). These signs are generally given an apocalyptic explanation as if it is the symbolic language needed to describe the eschatological event. But these signs also have a parenetic significance: they indicate what should happen in the heart of a person who reads and meditates on the Passion of Christ. In a liturgy like today’s, St. Leo the Great said to the faithful, “The earth—our earthly nature—should tremble at the suffering of its Redeemer. The rocks—the hearts of unbelievers—should burst asunder. The dead, imprisoned in the tombs of their mortality, should come forth, the massive stones now ripped apart.” (“Sermon 66,” 3; PL 54, 366).

The heart of flesh, promised by God through the prophets, is now present in the world: it is the heart of Christ pierced on the cross, the heart we venerate as the “Sacred Heart.” In receiving the Eucharist we firmly believe his very heart comes to beat inside of us as well. As we are about to gaze upon the cross, let us say from the bottom of our hearts, like the tax collector in the temple, “God, be merciful to me a sinner!” and then we too, like he did, will return home “justified” (Lk 18:13-14).

Translated by Marsha Daigle Williamson