Many theories have arisen, but we may never know for sure.In the late 12th century there was a chronicler at Christ Church in Canterbury named Gervase. Aside from matters related to his office, relatively little is known of this monk’s life; he is often confused with one of several other of Gervases of the same era. It is in brother Gervase of Canterbury’s records, however, that can be found one of the most curious passages in the annals of the old English Cathedral city.

The records states that five monks reported a strange sight to Gervase shortly after sunset on the night of June 18, 1178:

They saw “the upper horn [of the moon] split in two.” Furthermore, Gervase writes, “From the midpoint of the division a flaming torch sprang up, spewing out, over a considerable distance, fire, hot coals and sparks. Meanwhile the body of the Moon which was below writhed, as it were in anxiety, and to put it in the words of those who reported it to me and saw it with their own eyes, the Moon throbbed like a wounded snake. Afterwards it resumed its proper state. This phenomenon was repeated a dozen times or more, the flame assuming various twisting shapes at random and then returning to normal. Then, after these transformations, the Moon from horn to horn, that is along its whole length, took on a blackish appearance.”

It is unclear if the monks believed this to be a mystical vision, or if there was any deeper meaning attributed to what they had seen. There is no further mention of these events in Canterbury records. The story, however, has baffled astronomers and scientists who have many theories as to what caused this unique and seemingly isolated sighting.

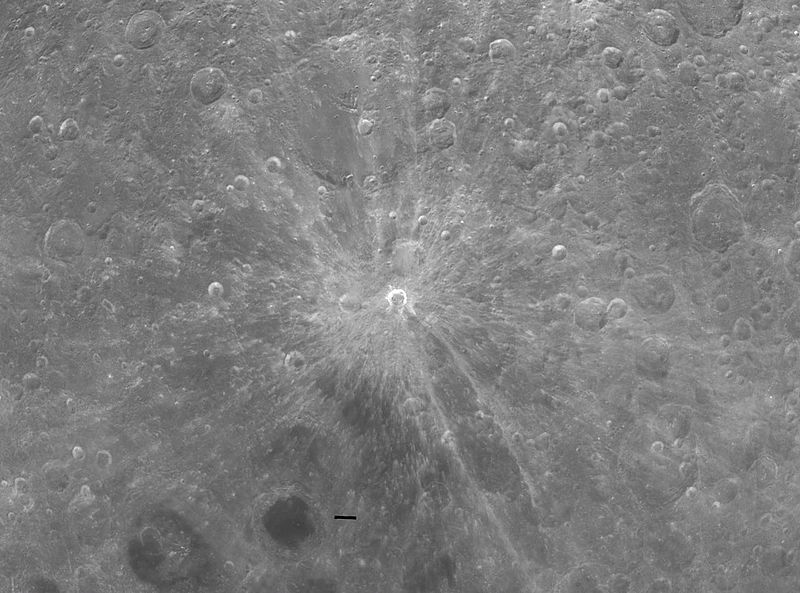

In 1976, geologist Jack B. Hartung proprosed that the description closely resembled what would have been seen during the formation of the crater known as Giordano Bruno, a relatively new crater as far as the moon’s timeline goes.

We can tell that Giordano Bruno is new from the vivid ray system — lines formed by debris upon meteorite impact — that is still apparent today.

Given that the moon is often hit by micro-meteorites, which kick up dust and cover these lines, we can tell that the Giordano Bruno crater was formed at some point during human history and it is not outside the relm of possibility that this crater was formed in 1178.

There are, however, holes pock-marking this theory. The creation of a crater as large as Giordano Bruno would kick up enough debris to make a week-long meteor storm clearly visible around the world. Yet no such records exist in any of the era’s most prominent astronomical cultures, including European, Chinese, Arabic, Japanese and Korean.

In 2001, Paul Withers of the University of Arizona Lunar and Planetary Laboratory proposed a new theory:

“I think they happened to be at the right place at the right time to look up in the sky and see a meteor that was directly in front of the moon, coming straight towards them,” Withers said. This idea was strongly suggested by others in a 1977 scientific paper.

“And it was a pretty spectacular meteor that burst into flames in the Earth’s atmosphere — fizzling, bubbling, and spluttering. If you were in the right one-to-two kilometer patch on Earth’s surface, you’d get the perfect geometry,” he said. “That would explain why only five people are recorded to have seen it.”

It is of course, impossible to prove this theory, or any theory as to what the five Canterbury monks saw. It seems just as likely that the monks witnessed a mystical vision as it would that a meteorite caught their eye at just the right angle, at just the right time.

It is, perhaps, relevant that while the monks used horns and snakes to describe the scene, they never equated it to a passage from the Bible, or claimed it to be any more than what they saw. On the other hand, it is also quite possible that Gervase of Canterbury only recorded the facts of what the monks saw, rather than their speculations on what it might have been.