These profiles in courage exemplify the values to which all servicemen and women aspire.

Lenten Campaign 2025

This content is free of charge, as are all our articles.

Support us with a donation that is tax-deductible and enable us to continue to reach millions of readers.

Although they make up only 12.3 % of the U.S. population according to the Census Bureau, Black people have contributed with enormous heroism to the U.S. military. These 5 Black members of the American armed forces exemplify the courage, perseverance, and honor to which all servicemen and women aspire.

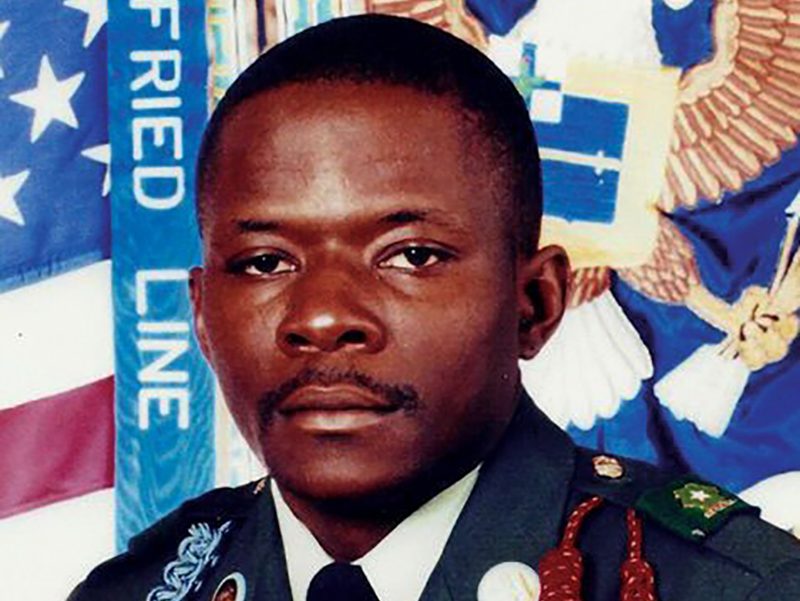

Alwyn Cashe

Sgt. 1st Class Alwyn C. Cashe was known as a “selfless, tough as nails, old school” non-commissioned officer, but his selflessness became the stuff of legend when his Bradley Fighting Vehicle was ambushed in Iraq in 2005. The vehicle struck an explosive device and caught fire, then incoming gunfire followed.

Although injured and soaked in fuel from the crash, Cashe dove back into the burning vehicle three times while under enemy fire to rescue trapped soldiers. In the process, his uniform caught on fire, giving him second- and third-degree burns. Despite the burns, Cashe continued to pull soldiers from the vehicle and refused to be placed on the medical evacuation helicopter until all other wounded men had been flown to safety, even though he was the worst injured.

Later in the hospital, when Cashe regained consciousness, his first words were, “How are my boys?” The 35-year-old husband and father died three weeks later. He was posthumously awarded the Silver Star and there is currently a campaign to nominate Cashe for the Medal of Honor.

Melvin Morris

On September 17, 1969, Melvin Morris was commanding the Third Company, Third Battalion of the IV Mobile Strike Force in Vietnam when he led an advance across enemy lines to retrieve a fallen comrade. Morris single-handedly destroyed an enemy force that had pinned his battalion from a series of bunkers and was shot three times as he ran back toward friendly lines with the American casualties, but did not stop until he reached safety.

In 1970, Morris was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for extraordinary heroism during the 1969 battle. After receiving the award, he returned to Vietnam for his second tour. In 2014 he received the Medal of Honor from President Obama, of which he said, “It was an exhilarating feeling, I just can’t describe. But I told myself that now, I’ve got a lot of work ahead of me because I have a message to share.”

In his later years, Morris has dedicated his time to educating young people: “Young children need to know that people are out there putting their lives on the line for them every day … I talk to students and the people about our heritage, about our military, and about why they should learn about history.”

Read more:

3 Great military speeches to inspire you as a leader

Benjamin Davis

Davis received a Silver Star and a Distinguished Flying Cross during his time serving with the Tuskegee Airmen and the Air Force, but what’s most extraordinary is not that he earned those decorations but that they were only a minor part of his many years of dedicated, courageous service. Davis overcame significant obstacles to become a military pilot. He was ostracized as a student at West Point, and when he was commissioned as a second lieutenant, the Army had only two Black officers: Davis and his father.

In his early years of service, Davis fought two enemies: military opponents abroad and rampant racism at home. He once held a news conference at the Pentagon to defend the men of his all-Black military pilot squadron when they were unjustly accused of poor performance. Eventually Davis became the second Black general officer in the Air Force. He left a powerful legacy: In recent years, the U.S. Air Force Academy named an airfield after him and West Point named a barracks after him.

