As Augustine wrote, “He who sings prays twice.”

Lenten Campaign 2025

This content is free of charge, as are all our articles.

Support us with a donation that is tax-deductible and enable us to continue to reach millions of readers.

For nearly two millennia, the Catholic Church has worked to develop music and its notation from its origins in chant right up to and through the limitless beauty of polyphony. Music helps to enhance our prayers so that we may better glorify God, which makes sense considering the angels are commonly depicted as singing in a choir to praise their maker.

To this end, countless composers have devoted their lives to writing sacred music, but they learned early on that they would need a way to disseminate their tunes. Thus musical notation was born, allowing for the widespread performance of hymns that would otherwise be trapped in the cathedral or monastery where the composer was stationed.

The inception of sheet music opened the door for all members of the universal Church to sing the same hymns, but it brought with it the difficulty of training singers to read the neumatic notation. While this early form of musical notation was simple, it left out things like tempo, dynamics, and note duration. Neumatic notation was open to the interpretation of the singers, and thus it was rarely performed exactly the same by two different choirs.

It was in the early 11th century that Guido of Arezzo, an Italian Benedictine monk and music theorist, began to work on developing a method for teaching the singers to learn chants in a short time. This method was most likely the Guidonian hand, a mnemonic system where note names are mapped to parts of the human hand. Although sources suggest Guido was not the original designer of the system, his work popularizing the hand led to his name’s attachment to it.

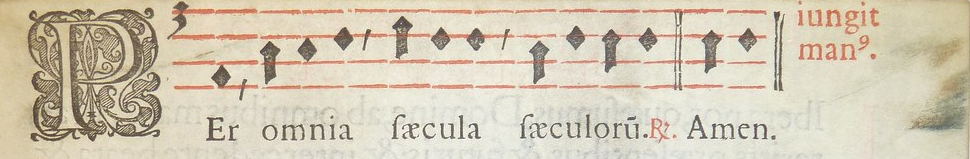

Guido’s musical work, along with some hostility from some of the monks at his abbey due to his popularity, led to the music theorist to take a station at Arezzo to train singers at the cathedral. There, Guido revolutionized medieval music by developing staff notation, or the modern form of written music.

The staff organized the notes into a concise bar, which made it easier to match notes to their lyrics and identify their pitch or duration. With the staff, Guido identified hexachords, which is where things got more complicated. Hexachords are a grouping of six notes, originating from one of three pitches: G, C, and F. In laymen’s terms, the hexachord is what would eventually evolve into the musical scale.

Ironically, hexachords are confusing for the very reason they were meant to simplify the music learning process. While two hexachords may start on different notes, the singer was meant to focus more on the intervals between the notes than the actual names of the notes themselves. These note names were a bit more complex than our current method of notation, which labels notes A-G and repeats when going up or down an octave.

Guido identified that he needed one more step to help teach his students, and so he developed solmization, or as we know it today, solfège. Solmization labeled each interval in the hexachord from bottom to top with the syllables “ut–re–mi–fa–so–la,” taken from the first six half-lines of a hymn dedicated to St. John the Baptist, the Ut queant laxis: “UT queant laxis, RE sonare fibris, MIra gestorum, FAmuli tuorum, SOlve pollute, LAbii reatum” (“So that your servants may, with loosened voices, resound the wonders of your deeds, clean the guilt from our stained lips”).

With solmization, suddenly it no longer mattered if the hexachord began on C, G, or F, because the focus was changed to the intervals between notes, rather than the notes themselves. This became an invaluable tool for musicians to sight-read and memorize music.

Over the years solmization was tweaked a bit. Giovanni Battista Doni eventually changed the “ut” to “do” — which he took from his own last name — and a seventh interval, “si” would be added to complete the diatonic scale. However, the “si” would eventually be changed to “ti” so that each interval would start on a different letter.

Today, solfège allows singers to easily read new music by ignoring the key — aside from the tonic tone (ex: in the key of G, G is tonic) — and determining the pitch based purely on the intervals between notes. This allows singers to face music in a variety of keys with the same method.

Solfège can make one’s head spin when first learning, but as with all aspects of music, practice is the key to success. Just an hour a day could have you singing “Do-Re-Mi” with the same ease as Maria von Trapp, in The Sound of Music.