The art world produced its first celebrated female painters here, commissioned and supported by the Church.

Lenten Campaign 2025

This content is free of charge, as are all our articles.

Support us with a donation that is tax-deductible and enable us to continue to reach millions of readers.

On the 500th anniversary of the Protestant Reformation, this series of articles looks at how the Church responded to this turbulent age by finding an artistic voice to proclaim Truth through Beauty. Each column looks at how art was designed to confront a challenge raised by the Reformation with the soothing and persuasive voice of art.

This may come as a surprise, given that many Protestant churches have championed women’s ordination, but the first phase of the Reformation was not particularly good to women. The elimination of Mary’s role as supreme intercessor, the abolition of women’s religious orders (indeed Martin Luther had married a nun), and the rejection of the female martyrs of the Paleo-Christian era as mere legends and fantasies left women of the age without role models or guides in the complicated waters of late Renaissance society.

Furthermore, several of the Protestant leaders saw women as unfit for any kind of leadership. John Calvin wrote that women ought to be subject to men for two reasons, “because not only did God enact this law at the beginning, but He also inflicted it as a punishment on the woman.” German painter Lucas Cranach the Elder, a close friend of Luther, depicted women as sly, provocative and simpering, with a sidelong glance—whether when offering Adam the forbidden fruit or seducing a foolish old husband. These ideas were certainly not limited to the Reformers, but the Protestants lacked a repertoire of beautiful and holy women to temper the harsher view of woman as weak temptress or to develop a more nuanced appreciation for the role of women.

The Catholic Church had the advantage of centuries of Marian veneration and a liturgical calendar filled with heroic, holy women, and also knew, much like advertisers today, that nothing sells better than a beautiful woman. Women in the Church found a new impetus in the Counter-Reformation, especially in the extraordinary lives of people like St. Teresa of Avila, who reformed the Carmelite religious and wrote powerfully about her experiences, or the extraordinary Vicaress Pernette de Montluel of the Poor Clares, who courageously contested the reformers in Geneva as recorded in Jeanne de Jussie’s The Short Chronicle.

Depictions of women — created by women — flourished in this age, not only as heroines, but also showing women new ways that they could use their unique gifts to spread the Gospel.

Images of formidable Old Testament women proliferated in the Counter Reformation, from Judith slaying Holofernes to Susanna defying the lecherous elders, while Mary Magdalene became the model par excellence of conversion and repentance. The rediscovery of the bodies of St. Cecilia and St. Agnes in the newly excavated catacombs reignited the devotion to the bravery of the virgin martyrs.

The devotion to St. Catherine of Alexandria, however, enjoyed a particularly significant renewal during this period.

The 5th-century saint was a well-educated Christian aristocrat, who was sent as an envoy to the Roman Emperor to protest the persecution of the Church. Beautiful as well as wise, Catherine suffered under Emperor Maximin’s attempts first to seduce her, offering her the role of “second wife,” and then, upon her refusal, to break her through a grueling interrogation before 50 of his most erudite philosophers. Catherine converted them all with her reasoned arguments for the truth of Christianity and was thereupon sentenced to death. The spiked wheel devised for her torture (ubiquitous in her iconography and lending its name to a firework) was destroyed by angels before being used, so Catherine was swiftly beheaded and her body carried off by angels to Mt. Sinai.

Counter-Reformation artists were inundated with commissions for images of this saint, the patroness of philosophy. Where Luther had claimed, “No gown worse becomes a woman than the desire to be wise,” this lovely woman had gained Heaven not only for herself but for all seekers of truth that came into contact with her. Caravaggio painted her in contemporary dress, with a fair but familiar face, as if one might run into this heroic paragon of wisdom on the street. The 1,300-year-old saint was given a new look for the modern age that had disdained reason and embraced salvation through faith alone.

Catherine became the poster child for the art of philosophy. Despite the fact that the Acts recounting her life were riddled with inaccuracies and lacking in evidence, Cesare Baronio, the Cardinal entrusted by Pope Clement VIII to purge the martyrology of saints whose lives could be held up to Protestant ridicule as mere myth or legend, left her memorial in the Breviary as a prominent feast. As Luther denigrated philosophy, Aristotle and St. Thomas Aquinas, so the Catholic Church responded by putting forth a lovely woman of privilege who persuaded not with her physical or material attractions but with her utter command of reason and truth.