Henry Johnson

Theodore Roosevelt called Henry Johnson one of the “five bravest Americans” in all of World War I, and his actions earned him the nickname “Black Death.” Alone in hand-to-hand combat, he stopped the German army from penetrating the French line of defense in the Argonne forest. The History Channel explains what happened the night of his heroic stand:

Johnson and another private, Needham Roberts of New Jersey, were serving sentry duty on the night of May 4, 1918, when German snipers began firing on them. Johnson began throwing grenades at the approaching Germans; hit by a German grenade, Roberts could only pass more of the small bombs to Johnson to lob at the enemy. When he exhausted his supply of grenades, Johnson began firing his rifle, but it soon jammed when he tried to insert another cartridge. By then the Germans had surrounded the two privates, and Johnson used his rifle as a club until the butt splintered. He saw the Germans attempting to take Roberts prisoner, and charged at them with his only remaining weapon, a bolo knife.

Johnson stabbed one soldier in the stomach and another in the ribs, and was still fighting when more French and American troops arrived on the scene, causing the Germans to retreat. When the reinforcements got there, Johnson fainted from the 21 wounds he had sustained in the one-hour battle. All told, he had killed four Germans and wounded some 10 to 20 more, and prevented them from breaking the French line.

France awarded Johnson the Croix de Guerre with the coveted Gold Palm for extraordinary valor for his immense courage in the face of a formidable enemy. Yet Johnson’s story is a very tragic one. His discharge papers made no mention of his many wounds, so he was considered ineligible for disability pay after the war. His many injuries made it difficult for him to work and support his family. His wife and children left him and he died penniless at just 32 years-old. His story gained attention decades after his death, however, and he was awarded the Medal of Honor posthumously in 2015.

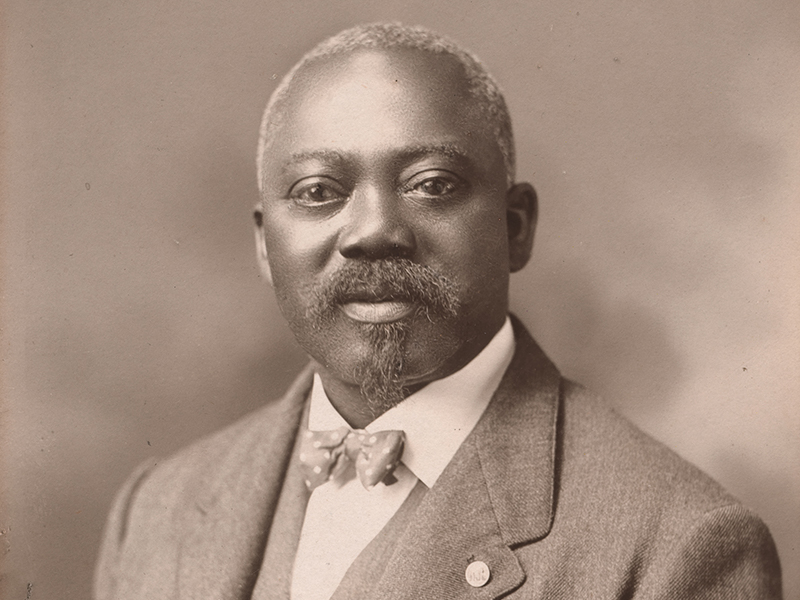

William Harvey Carney

Carney’s story is extraordinary: Born into slavery, he eventually gained his freedom and, as a young man, joined the famed 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry. His heroic actions in 1863 were the first by a Black American to merit the Medal of Honor, although he did not receive the medal until 1900.

To understand the significance of his actions, you have to understand the importance of the flag and its bearer during Civil War battles. The role of color bearer was very dangerous but practically and symbolically critical:

The colors helped soldiers see where their units were located in the confusing, smoke-filled battlefield. Color bearers also set the pace for the march, making sure it was the proper length and cadence. Flags were the centerpieces of the battle, often resulting in high casualty rates of color bearers and their guards. In addition, color bearers didn’t carry weapons, increasing their likeliness of being killed or wounded. If a color bearer happened to be shot down, a member of his guard would immediately pick up the colors in order to avoid the disgrace of losing one.

For Civil War soldiers, it was a matter of great honor to keep their flag flying high, at any cost. So when Confederate bullets struck down his regiment’s color bearer during a charge on Fort Wagner, Sergeant Carney dropped his weapon to lift the colors, even as gunfire felled nearly every soldier around him:

He soon found himself alone, on the fort’s wall, with bodies of dead and wounded comrades all around him. He knelt down to gather himself for action, still firmly holding the flag while bullets and shell fragments peppered the sand around him.

Under an onslaught of enemy bullets, he seized the flag and attempted to rally the regiment, but when it collapsed, he fought his way down a treacherous embankment through seawater, gunfire, and darkness. He was struck by enemy bullets three times, but nothing would induce him to drop the flag.

At last Carney reached the Union rear guard, where a soldier offered to relieve him of the colors. Carney responded that he “would not give them to any man unless he belonged to the 54th regiment.” When Carney finally collapsed at a Union field hospital, badly wounded and exhausted beyond description, he had this to tell his comrades: “Boys, I did my duty; the dear old flag never touched the ground.”