This truth of our faith is not easy to visualize, but artists through the centuries have brought their skills to their devotion.

Lenten Campaign 2025

This content is free of charge, as are all our articles.

Support us with a donation that is tax-deductible and enable us to continue to reach millions of readers.

When you think of the Blessed Trinity, what image comes to mind?

This central truth of our Christian faith – that God is one God in three divine Persons, Father, Son, and Holy Spirit – is not the easiest doctrine to put into words, never mind visualize. Most of us fall back on abstract symbols: the Sign of the Cross we learned to make as children, the first time we invoked the Trinity in prayer; the equilateral triangle; St. Patrick’s trusty shamrock.

These, along with the Celtic triquetra (or “cornered circle”) with its three interlocking pointed ovals, are all excellent and time-tested symbols that serve as shorthand for a deep mystery.

Our belief in the Blessed Trinity, however, is more than an abstract theological idea. The Trinity is a relationship – the most intimate of all relationships, the union in love that brings forth and redeems and transforms all creation – and our faith in the Trinity is relational, too.

That is why, despite the difficulties presented in depicting the Oneness of Three, artists through the centuries have attempted to depict the Blessed Trinity in devotional art that draws on the conventions of flesh and blood, the incarnate world. All such images, of course, like all our words, fall short of the fullness of the mystery, the Beatific Vision that is reserved for the blessed in heaven.

But in celebrating the Solemnity of the Most Holy Trinity, it is worth exploring some of these images prayerfully. Here are a few to linger with:

One of the earliest images of the Blessed Trinity in Christian art features three nearly identical persons. Carved on a 4th-century sarcophagus, this “teaching image” depicts the Three Persons of the Trinity in the act of creating Eve. Father, Son, and Holy Spirit are not yet distinguished by identifying characteristics but are closely joined in the composition.

The Eastern Church continues the tradition of depicting the Trinity as figures similar in age and facial features, but introduces symbolic differences indicated by color and position. This icon by the great Andrei Rublev draws on the tradition that the 3 angels who visit Abraham and Sarah with the news of Isaac’s miraculous conception (Genesis 18) prefigure the Blessed Trinity.

Most scholars identify the angel on the left with the Father. He wears a gold robe of majesty over the blue of divinity and is blessing the cup that contains the head of the sacrificed calf. Above the Father is a house, symbolizing the “Father’s house” of heaven. The angel in the center depicts the Son. He wears a red robe of humanity with the blue cloak of divinity over it and holds his right hand in the gesture that signifies Christ’s dual nature. Above him is the oak tree of Mamre, where Abraham’s tent was pitched, which signifies the wood of the cross. The angel at the right is identified with the Holy Spirit. He wears a blue robe of spirituality with a green cloak symbolizing hope. Above his head are mountains, symbolizing the ascent of the soul the Spirit inspires.

All three Persons are seated at the same level, indicating their equality, but the Son and the Spirit bow their heads in the direction of the Father.

In the West, especially after the Reformation, depictions of the Trinity began to distinguish among the Persons of the Trinity. The Father was identified by age, with a white beard, and by his enthronement as a king or emperor. In this depiction by Lucas Cranach, the Father holds the globe of empire and wears the triple tiara usually associated with the pope. The Son becomes personified by his incarnation in Jesus Christ – often, as here, shown on the cross. The Holy Spirit is no longer depicted in human form but as a dove, as in Scripture. The Trinity is often shown enclosed in an almond-shaped halo (mandorla), here formed by worshiping angels.

Depictions of the Trinity that emphasize the crucifixion – showing Christ crucified in the arms or lap of the imperial Father, with the dove of the Spirit hovering above – are sometimes known as The Mercy Seat.

