Lenten Campaign 2025

This content is free of charge, as are all our articles.

Support us with a donation that is tax-deductible and enable us to continue to reach millions of readers.

Science is central to modern life. It is because of science that you are reading Aleteia on a screen, via the internet, not on paper, by the light of an oil lamp. This series of articles (click here for the whole series) dives deep into the story of the Catholic Church and science. The story goes back a long way. It is still unfolding today. It is not the story you might think you know. But it is a story you should know, exactly because science is so central to modern life.

~

What about the case of Galileo? In the previous post in this series, we saw how much concern there was within the Church regarding the scientific problems with the theory of evolution. We also saw concern regarding revising religious thought for the sake of theories that might not withstand the test of time.

Was that what was happening in the Galileo case?

There is less information available about the Galileo case than the evolution case, but it seems likely that the answer to this question is “yes.”

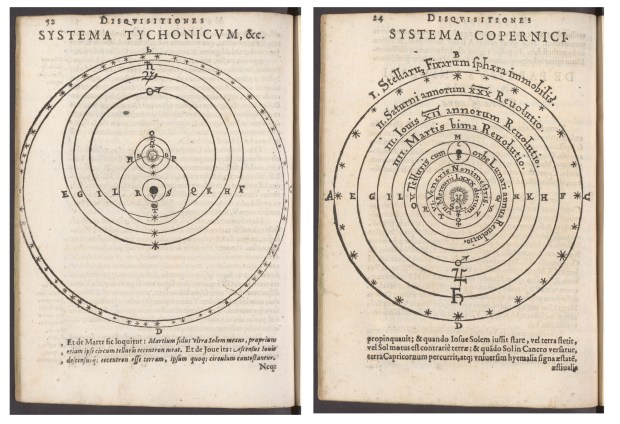

You will find it said in many places that Galileo proved Nicolaus Copernicus’s “heliocentrism,” the idea that the Earth circles the sun. That is not true. Heliocentrism was hard to prove. Earth’s motion around the sun was not so easily verified as Ptolemy’s claim that the stars were larger than the moon, contrary to the “two great lights” of Genesis (see Part 1 in this series).

Those who opposed Galileo focused on a problem involving the sizes of stars in a Copernican universe — in essence, on a variant of the “great lights” question. Ptolemy discussed how the appearance of the stars is independent of the place on Earth from which they are observed, with the result that stars must be far larger than the Earth (and the moon). That logic, when applied to a moving Earth, where the appearance of the stars becomes independent of the place on Earth’s orbit from which they are observed, results in stars being far larger than Earth’s orbit. If Copernicus was right, stars would all utterly dwarf the sun.

This was first pointed out around the turn of the 17th century by the astronomer Tycho Brahe. He also produced a new Earth-centered model for the universe that, some years later, turned out to be fully compatible with new telescopic discoveries of Galileo. Some Copernicans, including Johannes Kepler, simply accepted the enormous stars implied by heliocentrism. Brahe, however, said they were absurd. Brahe’s model generally retained Ptolemy’s stellar distances and sizes. It did not suffer from the star size problem.

In the first half of the 17th century, following the advent of the telescope, Jesuit astronomers such as Frs. Christoph Scheiner, Giovanni Battista Riccioli, and André Tacquet developed Brahe’s star size argument further. Scheiner and Tacquet produced brief, elegant versions of the argument (the discussion above of how Earth’s orbit in heliocentrism becomes the basis of observation as opposed to the Earth itself, is from Tacquet). Riccioli, by contrast, published large tables containing precise telescopic stellar measurements and the results of calculations made from those measurements, along with pages of discussion — and reached similar conclusions about heliocentrism and star sizes.

What this all meant was that Brahe’s star size argument, and his model, seemed to grow stronger over time. Science seemed to be backing the idea that Earth did not move. In 1674 Robert Hooke, the scientist who clashed with Isaac Newton and who did early work with microscopes, called the star size argument “a grand objection alleged by divers of the great Anti-copernicans with great vehemency and insulting; amongst which we may reckon Ricciolus and Tacquet … hoping to make it [the Copernican universe] seem so improbable, as to be rejected by all parties.”

However, by 1674 astronomers including Hooke himself had begun to publish data suggesting problems with measurements of the apparent sizes of stars. These problems indicated that such measurements wildly inflated star sizes, even when done carefully and telescopically. Nevertheless, the sizes of stars remained a difficulty for heliocentrism well into the 18th century.

Vatican investigators

The star size argument was known to some of those involved with the Vatican’s actions against heliocentrism, both in 1616 when the subject of heliocentrism was first treated by the Congregation of the Index, and in 1632-33, following publication of Galileo’s Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief Worlds Systems: Ptolemaic and Copernican. Msgr. Francesco Ingoli, who Galileo believed to have been influential in the rejection of heliocentrism by the Congregation of the Index in 1616, cited the star size argument against Copernicus in his writings. So did Fr. Melchior Inchofer, S.J. who was selected for a three-person Special Commission formed by Pope Urban VIII to investigate the publication of the Dialogue.

Star sizes were not the only scientific problem with heliocentrism. There was nothing to explain how the Earth, a sphere of rock and water of obviously vast weight, could be carried around the sun. Isaac Newton’s physics, which would explain it, lay decades in the future. By contrast, an explanation for how the sun and stars might be carried around the Earth dated all the way back to Aristotle. He simply supposed that celestial bodies were made of an ethereal substance that moved naturally. Also, heliocentrism called for a rotating Earth. Such rotation should induce deflections in the observed trajectories of projectiles and falling bodies — deflections that were not observed, as Riccioli and other Jesuits took pains to emphasize. There was, as Salvatore Brandi would later say about evolution (see Part 4 in this series), an absolute lack of scientific evidence to confirm heliocentrism.

Scientific objections and the Vatican

A full picture of the role that scientific objections played in the Vatican’s actions against heliocentrism and Galileo is not yet available. More study is needed to better understand the extent to which scientific arguments such as Brahe’s, bolstered by the work of astronomers such as Scheiner, motivated those actions. The parallels between the heliocentrism and evolution cases suggest, however, that what went on in the Galileo case in the early 17th century was similar to what went on in the evolution case in the late 19th century — when scientific questions, combined with the idea that the natural sense of biblical words should not be abandoned unless necessary, were significant considerations for the Church authorities who were trying to evaluate a complex scientific question. Why would anyone consider reinterpreting Scripture for what seemed at the time to be a weak theory?

Indeed, what would be the implications of reinterpreting Scripture for a weak theory?

NEXT: Reinterpreting Scripture without necessity.

~

This series is based on the paper “The Vatican and the Fallibility of Science”, presented by Christopher M. Graney at the “Unity & Disunity in Science” conference at the University of Notre Dame, April 4-6, 2024. The paper, which is available through ArXiv (click here), contains details and references for the interested reader.

The paper, and this Aleteia series, expands on ideas developed by Graney and Vatican Observatory Director Br. Guy Consolmagno, S.J. in their 2023 book, published by Paulist Press, When Science Goes Wrong: The Desire and Search for Truth (click here).