Lenten Campaign 2025

This content is free of charge, as are all our articles.

Support us with a donation that is tax-deductible and enable us to continue to reach millions of readers.

When speaking on the collapse of communism in the 1980s, British historian Timothy Garton Ash noted that St. John Paul II, especially with his 1979 trip to Poland, was a key factor in how those events came to occur. He explained, “Without the Pope, no Solidarity. Without Solidarity, no Gorbachev. Without Gorbachev, no fall of Communism." And yet, had he wished, Mr. Ash could have gone even further back with his domino-effect timeline, because John Paul II's efforts were themselves built upon the earlier works of another. That man would be the recently beatified Cardinal Stefan Wyszyński, the subject of a new film from director Michal Kondrat titled “Prophet.”

Kondrat is mostly known as the driving force behind religious docudramas such as 2019’s “Faustina: Love and Mercy,” however, with “Prophet” he finally ventures into the world of feature film making. In an interview with the Polish newspaper Gazeta Krakowska, Kondrat explained that his desire to make the movie was driven by what he perceived as a general lack of knowledge on the part of most young people in Poland regarding one of the country’s most beloved national heroes. They are somewhat aware of Wyszyński, Kondrat expounded, but they don’t really “know” him.

He hopes “Prophet” will help alleviate that problem by introducing audiences to someone Kondrat describes as a sort of Clint Eastwood in purple robes.

To this end, the movie obviously details the heroic touchstones of Wyszyński’s episcopate such as his “Great Novena” pilgrimage for the Black Madonna of Częstochowa and his celebration of the millennial anniversary of the Christianization of Poland. Wyszyński’s stoic determination in bringing these nationwide events to pass would both humiliate and infuriate Poland’s communist regime. The movie is also sure to include more personal matters, though, such as Wyszyński’s first interactions with a young (and quite studly it would seem) priest named Karol Wojtyła, whom it’s safe to say would go on to do some impressive things himself.

Formative moment

All of that would come later, however. The movie actually begins in 1953 with Wyszyński about to be released from a three-year internment for daring to speak out against the Polish state. On his way home, the newly freed Wyszyński recalls an incident from his time as a chaplain during World War II in which a Polish farmer calmly walks into the middle of a bombardment, tossing seeds as he goes. When the young Wyszyński rushes out to pull the man to safety, the beleaguered farmer states simply, “We need to sow, or only wasteland will remain.” This is portrayed as a formative moment, as it’s a philosophy the Cardinal himself will come to adopt in his decades long struggle against communism.

A good portion of the film is spent documenting the verbal sparring between Wyszyński and Władysław Gomułka, the First Secretary of the Polish United Workers' Party and de-facto leader of Poland for most of Wyszyński’s tenure. As portrayed here, Gomulka is a pure villain so militant in his atheism that he cannot even bring himself to address Wyszyński by any of his clerical titles, instead referring to him only as a director of the Church. Communists do so love to try and control the language, don’t they?

When not concentrating on the ongoing mental chess match between Wyszyński and Gomulka, the film follows the Cardinal’s pastoral relationships with a small group of laypeople. These include Kazia, a young girl he mentors after she is caught stealing food, and Magda, a schoolteacher he regularly counsels. It is through Magda’s filmmaker husband Janek we ultimately learn the source of the film’s title. In need of money, Janek is conscripted by Gomułka to spy on the Cardinal as part of “Prophet,” a secret surveillance operation designed to uncover any evidence the government can use to charge Wyszyński with treason. These efforts to entrap Wyszyński will eventually bring much suffering to those around the Cardinal, Kazia in particular.

The Eight

Most interesting amongst Wyszyński’s acquaintances are “The Eight,” the small cadre of women who run most of the parish’s day to day operations including its publishing office, where the ladies are not averse to printing dissident pamphlets on the sly to aid Poland’s underground resistance movement. It’s always amusing in the movie anytime the Cardinal is faced with a predicament only to order his aide to summon The Eight to handle the situation. It’s almost enough to make one wish for a more fantastical, unrealistic version of the film in which The Eight carry out secret Charlie’s Angels style missions for the Church whenever the need arises.

That’s for another type of film, though. True to his documentarian roots, Kondrat is primarily interested in presenting a respectful and factual story with “Prophet.” Overall, the film plays as a mostly straightforward telling of the events, though there are occasional directorial flourishes, particularly in the scenes surrounding the violence which erupts during the protests of 1970. With this approach, the film accomplishes what Kondrat set out to do, which is to act as a fine introduction to the man who shepherded Poland through decades of communist rule, protecting the country’s spiritual underpinnings and setting the stage for Pope John Paul II’s eventual triumph.

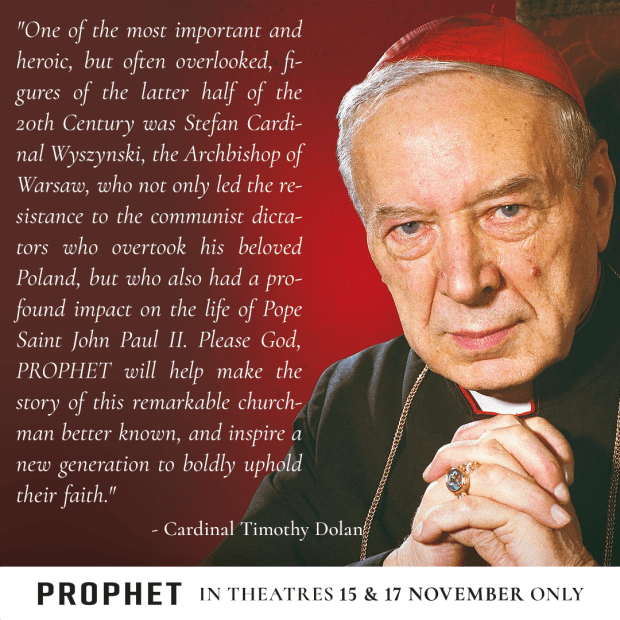

“Prophet” is showing in select theaters on November 15 and November 17.

~

This article is sponsored by Prophet.