Anyone who has seen Mel Gibson’s film The Passion of the Christ remembers that terrible moment during Jesus’ trial before Pilate when the crowd chooses to free Barabbas instead of Jesus. We look at the bloody, bruised and broken face of Christ, which even in that condition radiates calm, peace, and beauty, and compare it to the vulgar and ugly face of Barabbas, a convicted murderer, full of defiance, vice, and Joker-like mania.

It’s an exaggeration, but it’s highly effective to convey the irrationality of the crowd’s choice. Yet even as Barabbas in the film is freed from his bonds, he meets Jesus’ eyes and stops for a moment, pierced by that gaze, before descending the stairs to the crowd.

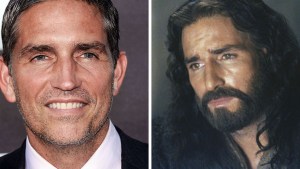

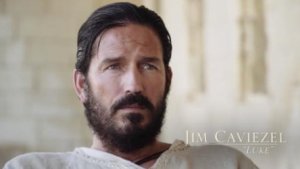

They’re just actors in a scripted scene: Jim Caviezel in the role of Jesus, and Italian actor Pietro Sarubbi in the role of Barabbas (both wearing abundant makeup; Sarubbi is almost unrecognizable when seen outside of that role). But making the film was a transformative experience for both actors. Caviezel’s testimony has been widely shared and discussed, but Sarubbi was just as affected, despite spending just a few minutes on screen.

Here is the testimony of this actor and university professor, as he shared it with Aleteia contributor Annalisa Teggi, who interviewed him:

Today I’m a 58-year-old man. To tell the truth, I should say 59, but I’m not taking this year, 2020, into account because I haven’t really used it. I’m an actor and also a man who tries to live up to the Christian experience I have, and that requires a great effort in this world which is increasingly difficult to understand, and increasingly disenchanted with beauty.

For about 20 years I’ve been teaching Film Craft at the Civica Film School in Milan, which started out as a simple professional training center but which, in the 50 years of its existence, has become—thanks to an excellent program started by Moratti—a university. There’s a three-year degree in Film Craft, and therefore, improperly, I find myself to be a university lecturer with very lively, curious, intelligent and very technically skilled students.

Even though it is a very secular field, for me it’s a small frontier of Christianity because it allows me to put myself to the test and to be at the service of giving that “extra” of beauty and total effectiveness which, in my opinion, Christian teachers possess. It’s that way of looking at people that allows you to see the eyes of Christ in the student who’s not studying, who has problems, or who is irresolute, and this completely changes the relationship. This way of looking doesn’t go unnoticed, even for young people who are far from faith: It disconcerts them when they see beauty where they were told it shouldn’t be.

At the risk of boring those who already know me, I myself was thrown off balance by that look of which I was just speaking, and here I’m referring to my life-altering participation in Mel Gibson’s film The Passion of the Christ. While I was playing Barabbas, the Holy Spirit used one man to look at another man. Now it’s clear to me; it was perturbing and unsettling then.

Later on, I read Benedict XVI’s encyclical “Deus Caritas Est,” in which there’s a phrase that expresses very clearly what had also happened to me: The Lord encounters us ever anew, through the eyes of the men and women who reflect his presence.

This is precisely God’s method: to look at people through the eyes of other people. This explained what was inexplicable to me: I could not imagine that a simple actor playing Jesus could look at me in a way that turned my soul upside-down. From that moment on there was a change in my personal, human, and professional life, because when you’re captivated, you’re captivated in every way.

Read more:

When the Man Who Played Jesus in “The Passion of the Christ” Met John Paul II

I was very struck by a passage written by Bishop Nicola Lepori about St. Peter: “He met Simon and called him Peter, called him with a new name, making him new and leaving him as he was.”

