Medieval illuminated texts belonging to three monotheistic religions will be on exhibit until February 2019.

Lenten Campaign 2025

This content is free of charge, as are all our articles.

Support us with a donation that is tax-deductible and enable us to continue to reach millions of readers.

The three monotheistic religions have a few things in common: the belief in a singular God, the notion of Abraham as a founding patriarch and the primacy of the written word to convey God’s message—this is why believers of the three faiths are sometimes called “people of the book.”

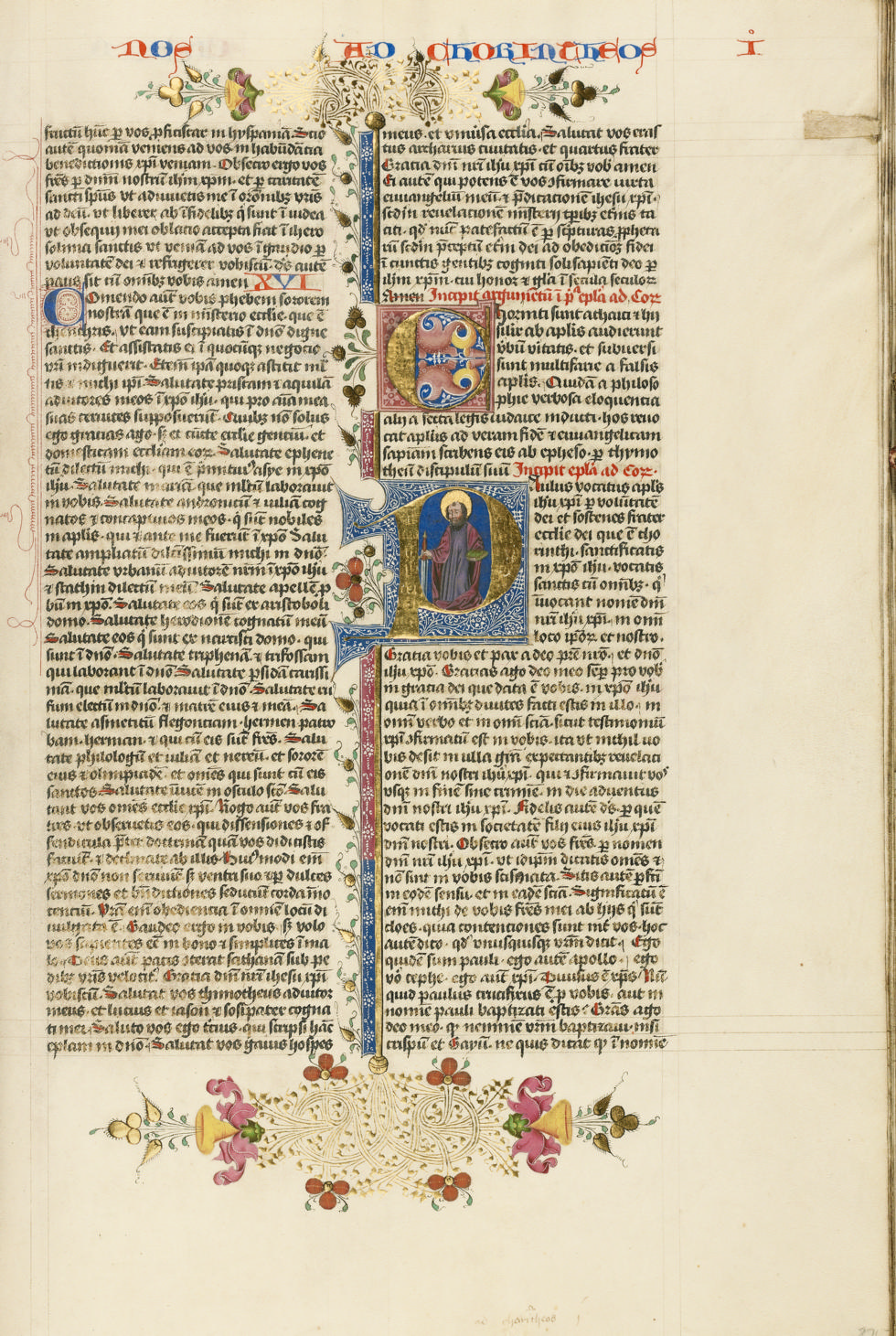

A new exhibition at the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles will explore this last commonality by showcasing an impressive collection of beautiful illuminated manuscripts from medieval copies of the Torah, the Bible, and the Qur’an. Titled “Art of Three Faiths: A Torah, A Bible, and A Qur’an,” it is the first exhibition held at the Getty where medieval manuscripts from all three monotheistic religions will be exhibited at the same time.

During the Middle Ages, most manuscripts were written on parchment, usually made from the prepared hide of a calf, goat or sheep. Important volumes, such as the scriptures and the prayerbooks of wealthy families, were decorated with illustrations or designs made of glowing gold leaf and luminous colors—a technique referred to as “illumination.”

The first illuminated copies of the Torah appeared around the mid-13th century. Since many European feudal states had laws preventing Jews from joining painting guilds, the artwork decorating pages of the Torah was often drawn by itinerant Jewish scribes and illuminated by local—and sometime Christian—artists. The J. Paul Getty Museum recently acquired a medieval copy of the Torah, known as the Rothschild Pentateuch, dating to 1296. The rare manuscript features one of the richest collections of illuminations in Jewish art, including three full-page paintings, more than a hundred illuminated text panels and hundreds of marginal images featuring fantastic creatures and abstract motifs. (Orthodox Judaism prohibited the depiction of the human image.) Experts believe that it was created in either Germany or France by or for a Jewish family that escaped from England, from which Jews were expelled in 1290.

