For Dr. Kim Paffenroth, what made George Romero’s zombie apocalypse so terrifying was how true to life it was.

Lenten Campaign 2025

This content is free of charge, as are all our articles.

Support us with a donation that is tax-deductible and enable us to continue to reach millions of readers.

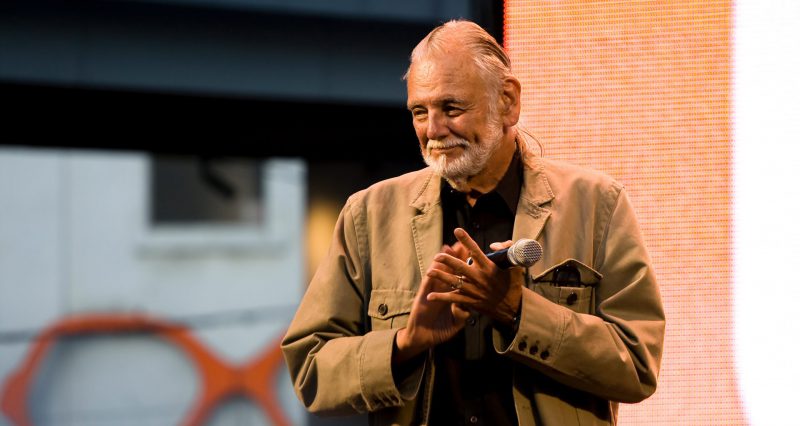

When George Romero passed away on July 16, the world lost one of its greatest horror filmmakers.

Romero’s 1968 film Night of the Living Dead, a stark black-and-white vision of flesh-eating ghouls surrounding a group of people in a Pennsylvania farmhouse, set the gold standard for zombie movies. Every movie or show about the walking dead since – including five sequels from Romero himself – bears the influence of that primordial nightmare.

But for Dr. Kim Paffenroth, a horror novelist and religious studies professor at Iona College, what made Romero’s zombie apocalypse so terrifying was not that the thought that it could happen. It was that, in many ways, it already is.

“For me, when I first saw Dawn of the Dead in theaters and Night of the Living Dead on a 5-in black and white TV, I knew, inchoately, that there was something different about the horror, that it was not just gore and death, but existential dread, living as unmoored, disconnected, alienated, meaningless…” That original experience stuck with him, resurfacing later in life when the Dawn of the Dead remake hit. “And at that point I had the vocabulary and critical analysis to say more about it, to articulate it beyond my 13-year-old self’s ‘Zombies. Cool.’”

Paffenroth thought through the usual political and social interpretations of Romero’s six-film franchise, but found something more elemental that connected them. “George disassembled, dissected our modern world – laid its dark parts bare that we’d rather have left hidden, just the way his zombies wandered around with guts and lungs and throats hanging out. Night: The family is a lie, a trap, and romantic love is empty, immature sentimentality. Dawn: Consumerism can take over your life until you don’t care what you buy, just that you buy, or even just look at what you could buy. Day: The government and military don’t care a whit about you, either. Land: When the crushed masses finally rebel against capitalist exploitation, if you have half a brain and heart left, you’ll root for them even as they pull the whole rotten world down with them. Diary: The media will entertain you to death – you’ll even be entertained by your death. Survival: Poignantly back to the anti-family message he started with.”

The connections between Romero’s “anti-modern” angst and classical theology led Paffenroth to write Gospel of the Living Dead: George Romero’s Visions of Hell on Earth. In the book’s introduction, he notes that what makes zombies different from vampires or werewolves is that they’re “more fully and disconcertingly human.” They may lack the power of those other monsters, but their quasi-human nature makes them harder to identify, understand, or distance ourselves from, and therefore more horrible to confront. One character in Dawn of the Dead (1978) sums it up saying: “They’re us!”

This introduces a two-tiered horror into the picture. The first is the “subtly and insidiously horrible” experience of watching survivors slaughter monsters that resemble average people. But the second – which might be even more horrible, and more subtly so – is watching the survivors begin to resemble monsters. Part of the power of Night of the Living Dead, Paffenroth argues, is that “the threat is as much within the house as without.” Outside the door are flesh-eating corpses who never stop feasting; inside, fear-driven survivors who never stop conniving. “Either way,” he writes, “people are doomed to a shadowy, trapped, borderline existence that resembles hell. It is probably no surprise, then, that much of the imagery of zombie movies is borrowed, consciously or unconsciously, from Dante’s Inferno.”

But as with Dante, Romero’s wild parade of gore and grotesqueries reintroduces us to a basic truth about human life. The zombies are slaves to mindless gluttony, rage, and sloth, while the survivors ironically embody even more deadly sins, developing “more exotic and evil desires” like cruelty and treachery. On both sides of the door, Romero holds a funhouse mirror up to our own frailty and disorder. “What the film does, essentially, is present a scenario … that takes the idea of original sin seriously, showing how depraved, violent, and predatory people would be to one another if they really were fundamentally sinful.”

Romero, who was raised Catholic but later distanced himself from his faith, doesn’t follow Dante into Purgatory (much less Paradise), but neither does he succumb to nihilism and abandon hope. “There are always survivors – broken, alone, devastated, but somehow going on,” Paffenroth observes. “It is the oddest kind of optimism, and I’ve compared it many times to the end of Shakespeare’s King Lear, the bleakest of his tragedies, but one where I’m not the only one to sense a glimmer of a hint of the possibility of there being something more and better, that things have been painfully and bloodily blown apart, but they had to be, to get rid of the rot and the blindness and disease that otherwise would’ve gone undiagnosed and unchecked.”

Dr. Paffenroth remembers Romero as many fans remember him: as a friendly, generous man who would “talk to every fan at length and show real concern for them” at horror conventions. But for the professor, Romero was something more than a great man or even a great artist. He was a great ally, a spiritual guide who has a lot to teach us about the world – including the world within.

“If I rewrote The Divine Comedy with me as Dante,” Paffenroth concludes, “he would be my Virgil.”