Lenten Campaign 2025

This content is free of charge, as are all our articles.

Support us with a donation that is tax-deductible and enable us to continue to reach millions of readers.

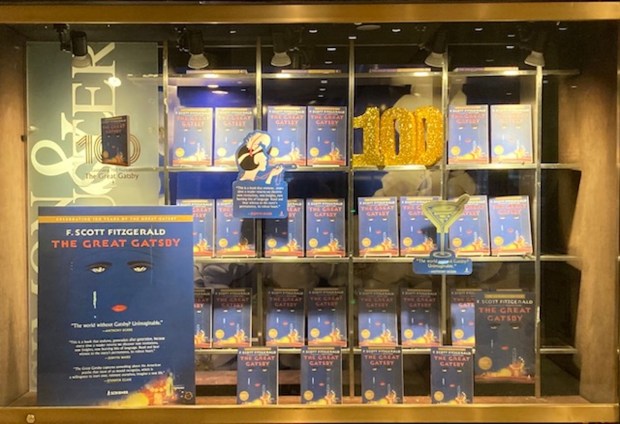

When The Great Gatsby was published 100 years ago today by Charles Scribner’s Sons, few could have known the impact it would have on the American scene and psyche.

“It’s the most important American novel of the 20th century,” American writer, Jay McInerney said. “It’s the great American novel. That illusive notion of the American dream has never seemed quite so tangible as it is in the context of The Great Gatsby.”

Its author, F. Scott Fitzgerald, was dazzled by great wealth and those who possessed it. But, in the end, it all proved illusive. Meanwhile he eschewed the spiritual gold of his Catholic faith into which he was born — a faith his friend Hemingway had, ironically, converted to.

As Morley Callaghan related in his memoir, That Summer in Paris, when they visited Saint-Sulpice, Scott, who lived nearby, always conscious of the big looming church, nearly the size of stately Notre-Dame Cathedral, demurred when Callaghan motioned to step inside. “Don’t ask me about it. It’s personal,” he told him. “The Irish-Catholic background and all that.”

He was raised in the faith, perhaps too strictly, and his artist’s heart missed the essence of the faith that enlightened Hemingway’s writing.

Yet, Scott always held the Church in a place of reverence, marrying his Jazz Age sweetheart, Zelda Sayre, at St. Patrick’s Cathedral shortly after his hit This Side of Paradise was published on March 26, 1920, also by Charles Scribner’s Sons.

Buried

Scott’s life ended much too young in December 1940. He was in Hollywood writing scripts, making $1 million a year, (albeit none were produced); and writing his final novel The Last Tycoon, based on the life of MGM production head, Irving Thalberg.

He drank like a fish and spent money almost as fast as it came in, given his many financial responsibilities: Zelda was now living in an Asheville, North Carolina, sanitarium and their daughter Scottie was attending Vassar.

Zelda insisted that he be buried at Old St. Mary’s in Rockville, Maryland, with the rest of his family, but the church would not allow it since he had not gone to Confession nor received Holy Communion regularly, the parish priest told Scott’s Princeton roommate John Biggs. So, he was buried at nearby Rockville Cemetery.

By 1975, the cemetery was looking quite shabby, and Scottie, then living in Georgetown, approached the Washington Archdiocese once again for permission to bury her father in the family plot. This time, it was granted.

Archbishop William Baum reasoned that Scott was “an artist who was able with lucidity and poetic imagination to portray the struggle between grace and death. ... His characters are involved in this great drama, seeking God and seeking grace.”

Just so. For, in portraying that illusive quest for what is fleeting, Fitzgerald shone a light on the more satisfying quest for God and his grace.

As he famously wrote in the words of narrator Nick Carraway –

… gradually I became aware of the old island here that flowered once for Dutch sailors’ eyes… (and) for a transitory enchanted moment man must have held his breath in the presence of this continent, compelled into aesthetic contemplation he neither understood nor desired, face to face for the last time in history with something commensurate to his capacity for wonder…

Gatsby’s “wonder” and unrealized “dream … was already behind him,” said Nick, who soul-searingly ended with these iconic words –

Gatsby believed in the green light, the orgastic future that year by year recedes before us. It eluded us then, but that’s no matter — tomorrow we will run faster, stretch out our arms farther . . . and, one fine morning—— so we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.

The last 14 words etched on Scott’s tomb ledger.