Islamic scripture has a rich history of illumination, too. During the early days of Islam, scripture was mostly transmitted through oral tradition, but from the late 7th century the Quran started to be recorded in beautiful Arabic calligraphy, often following an angular style known as kufic, which sought to create geometrical harmony within the written text.

By the 8th century Islam had spread from the Iberian peninsula to northern Africa and into Central and Eastern Asia, marking the start of the Islamic Golden Age, a period of economic, scientific and cultural growth. And that’s also when scripture started to feature luminous illuminations. These were elaborate patterns of geometric and floral design, as Islam too prohibits the depiction of the human form. The lettering itself became the art. Decorative artists were held in great esteem in the Islamic word and their names would often feature—as a beautiful illumination—in manuscripts’ colophons. Sometimes, manuscript owners would even ask “celebrity” artist to agree to have their name featured in the text—even if they were not the original calligrapher.

The copy of the Quran featured in the exhibition is a 9th-century North African Qur’an probably created in what is now Tunisia.

Christian Bibles were among the first texts to feature illuminations when the art came into being. Bibles written in Greek, Latin, Syriac, Ge’ez, Armenian and other languages often came with gorgeous illustrated, ornate capital letters at the start of paragraphs, page margins or full page text illustrations. One of the most important examples of illuminated Bibles is the Book of Kells, a Gospel book written in Latin created in a Columban monastery in the British Isles around the year 800, regarded as pinnacle of illumination from the area and as Ireland’s finest national treasure.

The Christian Bible featured in the Getty exhibition is a 15th-century manuscript created by the Stefan Lochner, a Northern Renaissance painter known for his innovative technique that featured detailed landscapes and voluminous figures.

”The three objects on display are exceptionally beautiful artworks that we hope will spark meaningful dialogue among various audiences,” said Elizabeth Morrison, Senior Curator of Manuscripts at the Getty Museum. “Museums offer more than simply an aesthetic experience. Through exhibitions such as this one, they foster a deeper understanding of history that helps us to reflect on our own shared experiences.”

The exhibition was curated by Kristen Collins, Bryan Keene, and Elizabeth Morrison of the Department of Manuscripts at the J. Paul Getty Museum and will be ongoing until February 3, 2019.