Lenten Campaign 2025

This content is free of charge, as are all our articles.

Support us with a donation that is tax-deductible and enable us to continue to reach millions of readers.

Science is central to modern life. It is because of science that you are reading Aleteia on a screen, via the internet, not on paper, by the light of an oil lamp. This series of articles (click here for the whole series, which will be updated with future articles) dives deep into the story of the Catholic Church and science. The story goes back a long way. It is still unfolding today. It is not the story you might think you know. But it is a story you should know, exactly because science is so central to modern life.

~

The Church has been accepting persuasive science and figuring out how to interpret faith in light of that persuasive science for almost 2,000 years, since at least the question of the “two great lights” of Genesis 1 (see Part 1 in this series). But some of the Church’s best minds, St. Augustine and St. Thomas Aquinas, weighed in on that particular question. There is not always an Augustine or Aquinas around, and things have changed since Augustine, and even since Aquinas.

When there is a conflict between science and the Catholic faith, and there is no Augustine or Aquinas around, what does the Church do? Or, more specifically, what does the Vatican do? How are decisions made and actions taken when the subject is something like science?

There have been few instances where there was significant conflict between science and religion, of the sort where the Vatican got involved. The Church is not really going to have much opinion on most scientific developments. The debates of scientists about the existence of what we now call oxygen, or about bird migration, are unlikely to generate broad conflicts with religion.

One thorny issue

One instance where broad conflict did arise and the Vatican got formally involved is the theory of evolution. There is a lot of documentation about the processes the Vatican used during that conflict. That was only about 150 years ago — just yesterday in Church history! The Vatican kept plenty of records that have survived to today. In the late 20th century, the Vatican opened the archives containing those records so that scholars could study them. Therefore, there is plenty of information available about what went on when the Vatican was confronting the question of evolution.

Scholars have pored over that information and written about what they found. There were six faith-and-science cases involving evolution that reached the Vatican in the later decades of the 19th century. All were related to Catholics writing about the theory of evolution.

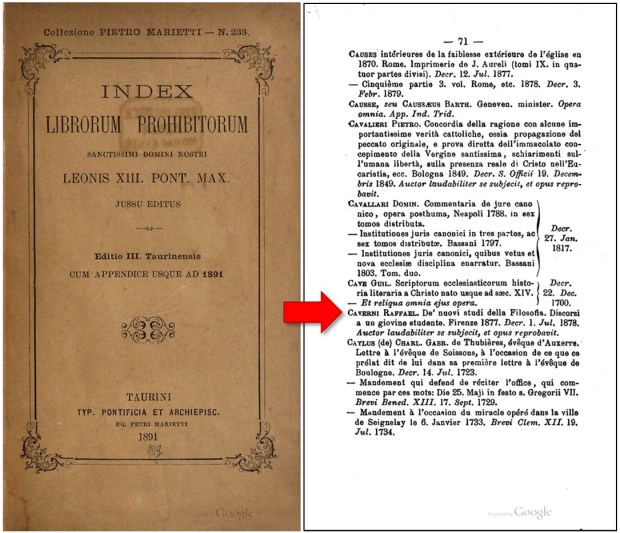

There were two Vatican groups that could address these sorts of cases. One was the Holy Office (later the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, now the Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith). The other was the Congregation of the Index (merged into the Holy Office by Pope Benedict XV in 1917). The Holy Office had a broad role regarding matters of faith and morals. The Congregation of the Index, which published the Index of Prohibited Books for more than three centuries, was much less important in function and rank. Its decisions were less important; its mission was much more concrete and modest. Nevertheless, when there was Vatican action in the six evolution cases, it was the Congregation of the Index that acted, not the Holy Office.

It turns out that the Congregation of the Index operated like many academic or parish committees — which is to say, imperfectly! The Congregation did not have any set program for reviewing books in general to catch ones the Church might find problematic. There was no plan of action. The Congregation only looked at a book when someone submitted a formal complaint to them about the book.

When that happened, the secretary of the Congregation was required to examine the book and to name book reviewers, called “consultors,” who also examined it. Someone in the group would write a report. There would be a meeting of the consultors. Then there would be a meeting of the full Congregation of the member cardinals. They would produce a judgement on the book, to be submitted for the pope’s approval. If a book was found to need censure, a decree was published, adding the book to the Index. But only that decree of condemnation was made public. The reasons why a book was condemned were not specified.

That is how things worked in principle. In reality, new editions of the Index were not issued with any regularity. The consultors and cardinals who were members of the Congregation did not attend meetings regularly, either. The Congregation consisted of 20 to 30 cardinals during the evolution discussions, but records show that usually only five or ten cardinals showed up at a meeting! Members of the Congregation had other priorities.

Then there were the reports. There might be multiple reports from different consultors, with the views of the consultors not agreeing with each other at all. In the case of Fr. Dalmace Leroy and his 1891 book The Evolution of Organic Species, Congregation consultors wrote six different reports over time! The consultors were not in agreement about Leroy’s book. They were not in agreement about evolution.

Consultors themselves recognized the weakness of the process. One of the consultors who reviewed Fr. Leroy’s book suggested that the cardinals not prohibit it, but rather just warn Fr. Leroy through his superiors to issue a retraction of the book on his own. Why not prohibit the book? In part because the consultor thought Fr. Leroy had good intentions and was a bright and upright priest. But in part it was because the consultor thought that Fr. Leroy should not be subject to having his book condemned when other writers had similar books in circulation that would not be condemned — not because those books were better somehow than Fr. Leroy’s, but simply because no one had complained about them to the Vatican.

Even the overall Congregation might hold back on their opinions. They did not always put a solid effort into their evaluation of evolution (as evidenced by the attendance at meetings), relying on their own efforts rather than consulting a wide group of experts. So sometimes they worried that their decisions were not above criticism from the top minds in theology.

Given the haphazard nature of the Congregation’s workings, it is not surprising that in five of those six evolution cases mentioned above, the Congregation took no official action, opting to either privately communicate with authors or to take no action at all.

The only book to be publicly condemned as a result of its treatment of evolution was the 1877 book, New Studies of Philosophy: Lectures to a Young Student by Fr. Raffaello Caverni, who had served as professor of physics and mathematics in the seminary of Firenzuola. But since the reason for a book’s being listed on the Index was never given, and there was no mention of evolution in the book’s title, no one who was not directly involved in the book review process would have ever known what the problem was. People knew Fr. Caverni’s book had been prohibited, but not why. Caverni had some criticisms of the ecclesiastical world in his book — for all anyone in the public knew, maybe that was why it was put on the Index. Unsurprisingly, the case of Fr. Caverni is usually overlooked in discussions of the Vatican and evolution.

The Vatican, like the Church as a whole, is made up of people — imperfect people. Imperfect people make for imperfect processes, imperfect actions, and imperfect results. That is important to keep in mind in exploring the story of the Catholic Church and science.

Of course, we might ask — if the Church’s processes are so imperfect, why would it ever get involved in a science question in the first place, if there was no heavy hitter like Augustine on hand? Isn’t science the best way we have of knowing things?

We'll look at that question in the upcoming articles.

~

This series is based on the paper “The Vatican and the Fallibility of Science,” presented by Christopher M. Graney at the “Unity & Disunity in Science” conference at the University of Notre Dame, April 4-6, 2024. The paper, which is available through ArXiv (click here), contains details and references for the interested reader.

The paper, and this Aleteia series, expands on ideas developed by Graney and Vatican Observatory Director Br. Guy Consolmagno, S.J. in their 2023 book, published by Paulist Press, When Science Goes Wrong: The Desire and Search for Truth (click here).