For one week, a Topeka, Kansas paper operated as if Christ were the editor.

Lenten Campaign 2025

This content is free of charge, as are all our articles.

Support us with a donation that is tax-deductible and enable us to continue to reach millions of readers.

“What Would Jesus Do?” was everywhere in the 1990s. Bracelets, placemats, tee shirts, coffee mugs, sterling silver rings, lunch boxes, bumper stickers and on. WWJD products are still available, as a cursory search of eBay and Amazon reveals.

Everything has a history; so does WWJD. It appeared in 1891 sermon preached by an English Baptist evangelical pastor, Charles Spurgeon (d. 1892), the Billy Graham of his day. He laced his sermon with the refrain “What Would Jesus Do?” Spurgeon used the phrase in quotes, and he specifically attributed it to Thomas à Kempis (d. 1471) and his devotional classic The Imitation of Christ.

Asking “what would Jesus do?” isn’t a bad contemporary English rendering of the original Latin, De Imitatione Christi. The Imitation is said to be the most widely read Christian devotional work next to the Bible. It counts both Catholic and Protestant Christians as readers and, clearly, at least one 19th century English evangelical Baptist.

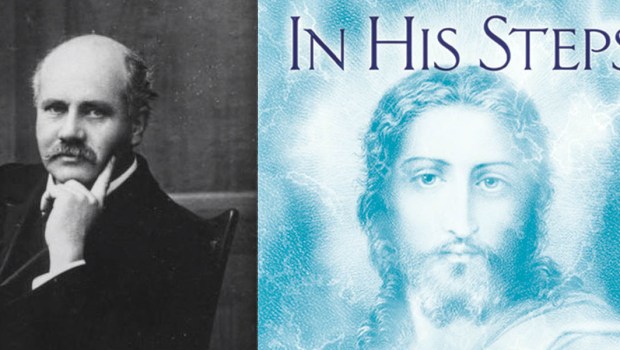

That brings us to Charles Sheldon (d. 1946), a Congregationalist pastor at Central Church, Topeka, Kansas.

Sheldon used the phrase in his 1897 novel, In His Steps: What Would Jesus Do? It depicts a community transformed when people stopped to ponder WWJD. It sold 30 million copies and is still in print. Some 70 American, Canadian, and British publishers re-published it without permission, thanks to a cloudy copyright. (I don’t think Jesus would do that.) In His Steps includes an episode imagining news editors asking WWJD. Jesus ran the newspaper.

Sheldon was a leader in the social-progressive wing of Christian Protestantism, one of the precursors of what came to be called the Social Gospel. It was more than closing saloons, though he was all for that. He founded an early-education school for African-Americans, the first one west of the Mississippi, and organized a community improvement society that, among other things, aided the unemployed. He was an essayist for The Christian Herald, an early sort of Christian Century.

Enter the publisher – getting back to Jesus — of the Topeka Capital (known these days as the Capital-Journal). Frederick O. Popenoe made an offer to Sheldon to test out a Jesus editorship. Sheldon may have had a major city paper in mind, but for Popenoe’s purposes, Topeka would do.

Popenoe, my guess, saw a chance to put his newspaper in the news and perhaps revive its sagging finances. (The paper was sold in a bankruptcy settlement the next year.)

But for a week in March 1900, Sheldon channeled Jesus in a Topeka newsroom.

First off he banned the newsroom denizens from cussing. He also prohibited smoking in the newsroom, tobacco spitting in the newsroom, and booze in the newsroom. It’s hard to say which pinched more but under Sheldon, the newsroom would be as moral as Sunday church.

Sheldon replaced the Sunday paper (related to Sabbath work) with a Saturday evening edition that, for a front page story, featured the Sermon on the Mount. He created high bars for advertisers: no ads for ladies underwear illustrating actual ladies; no corset ads (ahead of his time, Sheldon deemed them injurious to women’s health); no “bargain sales” (unless the previous price could be verified); and no patent medicines because their health claims were not substantiated.

He emphasized “positive” news, de-emphasized political scandal and crime, dropped coverage of professional boxing, and by highlighting a raging India famine, raised a million dollars or better for food relief (Sheldon was paid $5,000 for his editorship, all of it donated to the famine effort).

In that one week daily subscriptions rose 11,000 to 350,000 by week’s end. Demand was so intense editions had to be printed in Chicago and New York. Popenoe took commercial advantage of the experiment by jacking local advertising rates which, incidentally, priced most Topeka advertisers out of the market.

Whatever Sheldon’s original intent it was all ended up as novelty and novelty sold the papers.

It was an advocacy newspaper, filtering news through the lens of faith to impact personal behavior. Sheldon defined “news” as what “the public ought to know for its development and power for life of righteousness … what seems to the editor [Sheldon] to be the most vital issues that affect humanity as a whole.” Sheldon would ask WWJD and print the answer.

This was a time when progressive Protestants believed Christianity could re-shape the world by law, example, social pressure, and civic improvement, creating a better, more Christian people (even while being virulently anti-Catholic and anti-Semitic). There were theological assumptions too, notably, that public policy could extend heaven to earth. Once you’ve answered WWJD (say, about school funding), is there anything to debate afterward?

It was a confident self-assured movement, a “muscular” Christianity as the phrase has it. But it died in the wake of Depression and two world wars, and as with a good part of the Western world today, lost confidence in itself. That world was parodied by Sinclair Lewis in his take-down of a fictional evangelical, Elmer Gantry.

Today, the Capital-Journal is an ordinary yet well-respected daily delivering news and opinion to a diverse weekday readership of around 35,000; the Sunday edition reaches 44,000 readers.