How Christ’s journey to Heaven has been depicted in art over the centuries.

Lenten Campaign 2025

This content is free of charge, as are all our articles.

Support us with a donation that is tax-deductible and enable us to continue to reach millions of readers.

It is the fortieth day after Resurrection. We are back to the square where Jesus entered into His Passion – The Mount of Olives. At this moment Jesus having culminated His earthly life is now passing from the world to His Father. He has assigned to His disciples the task of announcing the Gospel and has promised to send His Helper. Amid astonishment and gasps He is then lifted from their sight.

As the apostles stare into space, their astounded gaze is interrupted by the address of the heavenly beings. “Men of Galilee, why gaze in wonder at heavens? This Jesus whom you saw ascending into heaven will return as you saw Him go.” (Acts 1: 6 – 14).

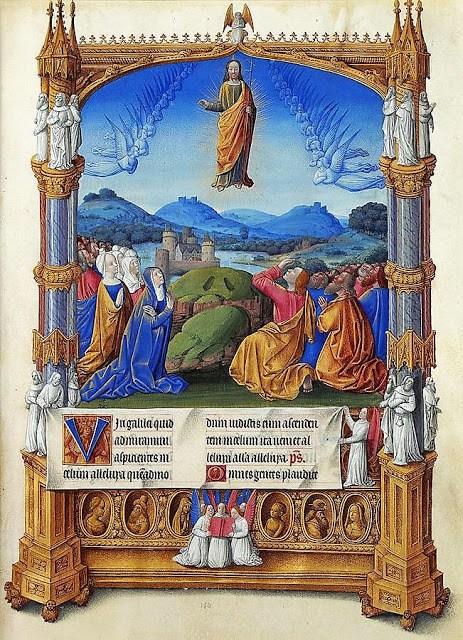

The theme of the Ascension naturally inspired art. Paintings dating back to the 5th century often depicted the episode in two zones: the earthy and the divine. While in the spiritual sphere Christ is portrayed ascending into heaven, the main characters of the terrestrial sphere include the disciples, the Blessed Virgin Mary and of course the angels.

The depiction of the Ascension was subject to interpretation and iconography. Through today’s article we will journey through history and its varied frames of the Ascension bound by fantastic forms, features and illustrations.

The earliest depiction of the Ascension is that of Christ marching forth on a mountain, grasping hold of a hand that pierces the earthly frame through the clouds. The hand, undoubtedly, is that of God the Father whom “no man could behold and live” (Exodus 33:20). Here, Christ having completed His earthly mission was welcomed by His Heavenly Father into His glorious kingdom. This depiction can be dated to the 4th century.

In the 14th century, Giotto follows a similar pattern minus the hand of the Almighty. In his prominent painting Christ is shown piercing the gates of heaven with His own hands while the angelic host surround Him in shouts of joy. The earthly characters continue to gaze upwards in prayer and amazement.

After the representation of the hands came that of the feet. The Ascension of Christ was emphasized by depicting Him leaving the pictorial space. Only His feet and lower legs were now visible. The rest of His appearance was engulfed in billows of clouds. The Virgin and the apostles stood witness to this event. This image was prominent during the Middle Ages.

Enhancing upon this style, the scene was given a twist in the 15th century. While Christ ascended into heaven, He left behind two tiny foot-prints upon the Mount from which He rose. Subtly, they served as reminders of Christ’s everlasting presence in the midst of His disciples. This presence would soon take the form of tongues of fire on the day of Pentecost.

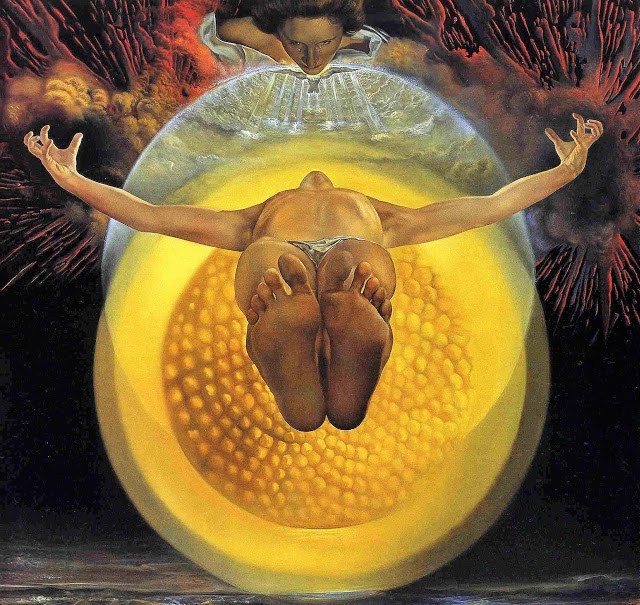

With the emergence of the 17th century the view changed. The viewer was now a part of the earthly sphere and of the painting itself. One could now see Christ from below disappearing into the clouds. His feet were wounded and foreshortened. The best illustrations of this scene were undoubtedly executed by the Flemish artist Peter Paul Rubens (1620) and the modern Spanish artist Salvador Dali (1958).

The final and the most famous depiction of the Ascension is that of Christ striding into heaven in a frontal posture. His appearance is augmented by a mandorla of light or that of cherubs (Renaissance). The mandorla was often in the classic almond shape. This motif was inspired by Roman mythology that dictated the transportation of the deceased into heaven on the wings of an eagle or other flying spirits. The mandorla was soon succeeded by clouds. This not only enhanced the drama but also the significance. To fathom its connotation one may recall the “pillar of cloud” that assisted the Israelites on their journey to the Promised Land. The cloud was the sign of the unseen God and His divine omnipotence.

While the representation of Christ in the theme of the Ascension changed over the ages one may wonder what happened to the earthly characters. They continued to fix their gaze on Jesus as He disappeared from their visual field and entered their spiritual hearts. Their eyes of faith convinced them that the stage was set for the Descent of the Spirit. The Fire of Pentecost would soon transform their lives like never before; mediocrity would give way to martyrdom. They would live and die for their faith which they proclaimed to Judea, Samaria and to the ends of the earth.

If you want to enjoy some other representations of the Ascension, please click “Launch the slideshow” in the image below:

This article is published in partnership with Indian Catholic Matters.