The credit often went to men, but here’s the full truth.

Lenten Campaign 2025

This content is free of charge, as are all our articles.

Support us with a donation that is tax-deductible and enable us to continue to reach millions of readers.

Women are responsible for discovering or inventing many things that advance our knowledge of the world and our ability to live in it. Women don’t always get all — or any! — of the credit they deserve, however. Here are 5 contributions by women to celebrate.

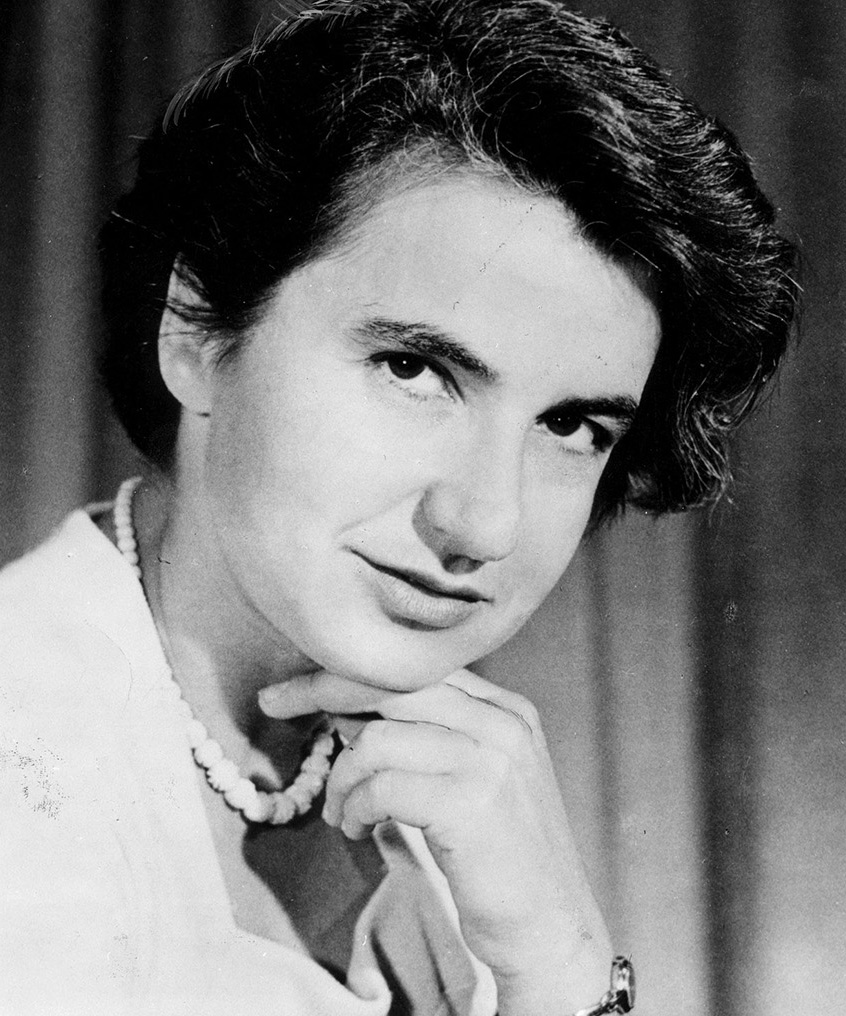

1. The Structure of DNA

James Watson and Francis Crick revolutionized the scientific world when they published an article about the double-helix structure of DNA, but they forgot to mention the help of their female colleague, Rosalind Franklin.

She was the one who managed to take DNA images by X-ray diffraction. And another scientist, Maurice Wilkins (with whom Franklin had apparently had some differences in the past) took her innovative images to Watson and Crick so they could do their research. The three of them shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine in 1962 and, although Watson said that Franklin should have won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry along with Wilkins, it just didn’t happen. She then devoted herself to conducting outstanding research on the molecular structure of viruses.

2. The paper bag machine

Okay, maybe it’s not the most technological or sophisticated invention, but think about how many sandwiches and breads have been stored in this type of bag. In addition, its inventor, Margaret Knight, had to fight to get credit for it.

Knight made a prototype machine out of wood, but in order to get the patent, she had to make it out of metal. So she took her design plans to a factory, where a man named Charles Annan stole them and patented them as his own, claiming that it was impossible for a woman to have created such a machine.

Knight did not hesitate to bring him to trial and, although it took three years, she won the case, founded her own company, and obtained all the royalties.

3. Computer programming

Ada Lovelace’s mother encouraged her daughter to study mathematics for her professional development without knowing that she would go on to become a pioneer in computing. At age 20, Lovelace began working with inventor Charles Babbage and they came up with the idea of creating an “analytical machine.”

In her notes, we can find what is now considered the first algorithm for machine processing: a series of step-by-step instructions for solving problems. Although several say that she was the one who opened the way for computers as we know them today, most people say Charles Babbage was the real author.

