A useful guide to unlocking the symbolism in sacred art.

Lenten Campaign 2025

This content is free of charge, as are all our articles.

Support us with a donation that is tax-deductible and enable us to continue to reach millions of readers.

What symbols accompany the Risen Christ? Why does Judas wear a yellow garment? Which apostle is portrayed next to Jesus? Religious art is meant to communicate the Good News. Here are a few keys to unlock the symbolism in sacred art.

Depictions of God

Traditionally, Judaism prohibited the representation of God: “You shall not make idols out of stone” (Exodus 34:17). Christianity breaks with this tradition by representing God made flesh in Jesus Christ, adored by the Magi or snuggled in his mother’s arms.

Some depictions highlight Christ’s humanity, others his divinity. In early times, Christ’s divinity needed to be reaffirmed before unbelievers: the Christ Child is represented in a staid posture wearing a Byzantine-style ceremonial robe. In the Renaissance, when the divinity of Christ is widely recognized, the child is represented nude, emphasizing his true human nature. Many representations show his wounds and his suffering.

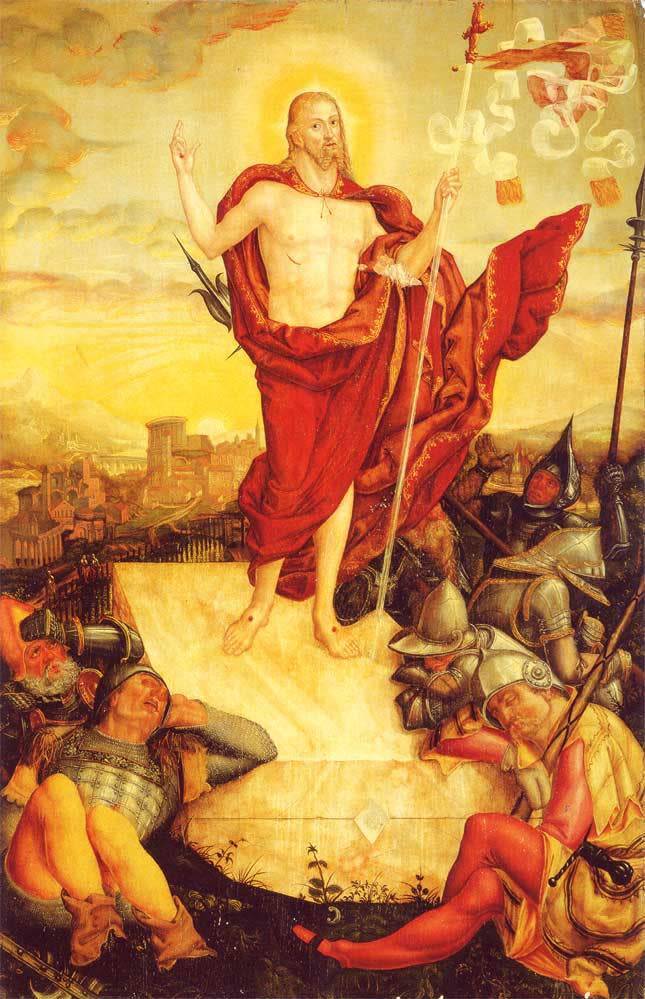

The Risen Christ

At Easter, Christ appears to Mary Magdalen with a resurrected body. In artistic depictions, the Risen Christ is often shown wearing a white garment, or a simple shroud. In some paintings the garment is red, in which case the marks of his suffering are usually also depicted. He may also be holding the standard of the resurrection: a white flag marked with a red cross.

In paintings of the 17th and 18th centuries, the attributes of the resurrection tend to disappear. Christ is more often represented as a gardener. In these depictions, he may be accompanied by Mary Magdalen.

Images of Mary

In the Byzantine era, Mary is often depicted on a throne. The footstool upon which she rests her feet is an imperial symbol. Her countenance is fixed and unperturbed, a sign of holiness. She is often larger than the other figures portrayed, with a star above her head.

During the Renaissance, Mary is painted as a simple woman, looking more natural and ordinary. She wears traditional robes of blue and red or blue and white. From the 19th century onwards, following the proclamation of the dogma of the Immaculate Conception, she is frequently crowned.

The Apostles with the instrument of their martyrdom

The Apostles are often depicted with the instruments of their martyrdom: an ax for Matthew and Mathias, a cross for Philip, an X-shaped cross for Andrew, a knife for Bartholomew, a lance for Thomas, a club for James the Less, a saw for Simon, and a sword for Paul.

The apostles can also be identified by other features and symbols. Peter is generally painted with a white beard, bald or with short white hair. He often carries a key or wears a papal tiara. He is sometimes accompanied by a rooster, symbol of his denial. Andrew the fisherman carries a net. John is usually depicted as a young beardless man with an air of innocence. His symbol as evangelist is an eagle. He has also been depicted holding a chalice containing a snake. St. James the Greater is represented as a pilgrim on the way to Compostela.

Symbolic colors

White evokes purity and eternity. It is most often the color of the Risen Christ’s clothing. Red symbolizes blood, war, and fire. Green evokes hope and blossoming love. Blue, once a neutral color, was confused with black — color of mourning and despair — before becoming the beacon color of the West, associated with Mary. Yellow is the color of traitors or renegades, of decline, illness, and demons — hence the frequent depictions of Judas wearing yellow.

With these tips, we’ve only scratched the surface of the symbolism found in religious art, but we hope they will help you understand better the works that surround us in churches and museums, on holy cards, in illustrated Bibles, etc. If this has piqued your curiosity, don’t hesitate to peruse the many other articles we’ve published at Aleteia regarding Christian symbolism!