A look at the preliminary sketches that summarize the argument of the saint’s book in a clear, straightforward manner.

Lenten Campaign 2025

This content is free of charge, as are all our articles.

Support us with a donation that is tax-deductible and enable us to continue to reach millions of readers.

The Ascent to Mount Carmel (Subida al Monte Carmelo, in the original Spanish) is probably the best-known spiritual treatise of the Spanish Baroque. Written between 1578 and 1579 by St. John of the Cross — “the most mystical of all poets, and the most poetic of all mystics” — after his escape from prison, this book is a detailed, systematic, thorough explanation of ascetic life, mystical union with Christ and negative theology. In fact, when read alongside The Dark Night of the Soul – another of John of the Cross’ treatises — and The Living Flame of Love and the “Spiritual Canticle” (all of them considered to be some of the greatest works of all times in both Spanish Literature and Christian mysticism), one discovers a common trace: a narrow path that goes from both earthly and spiritual privations to the summit of Mount Carmel itself, where “only the honor and glory of God dwells.” This is, of course, a metaphorical image of the soul’s ascent towards the unio mystica, after leaving appetites and ties (cuidados, “cares,” the saint would write) behind.

The book, it must be said, is not an easy nor a quick read. Divided into three sections, and thought of as a commentary on the saint’s own allegorical poem The Dark Night, the treatise describes a of inner purgation that might be hard to follow at times. Having studied at the University of Salamanca, John of the Cross uses both scholastic philosophy jargon and the theological fundamental language of the 16th century to refer to both psychic and spiritual realities we might address in different terms today.

