A brief look at some aspects of the Western history of the notion of beauty might explain some of the key features of demonic iconography.

Lenten Campaign 2025

This content is free of charge, as are all our articles.

Support us with a donation that is tax-deductible and enable us to continue to reach millions of readers.

Since its very inception, Christianity has believed it is possible to know God, as the origin and telos of the universe, from the contemplation of movement, order, and beauty in nature: “Since the creation of the world,” Paul writes, “God’s invisible qualities—his eternal power and divine nature—have been clearly seen, being understood from what has been made” (Rm 1:19-20).

Any possible perfection found in a creature is but a reflection of the infinite perfection of God, “for from the greatness and beauty of created things comes a corresponding perception of their Creator.” (Wisdom 13:5). However, it is also true that God transcends every creature, and it is necessary not to conflate God and Creation, or God and any representation we can make of him, since the images that refer to the greatest mysteries of faith (may these be pictures, diagrams, even ideas) fail to completely exceed the order of sensible things. God Himself, some of the great voices of the tradition have pointed out, would somehow be “the great iconoclast.” The ways in which divinity is represented will always need to rely on references to what is highest in creatures, yet only metaphorically, figuratively.

In Chapter 46 of his First Apology, St. Justin (ca. 100-165) explained:

“We have been taught that Christ is the first-born of God, and we have declared above that He is the Word of whom every race of men were partakers; and those who lived reasonably are Christians, even though they have been thought atheists; as, among the Greeks, Socrates and Heraclitus, and men like them; and among the barbarians, Abraham, and Ananias, and Azarias, and Misael, and Elias, and many others whose actions and names we now decline to recount, because we know it would be tedious.”

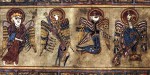

Like many of the Fathers, Justin favored and encouraged the communion of Christianity with classical Antiquity. Following this tradition, the Christian Middle Ages feed on both the most heroic and noble images inherited from its Greco-Roman past and the rich diversity of its mythical world, populated by beings with heterogeneous, zoo-antropomorphic bodies. But, as the anthropologist and art historian Vladimir Acosta noted in his Prodigious Humanity, “when medieval art goes through a ‘classical’ period, it looks for the fundamentals of a harmony […] in the periods in which this stability is altered […] we find the monster and the beast again.” It is in this alternation between harmony and the monstrous that we find one of the sources from which the representations of Hell and demons arise, bringing in the images of deformed and fabulous beings compiled in bestiaries, used as decoration in sculptures, tapestries and miniatures, and illustrating the margins and capital letters of Gothic manuscripts.

Read more:

Dragons, unicorns, cynocephali: the favorite monsters of the Middle Ages

The more or less medieval conception of the world as a battlefield between virtue and sin, which circulated especially in monasteries and eremitic and ascetic circles, favored the appearance of many purposely horrendous figures, able to synthesize evil in an image. As is well known, the Christian constantly fights against the onslaughts of the evil one. In fact, in the lives of ascetic saints and the Desert Fathers, demons arise everywhere, not only as animal and monstrous figures, but also as radiant angels or disguised as beautiful women. But whereas beauty is considered a positive attribute, taking pride in beauty itself is not consistent with the principles of spiritual beauty. From the reading of the book of Ezekiel (Ez 28:11-19) in which the fall of the king of Tyre is narrated, exegesis finds an image of one who would have been the most beautiful and radiant angel in Heaven right when he became the fallen one:

You were the seal of perfection, full of wisdom and perfect in beauty. You were in Eden, the garden of God; every precious stone adorned you (…) You were anointed as a guardian cherub, for so I ordained you. You were on the holy mount of God (…) You were blameless in your ways from the day you were created till wickedness was found in you. Through your widespread trade you were filled with violence, and you sinned. So I drove you in disgrace from the mount of God, and I expelled you, guardian cherub, from among the fiery stones. Your heart became proud on account of your beauty, and you corrupted your wisdom because of your splendor. So I threw you to the earth (…) By your many sins and dishonest trade you have desecrated your sanctuaries. So I made a fire come out from you, and it consumed you, and I reduced you to ashes on the ground in the sight of all who were watching. All the nations who knew you are appalled at you; you have come to a horrible end and will be no more.

Through this asymmetry, demonic iconography can be easily drawn. Initially, demons would be represented like any other angel, but in a different color: either green, black, or livid, as if dead. The Byzantine model of the devil is that of a small, dark, hairy, agile and mocking figure that had already been also used to represent wild, pagan, monstrous legendary peoples. In fact, the destruction of the monstrous is also understood as a consequence of Christian preaching (as in the case of St. Christopher, and several apocryphal stories of the life of the apostles Peter and Paul).

Read more:

What does Satan really look like?

But the image of evil as a being composed of anthropomorphic and animal combinations is not only Greek heritage. One also finds this kind of creatures in ancient Persian and Egyptian religions. Moreover, Persian creatures are supposed to be the origin not only of the multi-headed beasts of the book of Revelation and the Byzantine dragon, but also of some of the images found in the Book of Ezekiel (which makes sense, considering the prophet lived during the Babylonian Captivity period).

Read more:

Ox, eagle, lion, man: Why and how are the Evangelists associated with these creatures?

It is only later, mostly after the 9th century, when the devil assumes human forms, but with many zoomorphic features: lacking feet or hands, he has hooves and claws instead. His back ends in a reptile tail (surely a remaining trace from the early days in which he was represented as a snake or a dragon). But an important and often overlooked novelty also appears in this period, which has an interesting and unique moral teaching: the devil’s joints are usually crowned with monstrous and deformed faces, if not with fierce animals. These faces are often repeated in the chest, in the groin and in the back. This is a particularly curious way of implying that the creature’s higher powers (those of the mind, located symbolically in the head) have been put to the service of lower appetites and impulses; the isthmus of the neck, which separates the brain from the other organs, has suddenly disappeared! For this reason, it is also common to see Satan represented as a “gastrocephalic” being, with a single face occupying his entire trunk.