Einstein called Lise Meitner “our Marie Curie.”

Help Aleteia continue its mission by making a tax-deductible donation. In this way, Aleteia’s future will be yours as well.

*Your donation is tax deductible!

Lise Meitner was born in Austria in November 1878 in the heart of a Jewish family. She entered the University of Vienna in 1901 to study physics and earned her doctorate five years later, a great achievement considering that academia didn’t want to accept women at that time.

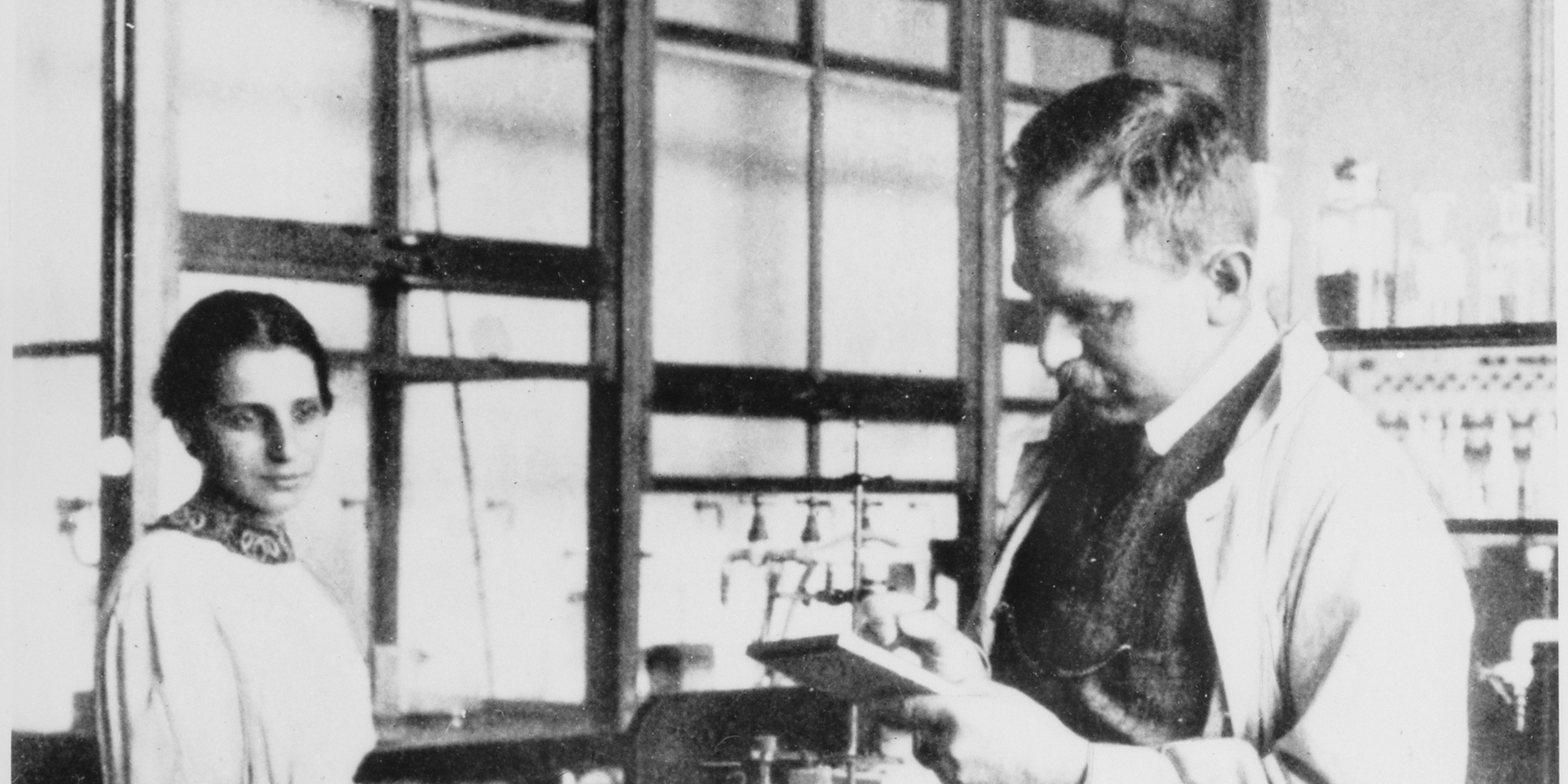

Degree in hand, she decided to go to Berlin to look for greater opportunities and to continue learning from the chemist Otto Hahn, with whom she began a research project on radioactivity that would continue for almost 30 years.

Putting their physics and chemistry expertise together, Meitner and Hahn discovered protactinium, a kind of metal, in 1918. Five years later, Meitner also discovered a “physical phenomenon in which the disappearance of an internal electron within an atom causes the emission of a second electron,” but a man, the French scientist Pierre Victor Auger, received the credit. He supposedly “discovered” the same thing two years later (there is no proof of plagiarism). His discovery was published in a more famous and influential review.

In 1938, under the pressure of the Nazi persecution of the Jews, Meitner left Germany for Sweden, where she continued her atomic research at the Manne Siegbahn Institute at the University of Stockholm with the few resources her father was able to give her. Months later, she was able to meet clandestinely with Hahn in Copenhagen (they had corresponded by letter all this time), and they planned a series of new experiments that finally led to the first example of nuclear fission.

Hahn published these results (the experiments were done in his laboratory) and then Meitner, along with the German chemist Fritz Strassmann, did the physical demonstration, also introducing the term “nuclear fission.”

Other scientists notified Albert Einstein (who referred to Meitner as “our Marie Curie”) about the experiment, and that was when he decided to write that famous letter about the new discovery to President Franklin D. Roosevelt — a letter he later regretted having written, since it led to the creation of the Manhattan Project, which was the effort to build an atomic bomb before the Nazis and the Soviets could.

Otto Hahn received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1944 for “his” discovery of nuclear fission and Meitner was completely ignored as the co-author. Some said it was an “understandable error” because, as a Jew, Meitner often had to be in the background. Others say her name was sufficiently well known in scientific circles and that it had more to do with her gender.

More than 20 years had to go by for Lise Meitner to be granted the Enrico Fermi Prize (a recognition granted in the physics world) in the United States in 1966 along with her colleagues, Strassmann and Hahn.

She was received with extended applause and they referred to her as “the woman who left Germany with the bomb in her wallet.” This was not a reference Meitner appreciated, as she was the only scientist (male or female) who declined to participate in the Manhattan Project, since she didn’t want to be part of the creation of a bomb.

In the end, she retired to live in England, where she died in 1968, remaining the most important woman scientist of the 20th century. In 1992, they even decided to name the heaviest element in the universe after her, calling element 109 “Meitnerium.”

On her tombstone, her nephew had this epitaph inscribed: “Lise Meitner: a physicist who never lost her humanity.”

Read more:

New study finds the missing link between women and science

Read more:

Fusion may be the future of energy

This article was originally published in the Spanish edition of Aleteia and has been translated and/or adapted here for English speaking readers.