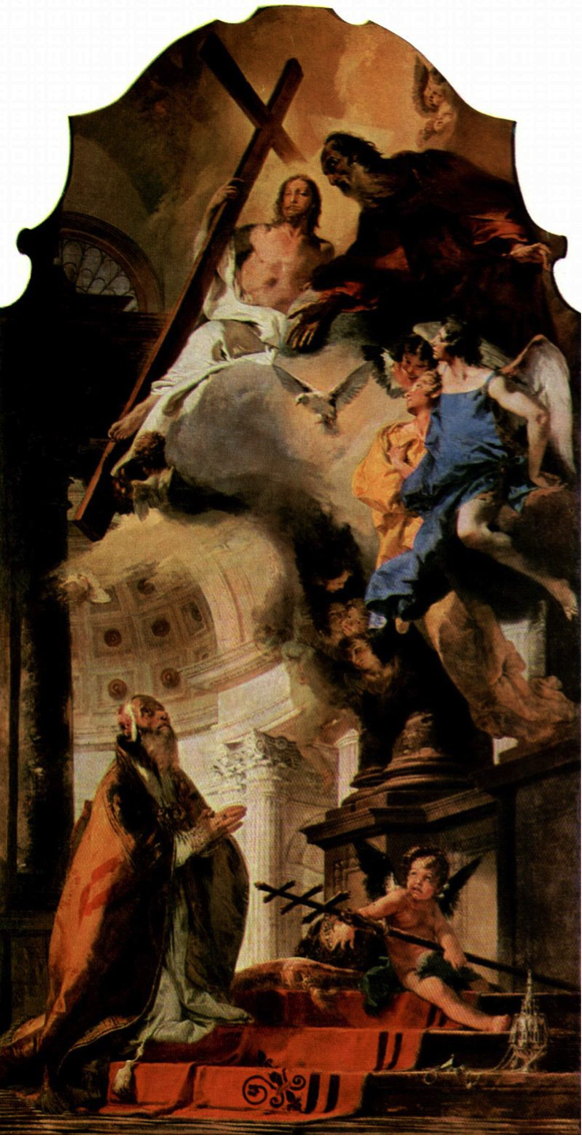

Counter-Reformation Catholic artists like Tiepolo also stressed the centrality of redemption in their depictions of the Blessed Trinity. In contrast to Protestant artists, however, they stressed the link between the One God and Christ’s True Presence in the Blessed Sacrament. Here Tiepolo depicts St. Clement of Rome, the third pope, kneeling before a Eucharistic altar over which the Trinity appears. An angel holds Clement’s papal triple cross, and he has set down the keys of the kingdom next to the incense burner on the altar steps.

In this charming representation, Murillo links the Blessed Trinity in heaven with the Holy Family on earth in the Person of Jesus. Murillo reflects the Trinity and the Holy Family as models of loving relationship for all Christians. The Father in heaven holds the globe of power but wears no imperial trappings. The Holy Spirit in the form of a dove hovers over the young Jesus, whose halo symbolizes his divine nature. Mary looks to her Son, and Joseph looks to us as though inviting us into the family of God’s love.

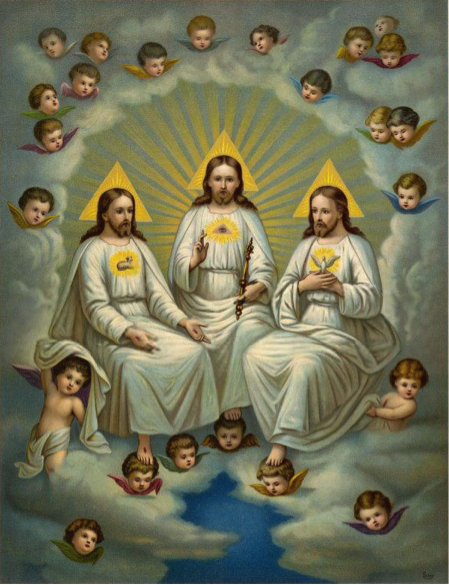

In an unusual departure (even for the artist, who produced many other images of the Trinity employing standard Western iconography), illustrator Fridolin Lieber returned to the early Eastern representations of the Blessed Trinity for this print, although this particular model, known as the “Triplet Trinity,” was forbidden by pope Urban VIII, and most of the representations of the Trinity that followed this model were actually repainted during the XVII and XVIII century. Lieber, who made posters for use in Christian religious education, here depicts the Persons of the Trinity as three men identical in age, wearing identical white robes and each depicted with a halo formed by an equilateral triangle.

Lieber has included identifying characteristics, however, drawn from symbolic iconography. The Father, in the center, holds the scepter of sovereignty, and bears on his chest the image of the Eye of Providence, an eye within a triangle that symbolizes the Father’s eternal watchfulness. The Son, on the left, bears the wounds of the crucified Christ, and on his breast is the image of the Lamb of God. The Holy Spirit, on the right, has his hands folded in prayer and wears the symbol of the dove.

If you were an artist commissioned to depict the Blessed Trinity, how would you choose to portray this mystery of faith?