The extraordinary beauty found from one end of the Eternal city to the other is in large part due to St. Peter.

Lenten Campaign 2025

This content is free of charge, as are all our articles.

Support us with a donation that is tax-deductible and enable us to continue to reach millions of readers.

On the 500th anniversary of the Protestant Reformation, this series of articles looks at how the Church responded to this turbulent age by finding an artistic voice to proclaim Truth through Beauty. Each column visits Roman monuments and looks at how the works of art were designed to confront one of the challenges raised by the Reformation with the soothing and persuasive voice of art.

The extraordinary beauty that accompanies visitors to Rome from one end of the Eternal city to the other is in large part due to a Galilean fisherman named Simon, now better known to us as St. Peter. The death of the “Prince of the Apostles” at the hands of Emperor Nero around the year 67 determined that Rome would be the seat of the Christian Church. The conclave elects the Bishop of Rome, and as successor to St. Peter, the pope is entrusted with the solemn duty of conserving and transmitting the deposit of the faith.

The legacy of Peter saw plenty of upsets over the centuries—temporal threats from the secular princes, invasions by Saracens and even the 70-year exodus of the papal court to Avignon in France—but the Protestant Reformation brought an entirely different challenge to the Petrine succession. It claimed that the papacy had no importance at all in the life of the faithful.

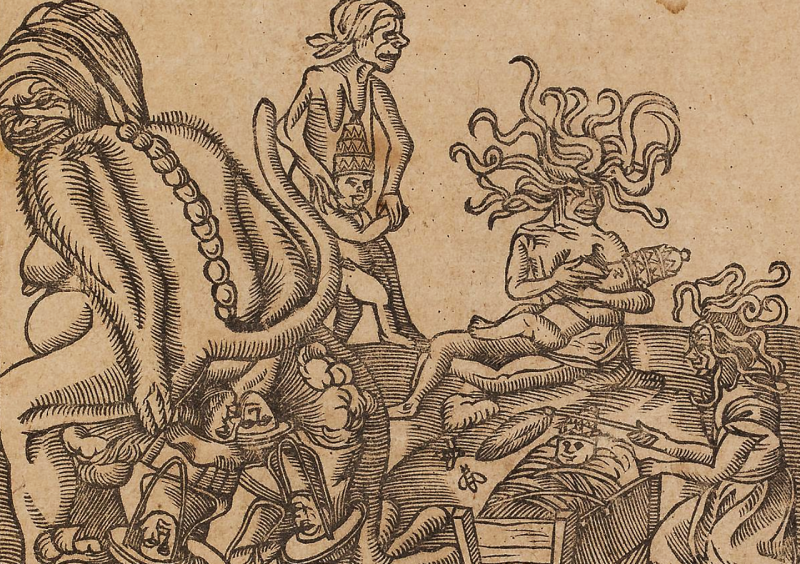

Martin Luther began by questioning the authority of the pope derived from Christ’s statement to Peter that “you are Peter, and on this rock I will build my church, and the gates of hell will not overcome it” (Mt. 16:18), claiming that the papacy is instead a human institution created by men. By 1545 Luther was writing Against the Papacy at Rome, Founded by the Devil, in which he railed against Rome, saying it is “very easy to prove that the pope is neither the commander or head of Christendom, nor lord of the world above emperor, councils, and everything, as he lies, blasphemes, curses, and raves in his decretals, to which the hellish Satan drives him.” (This is some of his milder invective—approved for all audiences).

The illustrations by Luther’s friend Lucas Cranach have become gone down in history as the first Charlie Hebdo-type satire. The Protestants had struck at the root of the Catholic tree theologically, scripturally, historically, and artistically.

The problem was aggravated by the Reformers’ co-opting of St. Paul as the principal apostolic authority. Roman tradition had always seen Peter and Paul as twins: dying on the same day, June 29, they were born simultaneously in heaven, and like the twins Romulus and Remus, they became the twin founders of Christian Rome. A millennium of images showing their respective martyrdoms, as well as the joint feast of Peter and Paul, commemorated the brotherly bond between the two: the Protestants had broken that bond.

On the artistic front, Church fought fire with fire, unleashing the towering inferno of Michelangelo. Fresh from his answer to the Protestants in the Last Judgment, the 68-year-old artist was given two prestigious commissions. The first was to complete the magnificent basilica dedicated to St. Peter, marking the tomb of the prince of the apostles, and the second was to paint the Pauline chapel. Cranach and his “Pope as Antichrist” wood cuts never stood a chance.