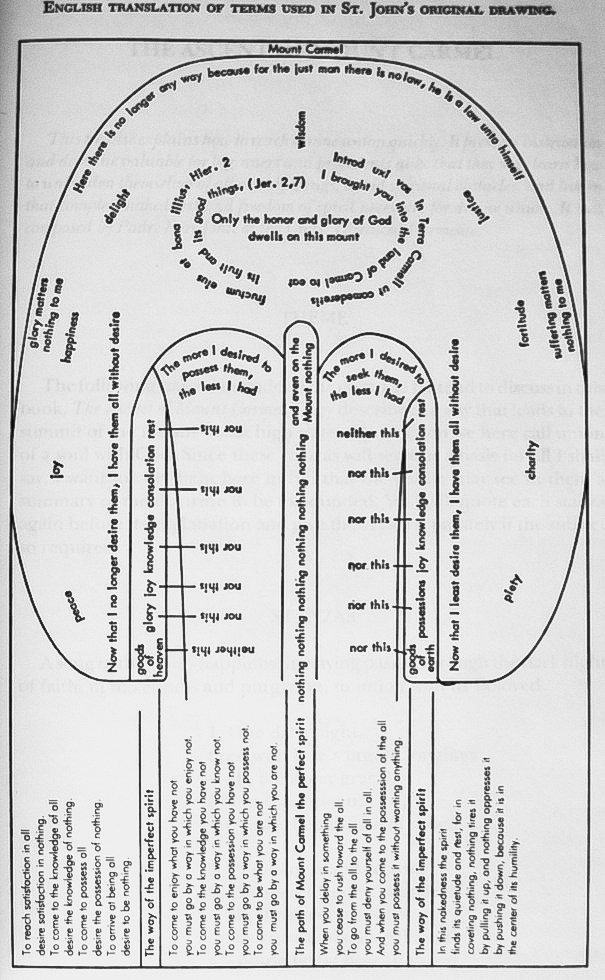

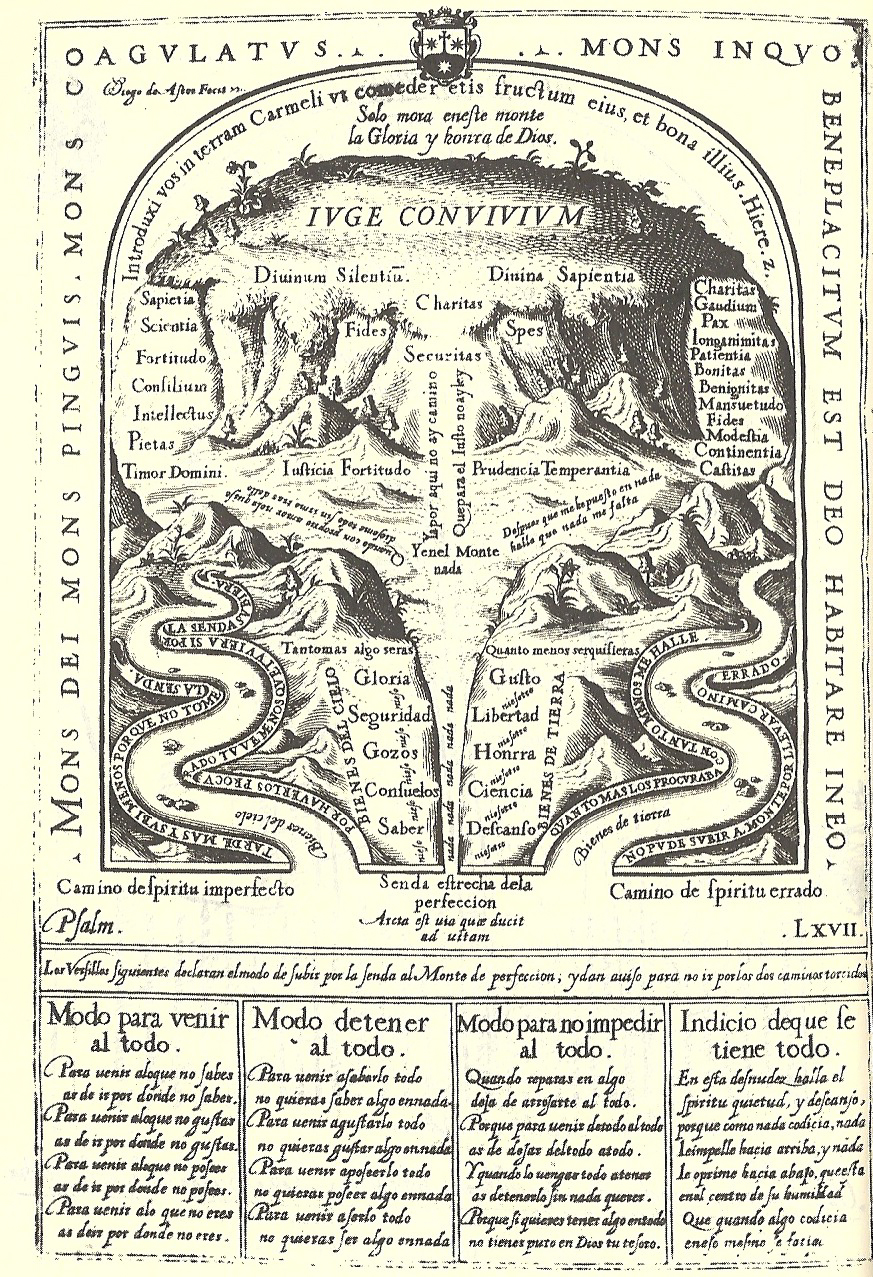

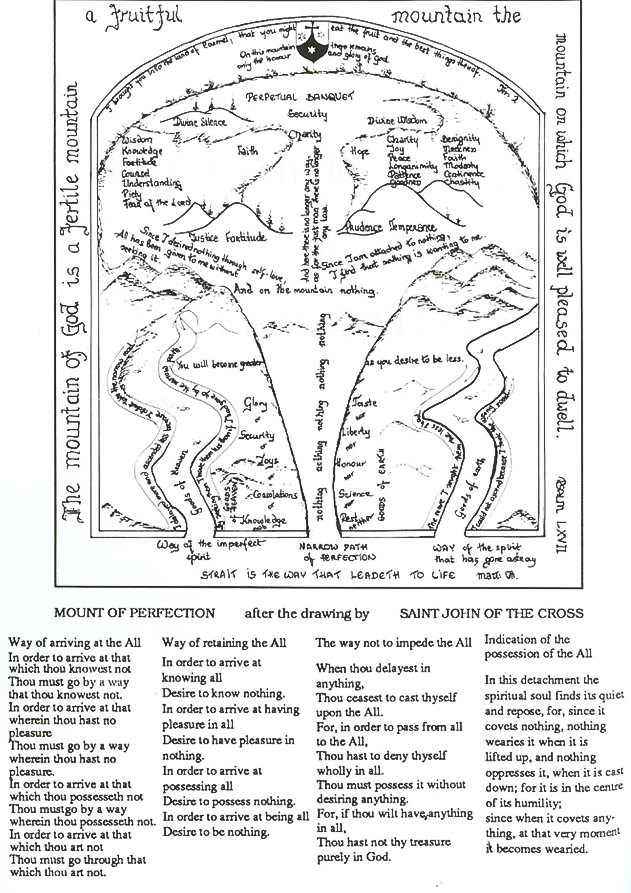

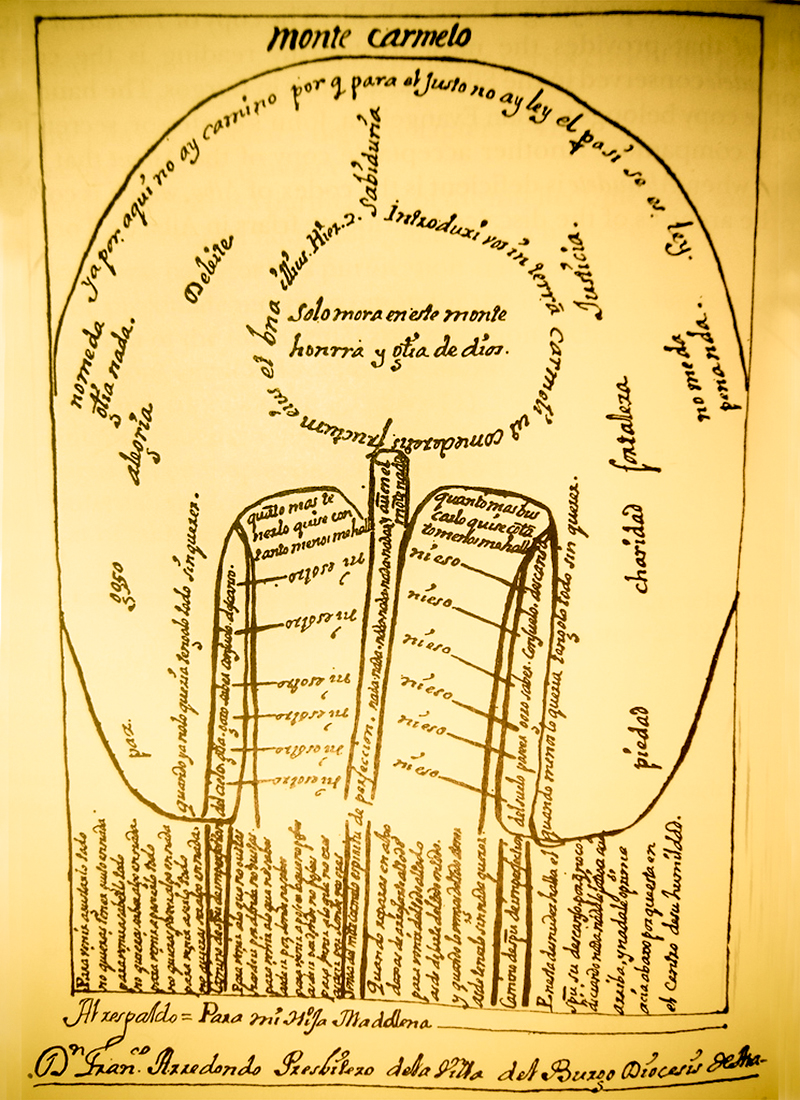

But John of the Cross also made some, let’s say, preliminary sketches that summarize the argument of his book in a clear, straightforward manner. In fact, he not only drew the Mount and the narrow path that leads to its summit, but also included two paths that lead elsewhere, and reduced his 3-section treatise to a few aphorisms and rhymes one can read in the drawings below. We have included the original drawing by John of the Cross (in Spanish); a later, more elaborate drawing (also in Spanish); and two English translations made after the original.