Lenten Campaign 2025

This content is free of charge, as are all our articles.

Support us with a donation that is tax-deductible and enable us to continue to reach millions of readers.

Much of what we know about Jesus’ looks is a product of artistic convention. Since Scripture does not provide a description of what Christ looked like, so painters and mosaic-makers would often resort to the artistic canons of their time to create a visual image of the Nazarene.

This means that some of the earliest depictions of Jesus offer a precious insight into the diverse iconography style of the places and people that made up early Christianity.

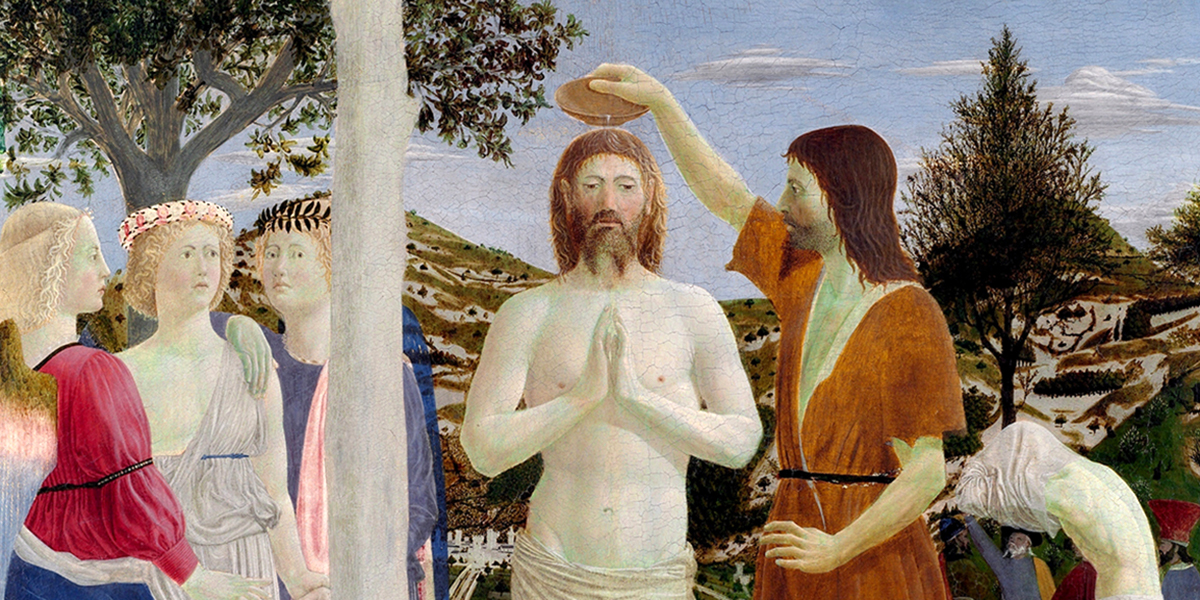

Most likely, the robe-wearing, European-looking Jesus image we are familiar with can be traced back to the Byzantine period, when artists had to make choices on how to represent the Son of God. As explained by Joan Taylor, a Professor of Christian Origins and Second Temple Judaism at King’s College London, those representations of Christ "were probably inspired by existing godly figures like Zeus and Apollo.”

That would explain, for instance, why Jesus got a Zeus-like haircut —long-hair and a beard— and Apollo-like features —a slim body and delicate lineaments. The Byzantine era is also when Jesus starts to be depicted with a royal robe, as opposed to the simple tunic that he most likely used to wear. In fact, many of the symbols and visual arrangements used to convey the “authoritative” aspect of Christ as Pantocrator are drawn from classical and imperial iconography.

But if representing Jesus is difficult, representing the Father was even harder. For centuries, Christian iconography would abstain from doing so, not giving the Father an anthropomorphic shape and using different symbols and allegories to represent the Creator.

In fact, during the first thousand years of Christianity, and in obedience to interpretations of specific Bible passages, pictorial depictions of God the Father had been avoided by Western Christian artists. At first, only the Hand of God (often emerging from a cloud) was portrayed, as if suggesting divine intervention. It was only by the time of the Renaissance when artistic representations of God the Father were freely used.

But of the three persons of the Blessed Trinity, the Holy Spirit is often the most difficult to depict in art. Representing its action in Scripture is also not an easy task. Attempts to do so have ranged from painting three nearly identical figures that represent the three persons of the Holy Trinity (an image that was later explicitly forbidden by Pope Urban VIII), from a dove, to a flame, depending on the passage of the Scripture the artist is drawing inspiration from.

There is more to the Holy Spirit in Western art and the Bible than doves and flames. Visit the slideshow below to discover 8 symbols of the Holy Spirit both in art and in the Bible, as described by the Catechism of the Catholic Church.