Conversion is exactly that: You’re called to a new name and a new life while remaining who you are. And from that moment on an entirely human challenge begins, because there’s no magic wand that transforms you; you remain exactly who you were, but you fall in love with Christ, and your life becomes an attempt to live up to that love. You remain with your sin and your smallness, but you’re enriched by the hope that through prayer you can walk without fear in a new direction.

This conversion led me to leave the theater, nauseated by the superficiality and pettiness that was there, until a very dear friend from Ravenna told me that I really had to return to the theater and there, within the art, I had to be at work with the new gift that I was carrying within me. So, about 12 years ago I started this adventure of being involved in theater that was beautiful, enjoyable, funny, comic but also deep, and I started with a show about St. Peter.

Later I had the good fortune that the Commission for the Jubilee of Mercy got wind of my work and asked me to do a show for the Jubilee year on the theme of Mercy. After a little while studying and a little while investigating, I realized that St. Joseph was one of the most merciful, patient, and welcoming people, and I dedicated that show to him. Now, so to speak, St. Peter and St. Joseph are my battle horses. I have three new challenges in the pipeline: St. Augustine, Guareschi (the creator of Don Camillo) and St. Philip Neri. My path is that of smiling, and some have accused me in past years of being disrespectful because I speak of Jesus also through the perspective of laughter. I respond to these objections by saying that if we think, really, of 12 normal people like us who meet Jesus, it would not be strange to imagine them laughing, moving around, and jumping. Don Giussani said, “Given what you’ve learned and what you’ve found, you can’t allow yourself to be sad.”

Those who have a strong faith understand the immense value of lightheartedness; those who have a penitential faith, one of pain and not forgiveness, see a smile as something disrespectful. But we are children of a God who is slow to anger and rich in forgiveness, so our prayer is the Our Father. Inside that prayer is found everything about us and about me, because there’s a Father who with enormous affection has given me many kicks and punches. Those who love you are worried about you, and so they come to slap you around.

With my students at school, I try to bring this way of looking that is of God, and I tell them that I’m not supposed to be nice as a teacher, but useful. I don’t have to be a buddy or a companion, but a guardian and a nuisance. They have a little bit of trouble understanding this, but when I meet them on the set after school, they always repeat to me: “Prof, now I understand!” I’m moved when that happens, so to downplay it I answer with the words of St. Augustine: “Late have I loved you …” I mean that God, as Father, spares us nothing, and those who have converted as I have don’t live in a magical bubble where everything is in place. Fatigue is still fatigue, even pain. We’re spared nothing, but God has spared His Son nothing either; why should we insist on asking God, as if it were His duty, to take something away from us?

For me, who tends to talk too much, it’s difficult to condense all this experience that I’ve told you about into a single word. I’ve thought about it and I think that the right word is docility. I happened to participate in spiritual exercises, and I was even a little bored, and annoyed by all the people who were silent and obedient (I’ve always been a rebel!), and it was right there that I began my journey of docility, when I was struck by how Mary’s docility was presented to us.

Thinking about it, my whole theatrical journey also has this theme in the background: St. Peter was a rough guy; I come from the south of Italy and I met many fishermen like him. He was irascible, ready to get into action, and since he met Jesus he was continually invited to be docile. Peter had a hard time being as Jesus called him to be; St. John Paul II said that God made Jesus choose Peter as the the first Apostle, taking the worst of Capernaum, to give a strong signal to everyone, and to show that holiness was for all. If Saint Peter made it, we too can make it.

St. Peter comes to surrender himself to Jesus with all the surrender of those three “Yeses,” to which he responds to “Do you love me?” And another enormously docile “Yes” is that of St. Joseph. Everyone knows Mary’s “yes,” but few are familiar with Joseph’s “yes,” which is the “Yes” of everyday life, the one he pronounced throughout all the years he lived quietly with Mary and Jesus. His is the “yes” of all those who get up every morning and open themselves to life, prayer, vocation, and work.

Read more:

7 Trials and tribulations that Jim Caviezel faced playing Jesus Christ

Read more:

Jim Caviezel talks about his spiritual preparation for ‘Paul, Apostle of Christ’