A nation described in the Hebrew Bible as enemies of the Israelites, the Amalekites are also the descendants of Esau.

Lenten Campaign 2025

This content is free of charge, as are all our articles.

Support us with a donation that is tax-deductible and enable us to continue to reach millions of readers.

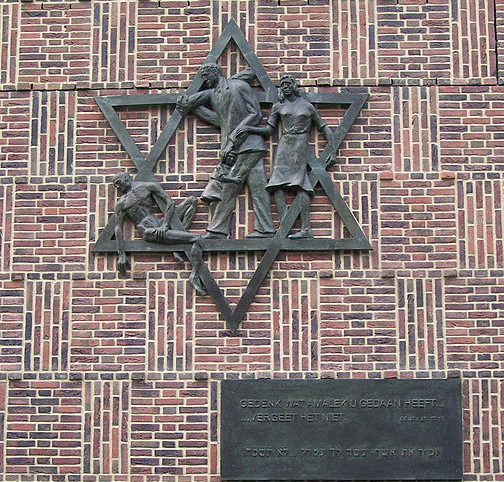

In a sculpture at the Holocaust Memorial in The Hague, a Star of David sculpted by the Dutch artist Dirk Stins in 1967, one reads a quote from Deuteronomy (Dt 25:17-19): “Remember what Amalek has done to you … do not forget.” Who is this Amalek Deuteronomy is telling the Israelites not to forget about?

The Amalekites are often referred to in the Hebrew Bible as “the sons of Amalek,” or also just as “Amalek,” referring to the nation’s founder, Amalek, the grandson of Esau. How could the grandson of Esau become the ancestor of the quintessential enemy of the Israelites? To better understand who Amalek is and what he stands for, we need to go back two generations in the Bible and understand the dynamics at play in the relationship of Jacob and Esau.

Esau and Jacob are twins, although they could not be any more different. Their rivalry is suggested, from the very beginning, in the book of Genesis: chapter 25 clearly states that Esau was born before Jacob, who came out holding on to Esau’s heel, as if trying to pull him back into the womb so that he could be firstborn. In fact, the name “Jacob” comes from a Hebrew root that can be either translated as “to follow,” “to be behind,” “to supplant,” or as “heel.” But, in fact, their rivalry precedes even their birth. Genesis 25 reads:

Isaac prayed to the Lord on behalf of his wife, because she was childless. The Lord answered his prayer, and his wife Rebekah became pregnant. The babies jostled each other within her, and she said, “Why is this happening to me?” So she went to inquire of the Lord.

The Lord said to her,

“Two nations are in your womb, and two peoples from within you will be separated; one people will be stronger than the other, and the older will serve the younger.”

In the biblical narrative, Esau is presented as a rough, red-haired (the text only says he was “red all over,” though) hairy hunter who seems to be more interested in being out in the fields than in learning the skills he would need to develop to deal with the responsibilities that come with being the firstborn. Jacob, on the other hand, is described as either a simpleton, or as an “almost perfect man:” there are discrepancies here, on whether the Hebrew word tam should be translated in one way or the other.

We are all more or less familiar with the story: Esau goes to his twin brother Jacob as he comes back from the fields, hungry like the wolf. He begs Jacob to give him some “red pottage” (the word for “red” in Hebrew is “Edom”), probably a pun on his red hair. Jacob agrees and offers Esau a bowl of red lentil stew in exchange for his birthright (that is, the right to be recognized as firstborn son, thus having power and authority over the family). Esau, who cannot think of anything else but satiating his hunger, agrees. All “for a mess of pottage.”

According to the Talmud, the sale of Esau’s birthright took place immediately after Abraham died, the twin brothers being both 15 at the time. The Talmudic text also explains the lentils Jacob was cooking were meant for Isaac, their father. Lentils are traditionally associated with mourning (unlike most beans, lentils have no eye, a symbolic reference of the deceased no longer being seen). But they’re also a hearty meal, intended to give consolation to those who mourn.

Of course, there are plenty of apocryphal ancient writings on what really happened that day. Among them, the Sefer HaYashar (literally, “Book of the Just Man”) seems to be the most important, as the Bible itself mentions the book three times: once in the book of Joshua, once in Samuel, and once in Kings. Chapter 27 of the Sefer HaYashar explains that, after Abraham’s death, Esau would go frequently to the field to hunt, most likely as a distraction to deal with the loss of his grandfather. There, in the field, Nimrod, King of Babel, would see Esau from afar. The text explains Nimrod was envious of him. Eventually, Esau killed Nimrod and two of his guards, who were also hunting with him. Being persecuted by Nimrod’s men, Esau flees and tries to hide in Isaac’s house, where he finds his brother cooking. The Sefer HaYashar claims Esau willingly sold his birthright to Jacob:

And he said unto his brother Jacob, “Behold I shall die this day, and wherefore then do I want the birthright?” And Jacob acted wisely with Esau in this matter, and Esau sold his birthright to Jacob, for it was so brought about by the Lord.

In any case, willingly or not, by renouncing his birthright, Esau can no longer occupy the seat of the patriarch, which is now held by Jacob. That is why Jacob is considered the progenitor of the Israelites and Esau that of the Edomites (again, “Edom” meaning “red,” a reference to either Esau’s hair color, to the “red pottage” he trades his birthright for, or to both), the territory of Edom (referred to in Roman and Greek sources as “Idumea”) being located south of the Dead Sea, in territories nowadays corresponding to Jordan and Israel mostly.

Now, Amalek is referred to in Genesis 36 as being the son of Eliphaz, one of Esau’s sons. Eliphaz had a concubine by the name of Timna, who gave birth to Amalek. In the same chapter, Amalek is referred to as “one of the chiefs among Esau’s descendants,” meaning he either ruled a clan or some territory.

However, some other genealogies point out at a slightly different origin for Amalek and the Amalekites. In the book of Numbers, we find Balaam, a non-Israelite diviner, referring to Amalek as “the first of nations:”

“Then Balaam saw Amalek and spoke his message: ‘Amalek was first among the nations, but their end will be utter destruction.’”

Different sources (both classic and contemporary) claim the Amalekites existed even way before Abraham, and that they were the first nation ever formed after the Flood. But that aside, what the text seems to point at is that the Amalekites were the “first” in their hostility against the Israelites, as is suggested by Esau’s struggle against Jacob even in their mother’s womb. In fact, Amalek attacks Moses and his people (Ex 17:8) in Rephidim, as they are still wandering in the desert. Deuteronomy explicitly commands not to forget “what Amalek did to you:”

Remember what Amalek did to you on your journey out of Egypt, how he attacked you on the way, when you were faint and weary, and struck down all who lagged behind you; he did not fear God. Therefore when the Lord your God has given you rest from all your enemies on every hand, in the land that the Lord your God is giving you as an inheritance to possess, you shall blot out the remembrance of Amalek from under heaven; do not forget.

In that sense, the Amalekites are considered as the archetypal enemy of the Jews, an eternally hostile enemy beyond the possibilities of reconciliation of forgiveness, that is seen to come back once and again in history: Romans, Nazis, and Stalinists have been identified with Amalek throughout history — hence, Stins’ inclusion of this passage from Deuteronomy in his Holocaust Memorial.