Lenten Campaign 2025

This content is free of charge, as are all our articles.

Support us with a donation that is tax-deductible and enable us to continue to reach millions of readers.

We all know California is one of the wine capitals of the world. Thanks to immigrants coming from wine-producing regions of the planet and to a favorable climate, the Golden State became the cradle of a burgeoning wine scene during the late 19th century. But the sudden introduction of prohibition rules around the sale of alcohol affected many of California’s up and coming wine producers. The Volstead Act, passed in October 1919, effectively banned the sale and consumption of any beverage that contained more than one half of one percent alcohol.

Yet, there were some notable exceptions to the ban. Alcoholic liquids used for medicinal or cosmetic purposes, such as perfumes, and those needed for religious purposes, such as sacramental wine, could be freely traded within the United States. This exemption allowed Catholics across the country to ensure sacramental wine was available for Mass. It also allowed ingenious wine producers to make a living through the Prohibition era.

As explained by Keith Wallace, the founder of Wine School of Philadelphia, in Vinepair.com, struggling producers in California started to apply for religious permits to find a market for their wine.

But applying for a permit wasn’t easy. First, wine producers had to get permission from the Bureau of Prohibition, a federal law enforcement agency tasked with enforcing the Volstead Act. Then, once the right permits were secured, winemakers had to find a religious leader to act as the manager of the winery overlooking production and distribution. The religious leader-turned-wine-manager was also tasked to make sure that the wine was going to be used for religious purposes rather than general consumption.

Despite the red tape, production of holy wine in California started to boom. “Grape production in heavily Roman Catholic California increased by 700 percent during Prohibition,” writes Gregory Elder, professor of history and humanities at Moreno Valley College and a Roman Catholic priest.

Yet, demand for sacramental wine did not change during that time. The Precious Blood was only consumed by the clergy during Holy Mass. It wasn’t until the 1960s, after the Second Vatican Council, that Communion under both species, Body and Blood, was opened up to the congregation.

This mismatch in supply and demand suggests that many church leaders essentially stepped in to help struggling winemakers to avoid bankruptcy by boosting demand for holy wine. Some church members allegedly became bootleggers, selling “holy wine” on the black market.

Church warehouses soon became the only place where large quantities of wine could be found. Parishes thus became the target of wine thieves, who would break in and steal the precious banned liquor to sell it on the black market. They were also the target of investigations by Prohibition authorities. In 1925, the Department of Research and Education of the Federal Council of the Churches of Christ reported that nearly three million gallons of wine labeled as sacramental use had been seized by authorities investigating illegal alcohol trade.

San Antonio saved

One of the most famous wineries that was “saved” by holy wine production during the Prohibition is Los Angeles’ San Antonio Winery, which is still a leading producer of sacramental wine to this day.

In 1917, when San Antonio Winery was founded by Santo Cambianica, an Italian immigrant and devout Catholic, there were about 90 wineries in the Los Angeles area. After the Prohibition, only six wineries were still standing.

What saved San Antonio Winery was a quick shift to holy wine making production. As soon as the Volstead Act came into effect, the winery struck a deal with the local church and became the official supplier of sacramental wine. As explained in Smithsonian magazine, the deal was aided by the fact that the winery was named after a Catholic saint and that Cambianica himself was a devout Catholic with strong ties to the local parish. San Antonio “was a faith-based company,” says Steve Riboli, vice president of San Antonio Winery and great-nephew of the founder. “Literally.”

In the end, Cambianica’s shift to holy wine production proved more than an emergency tactic. The pivot-to-sacramental wine helped the winery grow during the Prohibition. According to the Smithsonian magazine report, San Antonio winery was making about 5,000 cases of red wine before 1919. When the alcohol ban was finally lifted in 1933, it was producing as many as 20,000 cases.

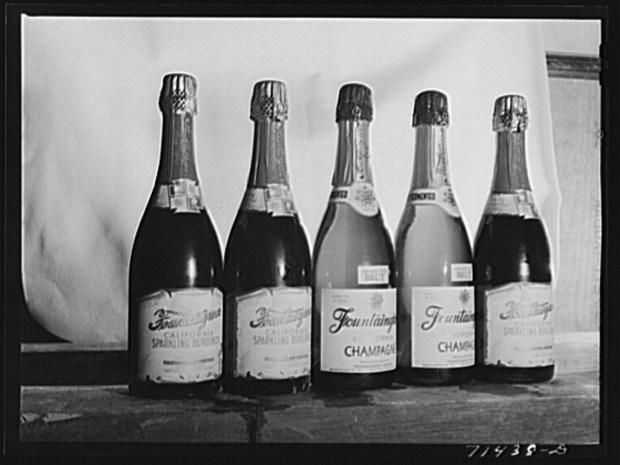

Today, the sacramental wine market accounts for less than a half of one percent of all wine sold in the U.S. But if it hadn’t been for sacramental wine, many historic wineries like San Antonio would not have survived the 14-year Prohibition era. Indeed, holy wine making still informs the winery strategy today, as San Antonio is the largest supplier of sacramental wine in the U.S., producing a range of six wines including a red, a rosé, a light Muscat and an Angelica.

San Antonio winery is also considered a cultural landmark in Los Angeles as the last winery to be based within the city. If it hadn't been for its founder’s decision to expand into sacramental wine, it probably would not be here at all.