Built by a Portuguese King in 1747, the Holy Chapel of St. John the Baptist is one of the first examples of “prefab” architecture.

Lenten Campaign 2025

This content is free of charge, as are all our articles.

Support us with a donation that is tax-deductible and enable us to continue to reach millions of readers.

King João V, also known as “the Magnanimous” and the “Portuguese Sun King,” ruled Portugal between 1706 and 1750, at a time when the country’s colonial empire was flourishing. Thanks to a tax on gold that was imposed on minerals extracted in colonial lands, especially in modern-day Brazil, the king could rely on a constant source of income. He spent much of this to finance ambitious architectural projects such as the massive National Palace in Mafra, a few miles out of Lisbon, consisting of a palace, a basilica, a convent and a hunting reserve.

So when in 1742 the “Portuguese Sun King” decided to build a chapel in honor of St. John the Baptist, he asked for the best craftsmen in Europe to take part in the project. But instead of asking architects and sculptors to travel to Lisbon, King João ordered what is probably one of the first instances of “prefabricated” real estate projects in history.

The Chapel of St. John the Baptist, located inside the Church of São Roque in central Lisbon, was in fact designed and constructed in Rome by Nicola Salvi, an Italian architect famous for designing the Trevi Fountain, and Luigi Vanvitelli, the most prominent Italian engineer of the 18th century. After four years of intense work, the chapel was disassembled into separate components, shipped to Lisbon in three boats and re-assembled inside the Church of São Roque—a process that made it the most expensive chapel built in Europe at the time.

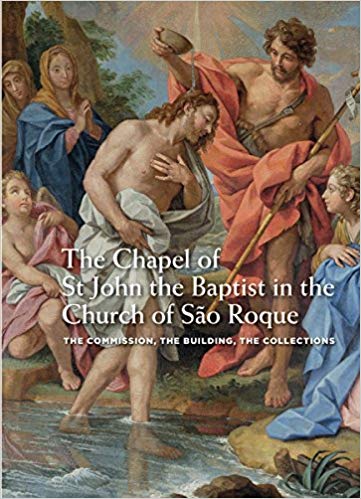

Featuring lavishly ornamented floors in colored marble and columns with straight channeled shafts, the chapel introduced the “Roman Baroque” or “rococo” style—characterized by the rich use of ornaments and fluid curves—into Portugal. King João demanded the finest materials to be used for ornaments, such as Carrara marble, amethyst, lapis lazuli and agate stone. The chapel interior decorations feature a panel made of three elaborately decorated mosaics: The Baptism of Christ, located at the center, and the Annunciation and Pentecost, located on on the sides of the panel.

The intricate mosaics are made of tiny tessellae as little as 0.1 inches—all of which had to be taken apart and carefully placed back together under the supervision of Manuel Pereira de Sampaio, the Portuguese ambassador to the Holy See. Indeed, the process took so long that two of the panels, The Baptism of Christ and Pentecost, were reassembled in 1752, two years after the death of King João.

And now, a new book by Teresa Leonor M. Vale, a Professor of Art History at Lisbon University, is offering the first comprehensive reconstruction of the entire process—commissioning, execution and delivery—that brought this ambitious architectural project to life. Together with her team of Portuguese and Italian co-authors, Vale explored the role of colonial taxes in the project’s financing, the recruiting of some of the most important artists and craftsmen of the era and some previously little known facts such as the role played by the sister of a Roman cardinal, Maria Anna Cenci Bolognetti, who oversaw the entire production of embroidering for the project—a remarkable responsibility for a woman at the time.

The authors also explore the personal meaning that the Chapel had for its commissioner. Part of what pushed King João to undertake such a colossal project was the desire to create an architectural symbol of the reconciliation with Pope Benedict XIV, with whom the ruler had a disagreement about the ordination of bishops of Lisbon some 20 years before.

Research for the book, titled The Chapel of St John the Baptist in the Church of São Roque: The Commission, the Building, the Collection (Scala Arts and Heritage Publishers, 2017), was made possible thanks to extensive restoration work started in 2006 that allowed experts to study the artifacts up close for the first time.