Early Christians were hesitant to use a crucifix, which they saw as degrading, in the practice of their faith.For two centuries, followers of the new Christian faith avoided making a badge of honor out of the instrument of Christ’s death. Many non-Catholics still liken wearing a crucifix to hanging an electric chair around one’s neck.

The crucifix was seen as degrading

This was how the first Christian communities would have seen it too. Crucifixion was a form of execution designed to be both excruciating and humiliating. It was a deliberate public degradation. For pioneer Christian converts with a Judaic background, the figure of a crucified God was worse than degrading; it went against centuries of their religion and culture. No wonder they turned to words instead.

In the beginning there was “the Word”

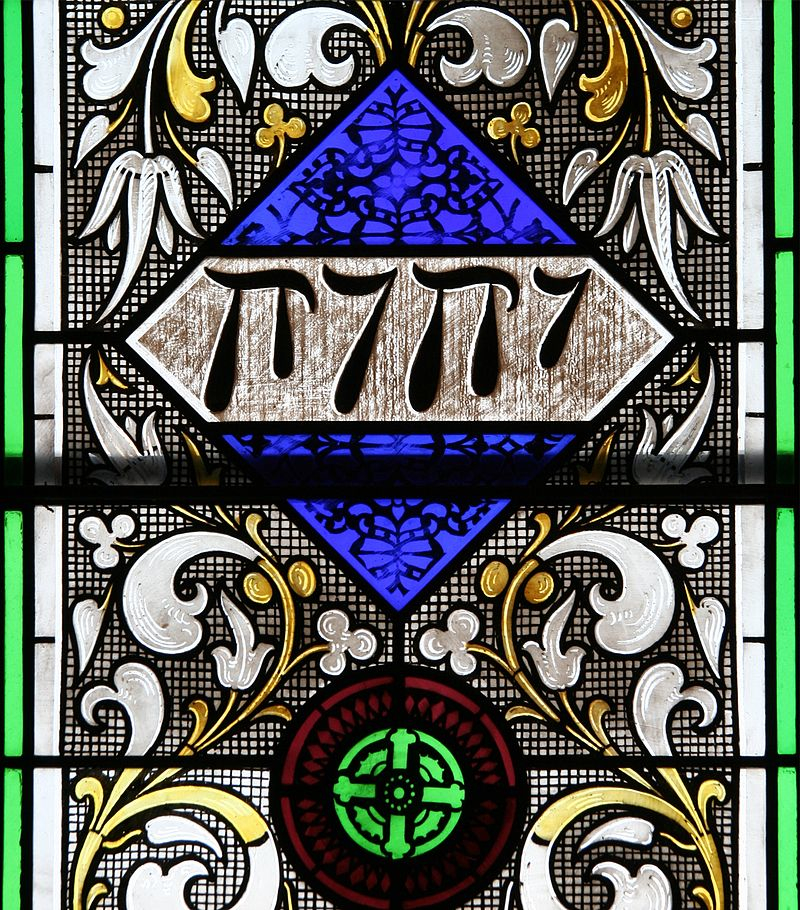

Christ loved words and telling stories with them. “I am the Alpha and the Omega” is used multiple times in the New Testament. As Greek was the lingua franca of the eastern Mediterranean, early Christians used the Greek alphabet to create a written symbol by which they could identify each other. Words were powerful in Hebrew, too. To this day, the Hebrew word for God (abbreviated to YHWH) is seldom spoken or written in full. It is referred to as “The Name.”

The early Christians were equally reticent about promoting the name of image of God. “Fish” was their first choice as a reference to Christ. Partly because their Savior spoke of being a “fisher of men,” and also because the Greek word for fish (ichthus) can have a double meaning: Jesus (Iesos) Christ (Christos) of God (theou) Son (uios) Saviour (soter).

Wordplay with Christ’s name is discussed more often than references to His cross. This shows how important the symbol was, before it was represented physically. Around the year 200, the theologian Hippolytus wrote about making the sign of the cross on the forehead “as this is a sign of His Passion.” Soon after, it was being recommended as a cure for scorpion stings. The idea of the cross had clearly taken hold.

The Staurogram

A contender for the earliest physical representation of Christ’s cross is the Staurogram. Composed of the Greek letters Tau and Rho, its sound was reminiscent of the Greek word to crucify, “stauroo.” Used mostly in written texts from the 2nd century, it actually resembles a person on a cross.

The Chi Rho Symbol

More widespread in its coverage was the Chi Rho symbol, which combined the first two letters of Christ’s name in Greek to form an image that looked less like a cross than the Staurogram. The Chi Ro is more reminiscent of the papal crossed-keys symbol. This is no coincidence, as popes continue to use both. These symbols convey some of the imperial splendor of Constantine the Great, who first adopted the Chi Rho. For good measure, the letters Alpha and Omega are sometimes added.

Graffiti or sacred imagery?

As Christianity traveled westwards it encountered cultures that not only enjoyed graven images, but often had no written language. The first example is, notoriously, a piece of graffiti by an anonymous semi-literate in Rome. It was certainly not by the hand of a Christian and there are many reasons to be doubtful about this image. It may count as a crucifixion but not the Crucifixion.

Putting a correct date on many of these supposed crucifixion scenes is another problem. It is thought that a carved gemstone in the British Museum could be the earliest non-blasphemous image of the crucifixion. It’s a troubling item, though. The amulet might have been produced by a heretical sect and clearly shows Christ attached to the cross with ropes instead of nails.

The ivory casket Crucifixion of Christ

My favorite contender as the first unequivocal representation of Our Lord’s death is an ivory casket, made in Rome around 420. It has all the attributes that we would recognize today. Mary and St. John mourn at the foot of the cross, while the Roman soldier Longinus is spearing the side of Christ. The victim is attached with nails. As a bonus, we can see the remorseful Judas hanging from a tree. Most convincing of all is that it brings us back to the written word. Above the head of the crucified man is half of the Latin title we know so well: “King of the Jews.”

View the slideshow above to see photos depicting early Christian symbolism.

The virtual Museum of the Cross

This crucifix is from the collection of the Museum of the Cross, the first institution dedicated to the diversity of the most powerful and far-reaching symbol in history. After ten years of preparation, the museum was almost ready to open; then came COVID-19. In the meantime, the virtual museum is starting an instagram account to engage with Aleteia readers and the stories of their own crucifixes: @crossXmuseum