Thomas Nast was also known for his unflattering depictions of Irish-Catholic immigrants and the pope.

Lenten Campaign 2025

This content is free of charge, as are all our articles.

Support us with a donation that is tax-deductible and enable us to continue to reach millions of readers.

St. Nicholas, far from the modern depiction of Santa Claus, was actually a 4th-century bishop, who lived in modern-day Turkey and earned a reputation for generosity after word spread that he secretly gave bags of coins to unmarried girls to protect them from being sold into prostitution.

But where did we get the idea that Santa Claus is from the North Pole?

The image of a white-bearded, pot-bellied, sleigh-riding, stocking-stuffing Santa actually comes from the political cartoonist Thomas Nast, also known for his anti-Catholic sentiments.

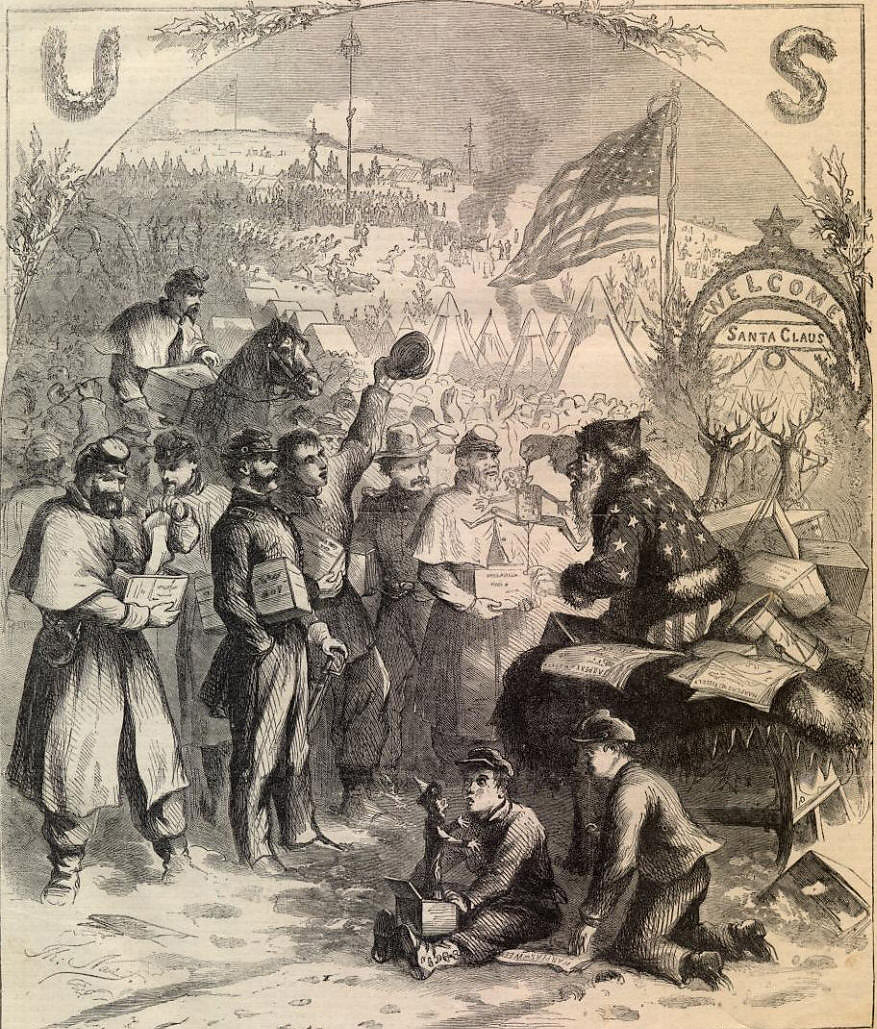

According to Smithsonian Magazine, our idea of Santa can be traced back to the January 3, 1863 issue of Harper’s Weekly, which included two of Nast’s cartoons, featuring a Jolly St. Nick amidst Union soldiers. Nast borrowed imagery from Clement Clarke Moore’s 1823 poem “A Visit from St. Nicholas” (known for its line, “Twas the night before Christmas”), and portrayed St. Nicholas with reindeer, sleigh and sack full of presents.

The cartoons were a bit of political propaganda — aimed at lending the Union cause a bit of Santa’s positive public image — but proved so popular that Harper’s Weekly published Nast’s Santa cartoons every year until 1886, cementing the idea of a North Pole Santa in America’s consciousness.

The anti-Catholicism of cartoonist Thomas Nast

As a supporter of the Union and an opponent of the Confederacy, Nast held strong political convictions. Chief among them was his contempt for the Democratic party, the corruption of the Tammany Hall political machine in New York and the Irish-Catholics he associated with it.

His cartoons reveal not only an anti-Irish immigrant sentiment, but Nast’s view that the Catholic Church, and the pope in particular, were a threat to the American republic.

In one cartoon, “‘The Promised Land’ as seen from the Dome of St. Peter’s Rome,” the pope and clergy are pictured from the top of St. Peter’s Basilica, with a telescope aimed at the United States, as if they were setting their sights on the nation in order to conquer it.

In one of his most famous cartoons, published in 1871, “The American River Ganges. The priests and the children,” bishops wearing pointed miters on their heads, are made to look like crocodiles ready to devour children, left vulnerable by the crumbling of American public schools. The message: Catholic schools are a threat.

View the slideshow to see some of Nast’s other anti-Catholic cartoons, which were published in Harper’s Weekly.

To read more about Nast’s anti-Catholic cartoons, visit the Catholic Historical Research Center of the Archdiocese of Philadelphia website.