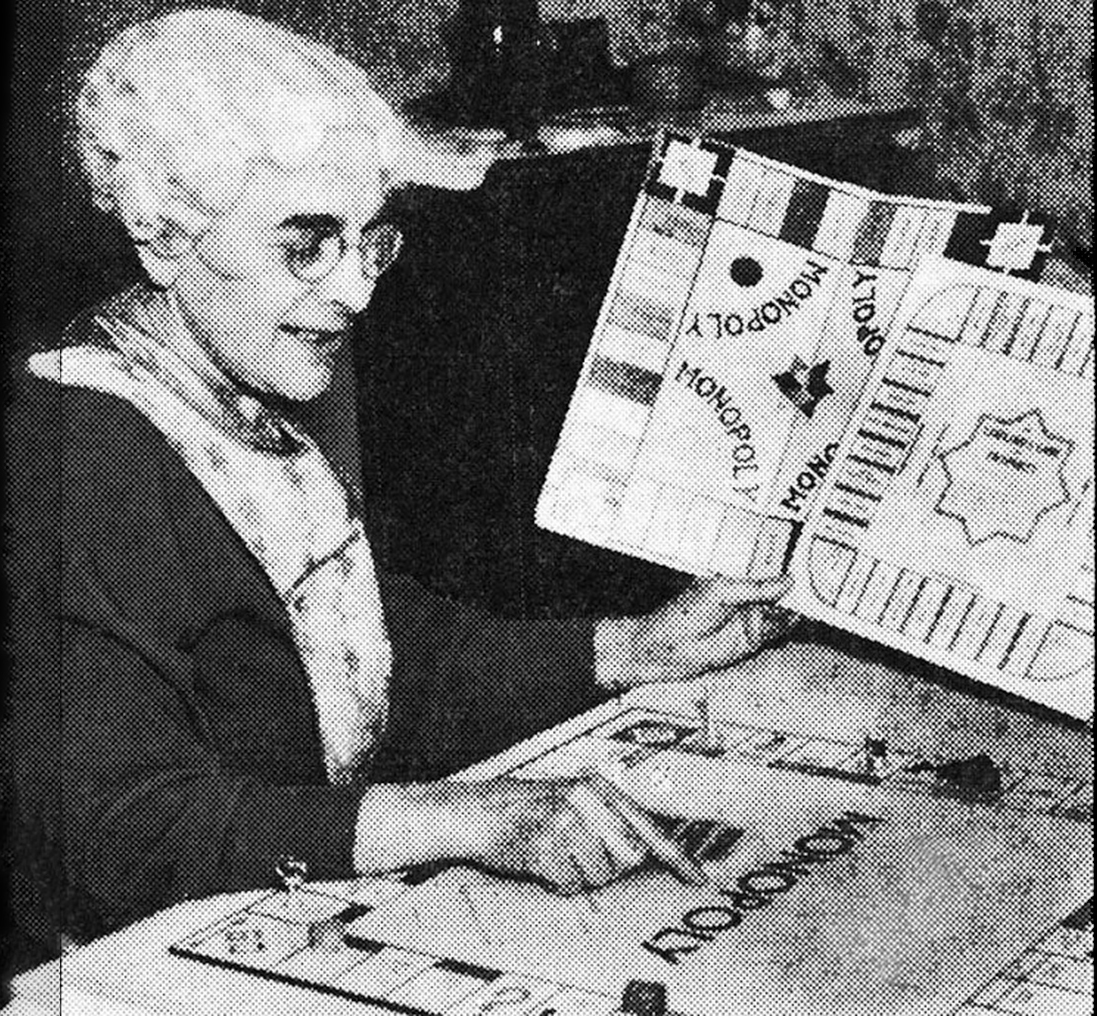

4. Monopoly

Elizabeth Magie (or “Lizzie” J. Philips, after her marriage) decided to create a board game called “The Landlord’s Game” to teach what happens when a few people hoard all the land. She patented it in 1904 and it soon became popular.

Years later, several replicas were made with some variations on the theme, but the entrepreneur Charles Darrow was the one who really took advantage of changing the board without giving Magie’s original idea any credit. He patented it again under the title of “Monopoly” and became a millionaire on royalties after selling the rights to a major American toy company.

Then another company created the Anti-Monopoly game, and of course was sued. However, that lawsuit revealed that the Monopoly game was not actually an original creation, and Elizabeth got her recognition. The spirit of her game was lost, however, since in Monopoly the winner is the one who has the most properties.

5. Circular saw

Sara “Tabitha” Babbitt was a weaver who was part of the Harvard Shaker community, where the communal good was valued over individual achievement, especially for women.

Around 1810, Babbitt observed two men cutting wood with a traditional saw and realized that it was a waste of time and energy because the saw cut only when it moved forward, but not backwards.

Three years later, she created a circular saw model, and her entire community thanked her for making their jobs much easier. But she did not patent her invention because of the community’s beliefs.

Sadly, a few years later, three men learned of her invention and patented it as their own.

This article was originally published in the Spanish edition of Aleteia and has been translated and/or adapted here for English speaking readers.