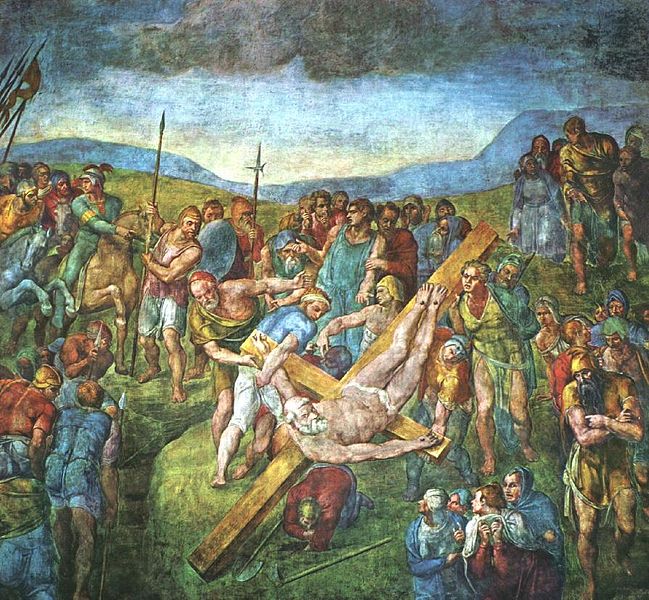

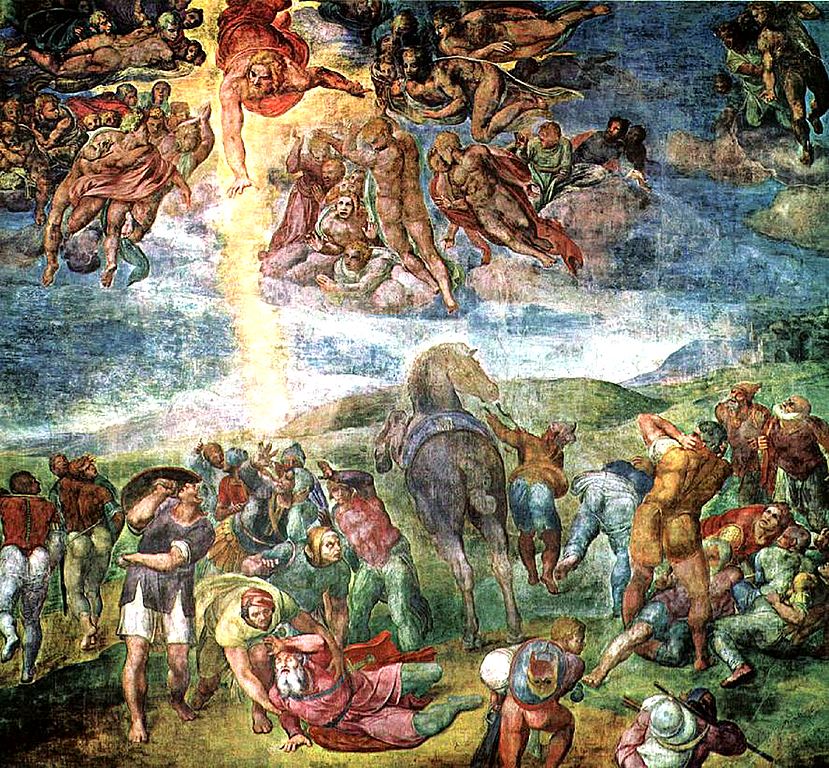

The Pauline chapel was built for the pope’s personal Masses, adoration of the Blessed Sacrament and the conclave. The most Roman Catholic of spaces, it underscored mystery, magisterium and martyrdom. Michelangelo frescoed the side walls with an usual pairing of pictures — the right wall showed the Crucifixion of St. Peter, but the left wall illustrated the Conversion of Saul. This new combination, requested by the pope, reiterated the significance of Peter’s ultimate witness, which took place a stone’s throw from the chapel, but was now complemented with Saul’s encounter with Truth. This image served as a reprimand to the Protestants, a summons to turn from the wrong road and return to the light and the way.

Recent cleaning has revealed that Michelangelo, despite age and eye trouble, had lost none of his artistic power. The colors are mesmerizing, the composition fascinating, and message powerful. In the Crucifixion of St. Peter, people swirl in turbulent eddies around the dominant figure of the apostle. Michelangelo, for the first time since his youth, displayed a dazzling palette of lapis, mulberry, mustard, cranberry and olive in the crowd, highlighting Peter, powerfully illuminated, as he represents the naked Truth bared to the world.

Helpless women weep, curious onlookers approach, soldiers bustle, men discuss, but Peter lies stretched on his cross, impervious to the drama around him. He lifts his head to stare directly at the viewer, which in the case of the conclaves held in the chapel was potentially a future pope, reminding his successors that this is the real job description: unflagging witness no matter the immediate situations and dramas. Peter’s fierce gaze then follows the newly elected pope from the altar and out the door, a daunting example.

