Signatures might be important, but they are not essential. Even today.

Lenten Campaign 2025

This content is free of charge, as are all our articles.

Support us with a donation that is tax-deductible and enable us to continue to reach millions of readers.

Signing a work of art might be understood as a gesture implying the recognition of individual creativity. But in fact, particularly relevant, unique works of art rarely need to be signed by the artist, as the distinctive style and use of visual expressive elements are often more than enough to identify the author of a specific work. People with little-to-average knowledge of history of art might recognize a Rothko, a Dürer, or an El Greco without needing to look at the artist’s signature, or the small info panel the museum curators have had the kindness to place right next to, or under, the piece we are looking at. But can we say the same thing about medieval sculptors, painters, the exceptional embroidery artists responsible for the famous Unicorn Tapestries, or the architects who designed all the great Romanesque basilicas of the Early Middle Ages? Can we name a single sculptor from, let’s say, the 8th century? It is often the case we know more about the emperors, popes, bishops, or abbots who commissioned such works than about the artists who actually made them. Why is that so?

Signatures might be important, but they are not essential. For art connoisseurs and collectors (that is, professionals who have an educated eye), most of the time everything they need is already in the work itself. A signature is just another element that must be considered when identifying, dating, and valuing a piece of art. But fake signatures (that is, falsifications) have also proven to be not only the stuff some movies are made of, but also relatively abundant. However, even specialists in medieval art might only be able to identify where and when was the piece made, not by whom.

Ancient Greek ceramists, for instance, would sign their works with an interesting twist: they would have their clay vases “speak” about their authors. Painters and potters were usually, but not always, separate specialists (“kosmetai” and “kerameus” respectively). It is not uncommon to find some Greek vases with the inscription “(name of the artist) made me.” That is how the names of Ergotimos, Kleitas, and some other ancient Greek ceramists are still known to us. We know the names of Polykleitus, Myron, Praxiteles, and Phidias, the great Greek sculptors and architects, thanks to various ancient sources (including Xenocrates’ 4th-century catalogue, but also Plato, Pausanias, and even Cicero). But that doesn’t seem to be the case with medieval artists at all.

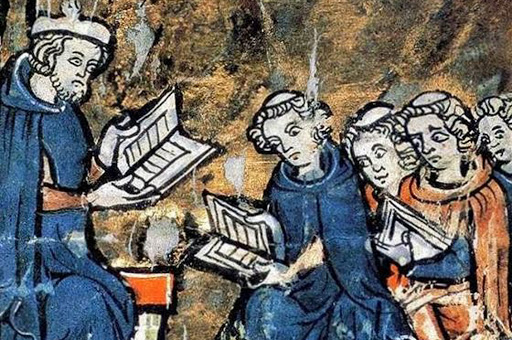

Specialists give different explanations for the almost absolute lack of signatures in medieval art. Some historians argue the reason signatures began to reappear in art during the early Renaissance is related to a “production shift.” Medieval art was mainly produced by co-operative guild systems. The development of these guilds implied a crucial stage in the professional development of artists, which would eventually lead to the Renaissance’s recognition of artistic genius as being exceptional — although Renaissance and Baroque artists continued working in workshops, often under the supervision of an already known “master.” (For instance, Leonardo was educated in Maestro Verrocchio’s workshop, not too differently from how an apprentice would learn the trade in one of these medieval guilds.) How could a collective “sign” a cathedral?

Now, unlike singled-out Renaissance artists, who would be well-paid and recognized for their individual work (whether they signed it or not), medieval artists worked collectively. Cloth makers, shoemakers, apothecaries, masons, painters, sculptors, and basically all kinds of craftsmen would join guilds not only controlling the production of all kinds of goods, but also defining the standards of their own particular craft. Of course, as new sources of wealth began to appear (rich Italian merchant families would be key in this process), it is only natural artists would rather sign their works so they could get recognition from different potential customers (and not only the nobility, or the church) and, consequently, more contracts.

Some other scholars attribute a more “spiritual” approach to this medieval anonymity, arguing only the work of art itself, and not the artist, was important. Given the fact that most (if not all) of these artworks were indeed religious, a distinctive sense of humility (when not laymen associated in a guild, most artists would be monks) would keep the artist from signing the work. Since most of these pieces would be used for liturgical, contemplative, or devotional purposes, it would seem wrong for the artist’s name to be included in the image. However, genuinely pious artistic geniuses such as Michelangelo (who was a Tertiary Franciscan), Velásquez (who was a knight of the Order of Santiago), and even Fra Angelico (the 115th-century Dominican friar beatified by John Paul II) would not shy away from acknowledging their authorship, whether by signing their pieces or not.

Visit the slideshow below for a summary of this article: