Lenten Campaign 2025

This content is free of charge, as are all our articles.

Support us with a donation that is tax-deductible and enable us to continue to reach millions of readers.

Science is central to modern life. It is because of science that you are reading Aleteia on a screen, via the internet, not on paper, by the light of an oil lamp. This series of articles (click here for the whole series) dives deep into the story of the Catholic Church and science. The story goes back a long way. It is still unfolding today. It is not the story you might think you know. But it is a story you should know, exactly because science is so central to modern life.

~

Why would the Vatican ever decide to meddle in a scientific question? We’ve just seen the imperfection of the Church’s processes for evaluating science (see Part 2 in this series). Isn’t science, by contrast, one of the best ways we have for knowing things? It is self-correcting, always bringing us a truer picture of the universe. Science makes the modern world. Science works.

Besides, the ancient matter of Genesis and the “two great lights” is a template for addressing faith-science conflict: the Bible speaks to common understanding, to how the average person might see things; it does not give us a scientific description of the universe. That has been known since St. Augustine’s time (see Part 1).

So why wouldn’t the Vatican just mind its own business?

Well, it gets complicated. And offensive.

A scientific blunder

Scholars have looked at what was taking place in the later 19th century when the evolution question was being discussed within the Church in general, and the Vatican in particular. They have found that various learned people within the Church were emphasizing the importance of the descent of all people from Adam, and the unity of humankind: a provincial council; a bishop; Jesuit critics of evolution; and a Pontifical Biblical Commission.

For example, in 1898 Bishop John Cuthbert Hedley of Newport, Wales, wrote a review of four works by of Fr. John Zahm, CSC, a priest and scientist from the University of Notre Dame in the United States who wrote on evolution. In this review, Bishop Cuthbert stated that “there are some matters so clearly revealed as to be out of the field of question or investigation.” A bishop was arguing that science had no business studying some things!

What sort of things? “The unity of the human race,” was one such thing, the bishop wrote, “as Dr. Zahm himself admits.” This unity, Bishop Hedley thought, was one of several subjects, “in which it would be not only a mistake, but also an offence against religious faith, not to start with a firm hold of what is taught by the Church.”

As another example, a 1909 Pontifical Biblical Commission did not reject evolution itself, but was concerned about Genesis in terms of the origins of the human race. The commission was concerned about humanity’s “monogenistic” origin, such that humanity comprised a single, united family.

The Bible is clearly “monogenistic.” All human beings are descendants of the same parents, Adam and Eve. We are thus all of one family.

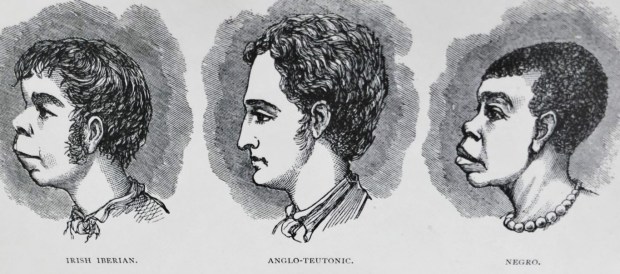

A competing idea, however, was that different “types” of people had separate origins. Under this idea there were, supposedly, actually different species of human (-like) creatures, with these different species commonly being called “races.” This idea is “polygenism” — multiple origins for the multiple human “types” or “races,” with most “races” not being of the line of Adam and Eve.

Polygenism was an ancient idea. It had been bolstered in European minds by voyages of discovery that revealed distant, peopled lands. Polygenism was also considered to be very much heretical.

A martyr of science?

Giordano Bruno is famous for having been burned at the stake in 1600 as an unrepentant heretic. He advocated many ideas that his contemporaries found offensive. Because he also advocated for the idea of an infinite universe of other suns, all of which were circled by inhabited worlds like Earth, he is sometimes considered a martyr for science.

It is a matter of debate among scholars how much his ideas about the universe played in his burning versus, for example, his denial of Christ’s divinity. But one Bruno idea that would offend many today was his polygenism. He argued in 1591 that the different “races” could not all have a common origin:

For of many colors

Are the species of men, and the black race

Of the Ethiopians, and the yellow offspring of America ...

Cannot be traced to the same descent, nor are they sprung

From the generative force of a single progenitor.

Bruno noted that “it is said in the prophets ... that all races of men are to be traced to one first father,” but added that “no one of sound judgement can refer the Ethiopian race to that protoplast.”

Bruno’s singling out “Ethiopians” was typical. It seems it was usually the “black race” that “sound judgement” supposedly indicated was most removed from “true” humans.

Where was science?

Some argued that sound judgement, and indeed science, stood against polygenism. In 1680 Morgan Godwyn published a book called The Negro’s & Indians Advocate, Suing for their Admission into the Church. In it, he noted that different species do not beget fertile offspring. A horse and an ass, for example, can beget offspring, namely a mule, but that offspring is sterile. Godwyn wrote that, if different races were different species like horses and asses, then the people of mixed race, “must, like the Mules... be for ever Barren.” They could not procreate. But, Godwyn said, the contrary is seen daily. “Mixed race” people certainly have children. Thus, humans are of one family, whatever “race” they may be. That was just a fact of science. (Godwyn also noted that Catholic missionaries recognized the unity of humankind, and would even portray Jesus as black.)

Polygenists claimed science anyway. For example, J. H. Van Evrie (M.D.) in his 1861 book Negroes and Negro “Slavery” claimed that “the inference ... that whites and negroes were of the same species, because the mulatto, unlike the mule, did reproduce itself, is simply absurd.” Van Evrie argued that people of mixed race were absolutely sterile — the sterility simply showed up over several generations. This was common knowledge among those who dealt in the slave trade, he said.

Van Evrie was not alone in his ideas. The 1850 meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science featured discussion of how the “types” of human beings were fixed, because “hybrids” were sterile in the long term, and thus died out. The science of polygenism was central to the whole business of racial slavery and oppression. As Van Evrie himself noted,

If the Negro had descended from the same parentage, or, except in color merely, was the same being as ourselves.... then it would be [a Christian’s] first and most imperative duty... to set an example to others, to labor night and day to elevate this (in that case) wronged and outraged race—indeed, to suffer every personal inconvenience, even martyrdom itself in the performance of a duty so obvious and necessary.

This sentiment was not limited to Americans tied up with the question of slavery. Others argued that traditional religious ideas about the unity of and nature of human beings should yield to scientific evidence that showed that there were different species of human (-like) beings. Georges Pouchet of the Muséum national d'Histoire naturelle in Paris complained of how, despite the battles “fought and won” by science against religion in astronomy (about Earth’s motion) and geology (about Earth’s age), “man is a sacred, and, therefore, a forbidden subject.” We can study rocks, but not humankind, he groused. Religion treats facts with derision, he said. You can talk about bears and elephants however you want, “but an Esquimaux and a European, a Negro and a Persian, were to be invariably treated as of one species.” “The true man” was “the large-brained and small-mouthed Caucasian.” Others urged that religious ideas

should succumb to the clear demonstrations of inductive science, and racial facts be championed to their appropriate place, as among the most important and reliable data upon which history, more especially that of the earlier ages, can be based.

Of course, today ugly ideas such as these are not part of science. Modern science is essentially monogenistic; it says that all people are of the same family, and that “racial” variations are quite minor, compared to the variations between individuals, and compared to variations found within other species. The “scientific racism” ideas promoted by Van Evrie and Pouchet have been so thoroughly rejected that today you hear them called “pseudo” science, even though they were science in the 19th century.

Today it is considered (to paraphrase Bishop Hedley) not only mistaken, but offensive, not to start any scientific investigation with a firm hold of the idea that all human beings, regardless of their “race,” are of the same family, and fundamentally equal. Any scientist today who proposed a new polygenistic theory for the origin of human beings, asserting that certain types of people are not truly of the human family, would be roundly condemned.

"Eventually .... "

Today we simply reject the idea that science can tell us that the man or woman standing next to us is not fully human. Those who do not reject it are ranked among the least pleasant kinds of crackpots. Some matters are considered to be so clear (again paraphrasing Bishop Hedley) as to be out of the field of question or investigation.

Therefore, because evolution and polygenism and the idea that certain people were not fully human were all linked together in the 19th century, even those today who care little for the Catholic Church might understand why the Vatican would decide to meddle in the evolution question. Even people today who have little interest in discussions of original sin and salvation history might understand why the unity of humankind must be sacrosanct.

The example of “scientific racism” urges that science be subject to confrontation and criticism from outside of science. The fact that science is eventually self-correcting, eventually brings us a truer picture of the universe, and eventually works is not good enough when science can go so far wrong, in such a consequential manner.

~

This series is based on the paper “The Vatican and the Fallibility of Science,” presented by Christopher M. Graney at the “Unity & Disunity in Science” conference at the University of Notre Dame, April 4-6, 2024. The paper, which is available through ArXiv (click here), contains details and references for the interested reader.

The paper, and this Aleteia series, expands on ideas developed by Graney and Vatican Observatory Director Br. Guy Consolmagno, S.J. in their 2023 book, published by Paulist Press, When Science Goes Wrong: The Desire and Search for Truth (click here).