Across from Peter, Saul lies stunned on the ground. Blinded, Saul holds his hand over his eyes as he struggles to rise. The intensity of this encounter is like a missile hitting the ground; most figures run away in fear, the remainder cower before the heavenly manifestation.

Christ, spectacularly foreshortened as to appear to fly down towards Saul, emits a ray of dazzling light that cuts through clouds and crowds to find its mark. Christ’s other hand gestures forcefully towards the distance, indicating to Saul to get up and go. As the viewer walks by, he is first confronted with the shock of Saul’s realization of his errors and then follows Christ’s hand to see a city further away — conversion is good, but conversion and witness is better.

Fifty years after the completion of the Pauline chapel, Pope Clement VIII thought to repeat this Petrine emphasis for the Jubilee year 1600, and turned to his treasurer, Tiberio Cerasi, who commissioned a chapel in the church of Santa Maria del Popolo. This church, the first one pilgrims would see upon their entry into Rome through the northern gate, had a special significance in the Counter Reformation. The church run by Augustinians, the same order as Martin Luther, was the first place that the young monk Luther had preached 90 years earlier. To exorcise this memory, Cerasi chose Caravaggio, catapulted to fame a year earlier with his St Matthew series in San Luigi dei Francesi.

For his second public work, Caravaggio (whose real name was Michelangelo Merisi) was competing with the legacy of his Florentine namesake who had died 7 years before he was born. The subjects would be the same, the Martyrdom of Peter and the Conversion of Saul, but where Michelangelo had covered great expanses with fresco, Caravaggio had one third the space and was working in the less prestigious medium of oil. Furthermore, his archrival, Annibale Carracci, had already been awarded the altar piece so his bright colors and virtuoso foreshortening would compete for the viewer’s attention.

Caravaggio dared to redesign the images entirely. Where Michelangelo painted crowds, Caravaggio painted intimate seclusion; where Michelangelo had cobalt skies, Caravaggio painted encroaching darkness.

His Crucifixion of St. Peter features four figures versus Michelangelo’s 50. All four are hard at work; three are laboring to complete the execution, while Peter’s task is to stay the distance. The three executioners have been reduced to muscle groups, a red deltoid, a yellow gluteus, a green trapezius all flexing like powerful cogs in a machine. Their faces remain in darkness, they are unknown and unknowing; they could be anyone, in ignorance, blindly working to destroy the faith. Peter, however, is bathed in a light so powerful it beautifies his bulky body and reveals his full knowledge of his mission. He gazes at the nail in his hand as if to grasp it even tighter, for through this trial he will receive the greatest reward.

A large stone lies in the foreground, a play on Peter’s name, which means rock. After a long journey, the pilgrims can take heart; only a few more steps to the place where the rock was laid to rest. The reality of St. Peter, his death in Rome, his body under the high altar of the newly completed basilica, would be made present to them though the stark painting of Caravaggio, along with the reminder that St. Peter didn’t die for the teaching of Luther, but those of Christ whom he knew and followed to his brutal death in Nero’s arena.

The Conversion of Saul emphasized the intimacy of conversion. Caravaggio further reduced the number of figures to three. The canvas is almost entirely occupied by a heavy workhorse and its handler, pausing as Saul lies on the ground. The inverted gymnast Jesus of Michelangelo is gone, and all that is left is His light, which, unnoticed by the animal or its master, beams down on Saul alone. Saul’s spiritual awakening is personal, and he receives it open-armed. Caravaggio uses minimalist tones of brown and beige in most of the space, until he reaches Saul. There the palette ignites as the red cloak spread below him and the orange cuirass evoke the colors of fire. Caravaggio’s hues illustrate the kindling of the Holy Spirit as Saul begins his transformation into the Apostle of the Gentiles.

Caravaggio did absorb one important lesson from Michelangelo as he worked on his canvasses. Michelangelo’s Pauline compositions focused downwards in both frescoes, leading through the jumble of characters to the heroes placed at the lower edge of the work. Traditionally, art tended to lift the eye upwards in compositions, but Michelangelo’s inverted V-shape challenged that.

Caravaggio would take it much further in his art, stressing prostrate protagonists at the bottom of his canvases. This humble position, prone and vulnerable, became a favorite of the artist, reminding the faithful, who would often have to bow to examine his works more closely, that humility is the key to sanctity. Peter and Paul accepted the humiliations of sin, error, derision, and persecution, but emerged purified and powerful ready to navigate the fledgling church into its great journey through centuries, continued by the unbroken line of Peter’s successors.