Since its founding in 1882, the Knights have fielded their own teams, and at one point, more than 200 Knights played in Major League Baseball.

Lenten Campaign 2025

This content is free of charge, as are all our articles.

Support us with a donation that is tax-deductible and enable us to continue to reach millions of readers.

America’s first professional baseball team, the Cincinnati Red Stockings, formed in 1869. It would take another 13 years before Father Michael J. McGivney and parishioners at St. Mary’s Church in New Haven, Connecticut, founded the Knights of Columbus. At that point, Major League Baseball wasn’t established, but baseball was already the nation’s game.

It was a game Father McGivney loved. According to his biography, Parish Priest, the K of C founder helped form The Charter Oaks, a seminarian baseball team at Niagara University, for which he played left field. And as a parish priest, he organized ball games with his parishioners, enjoying the “snappy play” and action on the diamond.

At the time of the Order’s founding, Catholics were not held in high-esteem, often taking the most dangerous jobs for little pay. They were also seen as papists, loyal only to Rome, not as patriotic American citizens. But on the baseball field, it was about your skills, not your religion. Baseball was an avenue of integration and assimilation into American society.

For a fledgling fraternal organization, that was attractive. Baseball became the Knights of Columbus’ sport, which impacted not only inter-council relationships, but also the growth of the national pastime.

Baseball gains a foothold

The first mention of baseball in a Knights of Columbus publication was in 1894, the inaugural year of Columbiad, the Order’s magazine. It reported that on Saturday, August 18, the Natick and South Framingham, Massachusetts, councils held athletic competitions, including a baseball game in which the latter won 12 to 2. The following year, there was a game between Fitchburg and Worcester councils. The game was “enlivened by all the traditional features of interest” and even “threatened mobbing of the umpire,” but, in the end, “the best of feeling prevailed” as Fitchburg won the contest.

Knights in Massachusetts, Connecticut and New York increasingly began holding inter-council games. Not long after, games were played across state lines. In August 1897, a council in Concord had a baseball committee and arranged a rivalry game between Knights from New York and Boston. The nine-player teams competed for a “silver cup.” Although the score was not recorded, New York Knights won.

The Columbiad staff were so amazed by the significance of the event that they dedicated extra space in their issue to report the game. They added, “Baseball is gaining a great foothold among the Knights. … The national game is great sport, and there are, after all, but very few of us who do not enjoy it.”

From then, councils began forming their own teams —with light-hearted names such as the “Muskegon K. C. Champion Constellation Bloomer Boy Baseball Nine” and the “Grand Rapids Stupendous Convocation of Spherical Manipulators” — and even their own leagues.

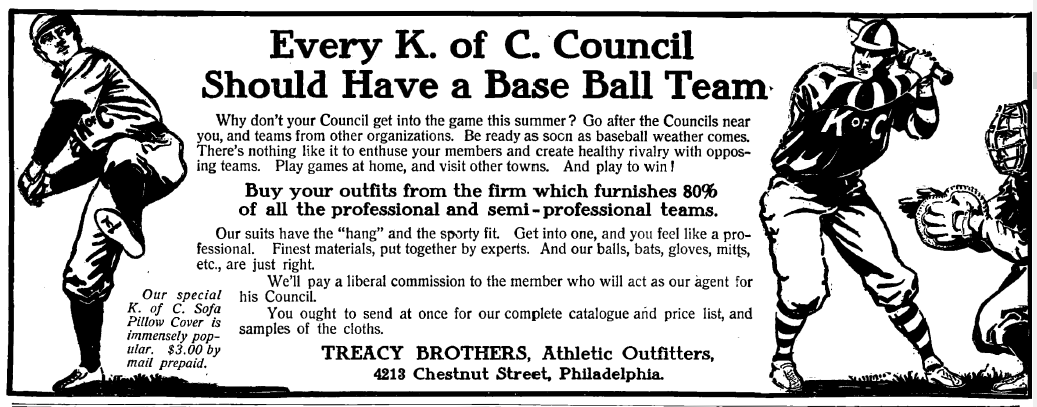

Every K of C Council should have a baseball team

At the beginning of the 20th century, several major cities including New York, Boston, Chicago and St. Louis had Knights of Columbus baseball leagues. Chicago was “recognized as the greatest and largest fraternal baseball league in the world” with 42 teams, enough for five divisions.