Catherine also became the frontwoman for religious sisters. The Reformers closed convents, casting women adrift into the world. In rejecting the Emperor’s suit, Catherine claimed “Christ has taken me to Himself as a bride; I have joined myself to Him as a bride in an indissoluble bond.” This mystical marriage, never mentioned in her Acts, became a preferred subject of the Counter Reform.

Annibale Carracci painted this version in 1587 for the wealthy Farnese family. Although many artists tackled the subject, including Guercino, Ludovico Carracci, Albani and Cavorozzi, Annibale added a romantic flourish, as charming as any love story. Like Romeo and Juliet, wedded at night, this intimate marriage emerges as light out of darkness. Soft blush and rose tones frame the radiant wedding party. Catherine, regally dressed in gold and mulberry, gazes downwards like a modest bride as she proffers her long elegant fingers towards Christ. The luminous child gently caresses her hand while embracing His mother, uniting the virgin princess and the Blessed Virgin. The angel drawing the betrothed together forms a shimmering golden backdrop for the scene, but the red sashes that cross his chest allude to the fact that this love, sealed today with a ring, will be consummated in blood when she follows Christ to martyrdom. Try as it might, Hollywood has never produced a love story as compelling as this.

In the Counter Reformation, women were not only exalted after their death as saints, but there was also room for women to lead in society. Beyond the stateswomen such as Mary Tudor of England and Mary of Scots, Catherine de’ Medici and Jeanne d’Albret, St. Angela Merici founded the Ursulines to offer solid Christian education for girls and young women, Victoria Colonna composed renowned poetry and debated theology, and art produced its first celebrated female painters.

On one hand, technological advances had opened the door for women painters. Oil painting permitted women to work alone (not with a team of male fresco artists) in an inexpensive and slow-drying medium. The Catholic Church, however, was looking for new ways to evangelize through art and was unafraid to give women a chance. Sofonisba Anguissola, Elisabetta Sirani and Artemisia Gentileschi all had very successful careers working for both private and ecclesiastical patrons, but it was Lavinia Fontana who would burst the canvas ceiling when she was commissioned to produce the first Italian altarpiece to be painted by a woman.

Her patron was none other than the powerful Gabriele Paleotti, who had recently published the Discourses On Sacred and Profane Images in 1582. As an expert in art and decorum, this Cardinal, friend to St. Charles Borromeo, catapulted Lavinia’s career to stratospheric success.

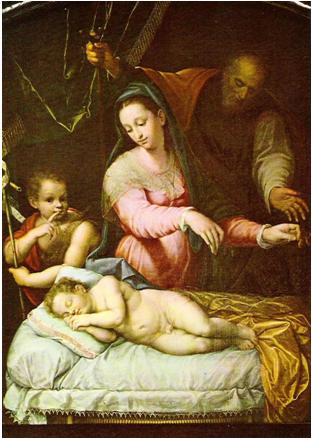

Her first altarpiece was Christ in the house of Mary and Martha, executed in 1580, but her style soon matured and she was asked to produce two altarpieces in the most male-dominated art town in Italy: Rome. Her work for St. Paul Outside the Walls is lost, but her St. Hyacinth is still visible in its chapel in the church of Santa Sabina. Her most prestigious commission (which yielded as much in commission as a Caravaggio work) was for Phillip II of Spain, who had heard about this extraordinary woman and requested The Sleeping Christ Child.

This work brought Lavinia’s delicate brushwork together with her strong draftsmanship, especially when depicting small children, a notoriously difficult subject. Jesus sleeps peacefully on a platform swathed in white linen and gold silk reminiscent of an altar. Mary gently covers her Son with a transparent cloth, evoking both the shroud and the humeral veil. For his part, Joseph forms a protective space around her, and hold his staff upright behind her. He offers stability and security in this world as Christ offers light and peace in the next. The infant John the Baptist holds his reed cross at Jesus’ head while playfully reminding us not to disturb his cousin’s tranquil slumber.

An image foreshadowing Christ’s eventual death to redeem mankind, the work is also a picture of a fulfilled, serene and happy wife and mother.

Married happily to Paolo Zappi, with whom she had 11 children — and who occasionally painted backgrounds for her when she was overwhelmed with work — Lavinia gave women a role model that resonates beyond the 16th century to today – material success, happy marriage and deep faith, the Counter Reformation model of feminine genius.