These were not simply pick-up leagues. They were widely attended and well-planned. As St. Luke Council 428 in New York City stated, “Only bona-fide members will be played.”

The players were members of the council with experience. Some played for their college teams. Some were semi-professionals. Others played in the majors, such as Joe Quinn — the first and only Australian-born native to play in the majors until 1986. Quinn played on one of the six St. Louis ball clubs in 1905. Future Hall of Famer Ross Youngs played shortstop for the San Antonio Knights of Columbus baseball team.

Many teams were highly regarded. The Knights of Columbus Baseball Team of Parkersburg, West Virginia, was considered “one of the best clubs in the Ohio valley,” while Pere Marquette Council 271 was said to have “the fastest baseball team” in Boston.

They were competitive, and councils prided themselves on putting a “strong team” forward. Teams would travel hundreds of miles to compete, like the Knights’ team from Braddock, Pennsylvania, who went undefeated playing all its games away from home not only across the state but also in Ohio and West Virginia. Teams were so competitive that, in one instance, St. Luke and Guiding Star Councils in New York played in the “very dark” with no lights until the game was over.

By 1911, Columbiad was running ads for baseball gear as well as stories about Knights in the majors. One prominently featured ad read, “Every K. of C. Council Should Have a Base Ball Team” and challenged readers to “go after the councils near you, and teams from other organizations.”

Knights responded, expanding the game throughout the country, and even into parts of Canada.

Wherever baseball is played, the K of C is prominent

It was reported in Columbiad that at one point, more than 200 Knights played in Major League Baseball. Some left an impressionable legacy on the nation’s pastime. Johnny Evers, second baseman for the Chicago Cubs, was part of one of the game’s fabled double-play combinations: Tinker to Evers to Chance. Connie Mack of the Philadelphia Athletics and John McGraw of the New York Giants set the standard for every other manager that followed, leading in all-time managerial wins. Future Hall of Famers such as Ed Walsh, Willie Keeler and Hugh Duffy set records that players chased for years, with some records still standing.

Knights were pillars of the game, expanding the game’s popularity locally and even internationally.

During the First World War, the Knights of Columbus volunteers — known as Caseys and secretaries — provided recreation for the troops. Their prominent recreation was baseball. The Knights sent thousands of bats, gloves, uniforms and even major league stars like the Evers and Hall of Fame pitcher Christy Matthewson to teach the game and entertain the U.S., British and French soldiers. The Knights even had entire teams comprised of African American soldiers, like one in Camp Zachary Taylor in Louisville, Kentucky.

Although the leagues’ standards subsided and eventually dissolved overtime, Knights continued to support the game and its mightiest heroes, such as Babe Ruth, Joe DiMaggio and Gabby Hartnett, who were also members of the Order. Councils around the country continued to sponsor Little League teams and leagues of their own. It seemed like, as noted by T.H. Murnane, a baseball writer for the Boston Globe, “Wherever baseball is played, the K. of C. is prominent.”

Of course, the Knights also sponsor and support other sports, but why was there a great affinity for baseball? Simply put, it was America’s game. The sport helped assimilate Catholic immigrants through the fraternal aspects of the game. It made Catholics part of the patriotic, American experience. Plus, as Father McGivney saw, it was also fun.

More from the Knights of Columbus history can be found in The Knights of Columbus: An Illustrated History. The book is available online and at local bookstores. It can be ordered at Amazon, Barnes and Noble and more.

Originally published in a weekly edition of Knightline, a resource for K of C leaders and members. To access Knightline’s monthly archives, click here. Republished here with kind permission.